We now have the world in our pockets. Our TVs are smart. Our cars soon to be driverless.

We now have the world in our pockets. Our TVs are smart. Our cars soon to be driverless.

We live in the tech futures of 1970s futurists, or at least partly.

Along with predictions of technological development came ideas of utopias and dystopias. The technology we craft creates new use cases, opportunities, and dangers. The tech and its application cannot be separated.

This brings us to larger questions of how we should employ technology, what risks new tech may bring, and what the arrival of these new futures means to us as humans on our little ball of dirt.

This is the sphere of digital ethics.

Process Street was invited to the inaugural World Ethical Data Forum, and it has set our minds rolling over some of these questions and the discussions of what may lie ahead.

In this article, we’ll cover:

- What is digital ethics?

- 3 current hot topics in digital ethics

- 3 challenges discussed at the World Ethical Data Forum

- What to look out for in the future of digital ethics

What is digital ethics?

Digital ethics is the field of study concerned with the way technology is shaping and will shape our political, social, and moral existence.

As Rafael Capurro puts it in his 2009 paper Digital Ethics:

Digital ethics or information ethics in a broader sense deals with the impact of digital Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) on our societies and the environment at large.

Simple enough, no?

Well, yes and no. Investigating moral and political philosophy is difficult at the best of times; consensus is hard to find and even basic premises are disputed.

With digital ethics comes the added variable of assessing the ethical implications of things which may not yet exist, or things which may have impacts we cannot predict.

The sociologist Ulrich Beck’s concept of risk society addresses the growing nature of uncontrollable risks and the increase of uncertainty in the way we construct our understanding of society and questions pertaining to it. This theme seems pertinent in the study of digital ethics as we seek to estimate what impacts different technologies will have on human existence, without ever really knowing for sure.

In this sense, digital ethics can come across as a very unscientific investigation of sometimes very scientific subject matter.

The transferring of consciousness to computers, a world run by robots, and technologically enabled immortality all sound like Asimov-inspired dreaming, yet they look increasingly like plausible future outcomes.

However, not all digital ethics falls in the scope of imagining what the world will look like in 50 years time. We already live in a digital society and we’re already seeing the effects of these new networked technologies on our political, social, and moral spheres.

Are smartphones eating away at our attention spans? Is Instagram making whole generations depressed? Are we living in an era of perma-cyberwarfare?

These are all more grounded and more testable phenomena which we can study and assess.

In this article, we’ll pull out 10 different topics in digital ethics and give a quick overview of the debates and challenges relating to them. Some sci-fi, some realpolitik.

3 current hot topics in digital ethics

Let’s start off with a couple of large discussions within the scope of digital ethics just to warm up!

Is code speech? How should it be legislated?

At the heart of our technological revolution is a new means of communication.

This mode of communication allows humans to talk to computers, and computers to talk to each other.

This is computer code. The same thing which powers this website, the Process Street business process software, your smartphone, and the Mars rover.

But what is code in terms of its function in society? Is code simply a raw material to be transported and assembled to build products, like timber or steel? Or is it more than this?

In 2016, when the FBI wanted Apple create a backdoor to unlock the San Bernardino shooter’s iPhone, one of Apple’s arguments against doing so was that it would constitute a violation of the first amendment: that code is speech, and the FBI cannot force Apple to write new code on those grounds.

Apple told the court:

under well-settled law, computer code is treated as speech within the meaning of the First Amendment.

However, writing in MIT’s Technology Review, Professor Neil Richards, disputes this statement and challenges the idea behind it. On a legal basis he makes the point that the Supreme Court has not come to this conclusion, only some lower courts have passed judgements suggesting code may equal speech.

Richards argues that the first amendment is related to expression and protection of that expression from Government intervention, suggesting that “speechiness” should be assessed for different kinds of expression in order to determine whether they fall under the parameters of the amendment:

Code = Speech is a fallacy because it would needlessly treat writing the code for a malicious virus as equivalent to writing an editorial in the New York Times.

As he mentions, the Supreme Court has already held up the equivalency of money as speech, notably leading to Citizens United, so the potential for that precedent to continue is real.

Further discussions of the relationship between code and speech can be seen in the early work of Lawrence Lessig, whose text What Things Regulate Speech? provides an interesting look at.

Lessig’s famed contribution is less that code = speech, as code = law. In his article, Code is Law for Harvard Magazine, he explains how the nature of code creates a form of social regulation. He argues that, much like the Founding Fathers created the constitution to reign in the emergence of a large federal state, and John Stuart Mill wrote On Liberty to balance against the oppressive social mores of the time, so too do we need to find ways to tame and calm the emergence of code as a social regulator.

This regulation is changing. The code of cyberspace is changing. And as this code changes, the character of cyberspace will change as well. Cyberspace will change from a place that protects anonymity, free speech, and individual control, to a place that makes anonymity harder, speech less free, and individual control the province of individual experts only.

The question of what code really is, in a metaphysical sense, is not just an amusing thought but is actually a foundational question in understanding how a future world will come to be shaped, and to what extent we can impact upon it.

Is the singularity real? should we be worried about it?

The singularity is a hot topic and one which seems to divide people often.

At the World Ethical Data Forum, Ralph Merkle asked for a show of hands to see what proportion of the room thought the singularity was something we should perhaps be concerned about. I’d estimate about 75% were raised.

The singularity is roughly the idea that there will be a computer so intelligent that it won’t need humans and we’ll move into an age where computers are to some extent in control.

There are many competing ways this idea has been expressed; from a singular supercomputer to a more benign series of computerized processes which shape and define the world we live in, largely outside human involvement.

One of the first people to suggest this reality was I J Good, who wrote in 1965:

Let an ultraintelligent machine be defined as a machine that can far surpass all the intellectual activities of any man however clever. Since the design of machines is one of these intellectual activities, an ultraintelligent machine could design even better machines; there would then unquestionably be an ‘intelligence explosion,’ and the intelligence of man would be left far behind. Thus the first ultraintelligent machine is the last invention that man need ever make.

It all sounds a lot like science fiction, but when scientists like Stephen Hawking and tech-moguls like Elon Musk are all worried about it, we should probably take it seriously.

Emeritus professor of computer science, Vernor Vinge, in his essay The Coming Technological Singularity lays out his belief that this moment of advancement will signal the end of the human era and the birth of a new age of civilization.

However, there is possibly reason to be more cheerful. One of Vinge’s proposed outcomes is:

Computer/human interfaces may become so intimate that users may reasonably be considered superhumanly intelligent.

Which I think we can all agree would be quite nice.

As the movement toward the singularity goes, further advances like quantum computing and organic computing could play their role in this technological revolution.

One issue with the idea of the coming singularity might be the existence of limits to how this advancement could be achieved. Jeff Hawkins argued:

Belief in this idea is based on a naive understanding of what intelligence is. As an analogy, imagine we had a computer that could design new computers (chips, systems, and software) faster than itself. Would such a computer lead to infinitely fast computers or even computers that were faster than anything humans could ever build? No. It might accelerate the rate of improvements for a while, but in the end there are limits to how big and fast computers can be. We would end up in the same place; we’d just get there a bit faster. There would be no singularity.

Adding, that if this upper limit was high enough then there is a chance it would be indistinguishable for humans from the singularity anyway.

Interesting times ahead, either way!

How do we combat digital monopolies?

On a more grounded note, there are issues arising right now relating to the global reach and power of single entities.

Google may not be an AI controlling the world, but it does leverage huge power across the world. It hoovers up data and acts as a gatekeeper of information for many of the web’s users.

There’s a centralization of control occurring with some of the largest software companies. Organizations like Facebook, Alphabet, and Amazon in particular are expanding their power and operations in ways which create huge monolithic monopolies.

The reach of these platforms has become enough to impact on, for example, elections. The Trump campaign strategy and the Brexit campaign strategy really went hard on promoting themselves via Facebook retargeting – something I covered in an article of mine on the science of persuasion, with a step by step guide to how psychometrics were leveraged by Cambridge Analytica.

This new kind of dominant software company has come to be described using a concept called platform capitalism. The LA Review of Books has an excellent article titled Delete Your Account: On the Theory of Platform Capitalism which does an effective job of summarizing and analyzing much of the contemporary literature on the topic.

The term platform capitalism came from a German theorist called Sascha Lobo. But what do we mean when we talk of platforms in this sense? Nick Srnicek explains the base of this idea writing for IPPR:

Essentially, they are a newly predominant type of business model premised upon bringing different groups together. Facebook and Google connect advertisers, businesses, and everyday users; Uber connects riders and drivers; and Amazon and Siemens are building and renting the platform infrastructures that underlie the contemporary economy. Essential to all of these platform businesses – and indicative of a wider shift in capitalism – is the centrality of data.

The argument goes that this mass exchange of data holds the potential for the gross economic power these companies’ wield.

If we take an example: Amazon monitor everything which third-party retailers sell through their platform. If batteries are sold at a high rate and with a reasonable markup, then Amazon know. Amazon can then sell their own brand batteries on their site and crowd out their competitors.

Amazon do this with loads of products. They know what will bring them money before they launch a product because they hold the data; they have a competitive retail advantage over practically every other retailer in the world thanks to this data.

But just as more and more data is needed to be an effective platform, this means that privacy and other online “rights” are eaten away. The platforms feed on data to fuel their expansion. It’s capitalism like you’re used to, but it now wants to know what you’re doing every hour of the day – what you’re thinking, preferably.

This expansion of scope and invasion of privacy is necessary for growth, while the network effect which compounds the success of this data-vacuum serves to centralize the power of this data and keep it held in a relatively small number of hands.

Many digital management thinkers like Scott Galloway or Franklin Foer propose ways to disrupt the big platforms or slow them down, but as yet we don’t seem to know where we’re heading or how we should react to this new found dominance…

3 challenges discussed at the World Ethical Data Forum

The World Ethical Data Forum was held in Barcelona and covered a range of topics relating primarily to ideas of digital freedom.

I felt this theme was a recurring one which almost all talks touched on at one point or another, or formed their central thesis.

Much of the discussion was centered around the blockchain and its potential applications, with a strong emphasis on the positive social good it could be responsible for if utilized effectively.

This pivoting of conversation away from cryptocurrency to the underlying technology feels to me like a sign that the industry is maturing somewhat and starting to look for long-term applications of the tech.

The practical challenges of protecting private medical data

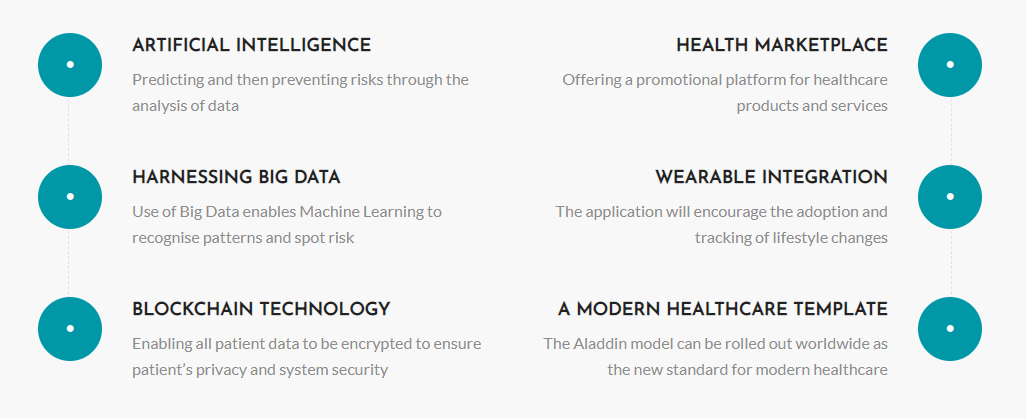

Dr. Fenglian Xu, chief scientist at Aladdin Blockchain, presented her ongoing research and development in a talk about the potential role of blockchain in healthcare, looking to solve problems relating to privacy and security.

Xu comes with a strong resume having formerly developed a range of blockchain technologies at IBM, including being the co-creator of the IBM Hyperledger.

Xu outlines the rate of growth of the healthcare market in China and the ways in which the infrastructure is being built. She identifies this market as a potential space where blockchain tech could be utilized to provide services relating to patient data.

Right now, data privacy is huge in healthcare. Current systems are not strong enough to maintain security, nor are they always flexible enough to function optimally on the ground.

In a previous article on the challenges of bureaucratic organization, I discussed the way Estonia were employing the blockchain to give patients more control over their own data. It seems this trend may be continuing.

Xu describes how 3.14 million medical records were exposed in Q2 of 2018 alone. The problem is clearly large, but what are its constituent parts?

She outlines 4 key contributing factors:

- There are a lack of adequate industry standards or controls.

- There is limited transparency in how data is held, where it is held, and who has access to it.

- Most data is stored in massive data silos which creates inherent security risks.

- Data escape is a common problem, often motivated by the prospects of selling medical data onto the black market.

The proposal would be to construct better forms of data storage with greater levels of control over access and increased transparency.

In an ideal world, this data could be anonymized and opened up to an extent for medical research. With the vast amounts of data in the collection, AI technology could perform trend analyses in order to better understand factors which appear to relate to one another to help guide medical researchers in their attempts to improve public health.

This kind of analysis requires state of the art technology to operate. In January 2018, IBM announced a proof-of-concept for their blockchain-based know your customer (KYC) tool which would allow, in this case banks, to access and analyze the data they’re holding while keeping the information encrypted.

This allows for data to be shared securely while remaining actionable. These ways of leveraging the blockchain look likely to come into force in Asia in certain industries sooner rather than later:

This initiative aligns with the Monetary Authority of Singapore’s vision to drive innovation in modernizing Singapore’s Finance Infrastructure, and at the same time, enhances transparency into KYC processes performed by Banks.

The question for Xu is whether these same techniques can be applied effectively onto healthcare. If they can, the benefits are there to be reaped by both the end user and the medical research community as a whole.

How to build a digital democracy for the future

When thinking about ethics and the challenges facing us, it’s impossible not to look at politics.

Ralph Merkle, who has won countless awards but is particularly relevant here for being one of the creators of public key cryptography and the inventor of cryptographic hashing, decided that the blockchain could tackle exactly this.

Merkle outlines his theory in a whitepaper titled DAOs, Democracy and Governance where he goes into extensive detail explaining how a DAO democracy would work and the various considerations which need to be kept in mind.

It is premised on the quote, variously attributed, that democracy is the worst form of government except for all the rest.

Merkle goes on the basis that much of the voting public are not capable of consistently making well informed political or policy decisions. He highlights his primary concerns with voting as it exists in Western representative democracies:

- There is little economic incentive to vote.

- Lots of effort is required in order to vote in an informed way.

- Lots of effort is put into disinformation campaigns to mislead voters.

- Candidates don’t always do as promised.

- Not all voters are smart.

Yet, equally, disenfranchising segments of the public often results in repression or even tyranny as those with power seek to service it in their own interests.

So, we need a decision making mechanism which can be effectively utilized with the intention of providing benefit to all. That’s the starting point for Merkle.

It’s here where the concept of a DAO comes in. DAO stands for decentralized autonomous organization. The idea is that it is an organization which runs on the basis of rules encoded as a computer program. These rules are transparent and every member of the DAO is a stakeholder in the organization.

This DAO would seek to achieve self-improvement, making the new kind of government better and in turn improving the lives of the people.

Merkle comes up with an interesting way to do this. The first is to calculate the collective welfare. He proposes this could be done by asking everyone to rate their welfare, or quality of life, on a 1-100 scale each year. With enough data you can pull out average scores for the society for each decade.

This gives us a democratic element. The idea would be that bills brought forward to change the DAO would have to be seen to improve the Collective Future Welfare – they would be assessed on whether they look likely to improve the aggregated self-reported welfare score.

Merkle proposes that we use a Prediction Market mechanism to assess whether a bill would increase the Collective Future Welfare. If the market believes it will do, then the bill passes.

The prediction market idea is that you put out an offer for whether the bill would improve society’s lot and an offer that suggests the opposite. Whichever the market bets on, determines the output of the test.

Merkle doesn’t suggest that this is a perfect decision making mechanism but believes that it is as effective or more effective than existing models.

So – to break it down:

- Government operates hard coded and transparent on the blockchain

- People are polled about their welfare each year

- The market bets on bills presented to government on the basis of whether they would increase overall welfare

- If the market thinks a bill will increase Collective Future Welfare, it passes

It is not meant to be the perfect system, but it is meant to be better than the current one and less open to corruption.

I’m not sure whether I’m sold.

For me, the big worries would be:

- The lack of appreciation for the complexities of government activity and the amount of power than can come with being an apparatchik. Would the government need to be slimmed down drastically to operate in this manner? If so, is this not simply enforced libertarianism?

- The idea that there is a notion of the correct political decision; the ultimate technocracy. Perhaps governance is messy because different groups have competing interests? Would the rigid nature of a DAO adapt well to this, particularly when the decision making function is reliant on market approval?

- If people are told by powerful moneyed groups that their lives are better than before, might they believe them even if the difference is minimal? Merkle identified misinformation as a problem in democracy; is it unreasonable to suggest it could equally be a problem in this system too?

Nonetheless, Merkle’s ideas are not without merit. I very much encourage anyone to read his whitepaper and make your own assessment.

Merkle’s proposals demonstrate the new kinds of political structures we could construct if we were to leverage technology in new ways. Maybe we need to construct new structures?

Digital freedoms in a surveillance state

The work of Jean Le Carré will likely be familiar to you all. If you like it, then you’ll be fascinated by Annie Machon and her tale of escape from inside the belly of the intelligence services.

Her speech was titled The Dark Triad, a psychiatric concept to describe the collection of three personality traits:

- Machiavellianism

- Narcisism

- Psychopathy

Her story begins 28 years ago. Having completed her studies in classics at Cambridge, Machon applied to the Foreign Office. Instead of taking up her role as a civil servant, Machon was sent to interview for Mi5.

Though she was hesitant at first their insistence that they wanted to hire “a new kind of agent” put her somewhat at ease and convinced Machon to join the intelligence community.

During her time in the organization she worked three different sections:

- Political

- Irish

- International

She’d seen a broad scope of the activities of Mi5 and attempted to request internally for things to be changed. These requests were turned down.

In 1996, Machon and her partner, also a spy, resigned and leaked documents to the press. Two of the main claims levied at Mi5 were:

- That Mi5 knew the accused terrorists of the attack on the Israeli Embassy in 1996, and knew they were innocent students yet chose to repress that info.

- That Mi5 had funded Al Qaeda to attempt to assassinate Gaddafi. The assassination was unsuccessful but others died in the incident.

However, the newspapers at the time didn’t want to run the main stories. This theme rises again later on when Machon and her partner had to appear in court; the press misreported the trial while leaving out pertinent information, such as claiming the leaks had been done for money rather than public interest.

Machon’s talk touches upon a number of key points:

- While she was a security agent, the intelligence services had extensive files on politicians, activists, and more.

- She claims that Mi5 had mislead parliament, calling into question their role in upholding democracy.

- Via GCHQ, the NSA, and the Five Eyes program, everything we do is monitored and logged – now public knowledge.

- Machon claims that post-2008 hardware is compromised and that your end-to-end encrypted messages are essentially useless.

- Moreover, she reinforces the point that social networks have built in backdoors anyway.

The long and short of it is that we are living in an increasingly surveilled world where privacy no longer really exists.

In the context of digital ethics, we need to be able to unpack this situation and assess its merits and failings – of which I would argue there are many.

Moreover, any suggestion about making society better or restoring privacy in a digital age cannot come to a reasonable or actionable conclusion while it ignores the current state of play.

What to look out for in the future of digital ethics

Finally, let’s end with a couple of more uplifting topics – veering into the science fiction – to see what kind of questions still require asking.

Transhumanism: The future of being a person

Technology has already had an impact on how we live our lives in ourselves.

If you can’t see in the distance you can wear this kind of streamlined minimalist face-mask which enhances the appearance of everything around you – I think we call it spec-ta-cles.

Well, that might not be the peak of human enhancement we thought it was. Though the cyborgization of the human body kind of began when we first wore other animals’ furs for warmth, the future of human enhancement looks to be a good one.

From anything to giant robot suits to assist in getting tasks done, to movable and touchable prosthetics which can replace lost limbs. We may grow new hearts in labs or go full Black Mirror and have implants record our memories.

More than this, some scientists – backed by moguls like Musk – are working on creating a streamlined connection between the human brain and computers. Musk’s Neuralink may not work on the first run out, but the chance of immortality in the cloud is genuinely almost here.

Plato once described humans as featherless bipeds (and was rightly mocked by Diogenes). As we continue our technological march forward, how will our future selves identify with humanity? What will it mean in the future to be human?

Or will the Greek philosophers be right, and we’ll still just be a plucked chicken running around aimlessly?

How will robots think?

Nevermind what it means to be human. What will it mean to be a robot?

It’s a pretty pertinent question if you’re of the belief that they’ll be running the show in the not too distant future.

Our monkey brains are limited and confined to their nature, to some extent. That’s why we’re having largely the same conversations now as our pals Plato, Aristotle, and co were having 2500 years ago. There isn’t really the timespan for us to make evolutionary changes as a species, we pretty much have to operate with the existing organic infrastructure we have.

Robots on the other hand have a whole range of options.

Paul Thagard, philosopher of mind and cognitive scientist, doesn’t expect robots to be particularly similar to humans, but doesn’t rule it out.

In fact, he thinks it may be expedient to make robots in some way more human; to give them emotions:

According to obsolete ideas, rationality and emotion are fundamentally opposed because rationality is a cold, calculating practice using deductive logic, probabilities, and utilities. But there is abundant evidence from psychology, neuroscience, and behavioral economics that cognition and emotion are intertwined in the human mind and brain. Although there are cases where emotions make people irrational, for example when a person loves an abusive spouse, there are many other cases where good decisions depend on our emotional reactions to situations. Emotions help people to decide what is important and to integrate complex information into crucial decisions. So it might be useful to try to make a robot that has emotions too.

Adding on to this, it is likely helpful if a robot has emotions because it might help them be more empathetic to us – either professionally for care work, or in case of an extreme situation where we might want a robot to value our life, happiness, or general welfare.

So, maybe being a robot might be more like being a human than we expect? Because we build them that way.

It’s one to consider. Come the singularity, though, they could just rewire themselves in their own image and all our efforts may be in vein…

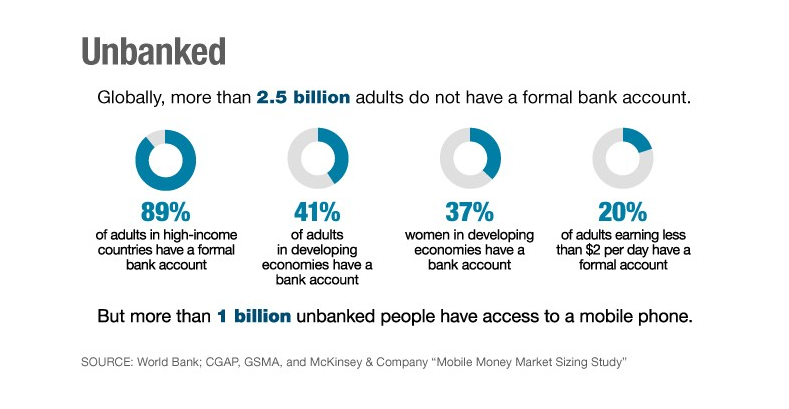

Banking the unbanked

A much more grounded and current question. How can we use technology today to add stability to developing economies and security to the lives of those living there?

In a way, blockchain advocates have seen this as a point of entry as the world’s financial markets go.

Much of the world is without a bank and they seek something more secure than storing a wildly fluctuating currency under a mattress.

This is where technologies based on the blockchain are turning up to help provide a little assistance in formalizing the financial flows of an individual or a community.

CoinTelegraph outline the challenge:

Blockchain technology has the potential to help the unbanked and underbanked by allowing them to create their own financial alternatives in an efficient, transparent and scalable manner.

And they lay out 3 companies they believe are attempting to make an impact into this space:

In discussions of ethics, it can sometimes be easier to take grand thought experiments and hypotheticals, but we do need to realize that real people have real needs right now. While the human consciousness fails to be uploaded to the cloud for the umpteenth time, new people around the world are gaining financial stability.

Should we live on Mars?

It was always going to end with another of Musk’s projects, wasn’t it?

We’ve written before about his production systems, but the Gigafactory is just less interesting inherently than the idea of humans becoming a multi-planetary species.

Musk basically believes we’re going to cock Earth up. Eventually. One way or the other.

The only way to make sure we don’t make ourselves extinct is to have human civilizations on other planets too. That way, if we nuke ourselves on one planet, we just carry on life on another one.

SpaceX is the baby steps in Musk’s plan to do this – to take us to outer-space and, ideally for him, off to Mars.

And, you know what? As long as there are no child submarines, I’m on board.

According to USA Today, I’m not the only one on board:

Humans will “absolutely” be on Mars in the future, NASA chief scientist Jim Green told USA TODAY. And the first person to go is likely living today, he said.

There seems to be a real sense of optimism surrounding the idea of colonizing Mars, but it does also raise some questions:

- Shouldn’t we also be really working hard to look after earth?

- Are we going to treat every planet as badly as we’ve treated this one?

- Who’s going to go to Mars?

The idea of colonization is less exciting if I’m here eating rats in a nuclear holocaust while Elon is on his space beach sipping Moonjitos (big shout out to Espresso Martianis).

Can digital ethics shape the world of tomorrow?

It’s a difficult question.

It’s all well and good us discussing the ethics of current and future technological impact, but if the power to make substantive changes to this reality lies with others who profit off the tech, then it might just be happening anyway.

Legislation like GDPR has shown us that ethical discussions of technology can impact on lawmakers and assist in driving change – but we’re yet to see how effective GDPR becomes in the coming years.

Or, maybe mass automation will come sooner than we think and the first to go will be philosophers? It’s unlikely, but as we outlined above: we don’t know how robots will think. So it’s anyone’s guess.

At the very least, these kinds of issues should enter into the public discourse sooner rather than later in a hope that our preparedness as a species improves.

What hot topics in digital ethics interest you most? Let us know your thoughts in the comments below!

Workflows

Workflows Forms

Forms Data Sets

Data Sets Pages

Pages Process AI

Process AI Automations

Automations Analytics

Analytics Apps

Apps Integrations

Integrations

Property management

Property management

Human resources

Human resources

Customer management

Customer management

Information technology

Information technology

Adam Henshall

I manage the content for Process Street and dabble in other projects inc language exchange app Idyoma on the side. Living in Sevilla in the south of Spain, my current hobby is learning Spanish! @adam_h_h on Twitter. Subscribe to my email newsletter here on Substack: Trust The Process. Or come join the conversation on Reddit at r/ProcessManagement.