VALUES

The movement is built on three different pillars: swarm work, traditional NGO structures, and a hierarchical topdown structure that distributes resources to support the swarm. These are roughly equally important, but fill completely different needs; the hierarchic work distribute resources and associated mandates from the board into the organization, making decisions for effective opinion building and other operative work; and the spontaneous swarm work is the backbone of our activism.

We work under the following principles:

We make decisions. We aren’t afraid to try out new things, new ways to shape opinion and drive the public debate. We make decisions without asking anybody’s permission, and we stand for them. Sometimes, things go wrong. It’s always okay to make a mistake in the GLM, as long as one is capable of learning from that mistake. Here’s where the GLM's "three co creators rule” comes into play: if three self-identified co-creators are in agreement that some kind of activism is beneficial to the party, they have authority to act in the movements name. They can even be reimbursed for expenses related to such activism, as long as it is reasonable (wood sticks, glue, and paint are reasonable; computer equipment and jumbotrons are not).

We are courageous. If something goes horribly wrong, we deal with it then, and only then. We are never nervous in advance. Everything can go wrong, and everything can go right. We are allowed to do the wrong thing, because otherwise, we can never do the right thing either.

We advance one another. We depend on our cohesion. It is just as much an achievement to show solitary brilliance in results as it is to advance other co-creators.

We trust one another. We know that each and every one of us wants the best for the Earth.

We take initiatives and respect those of others. The person who takes an initiative gets it most of the time. We avoid criticizing the initiatives of others, for they who take initiatives do something for the movement. If we think the initiative is pulling the movement in the wrong direction, we compensate by taking an initiative of our own more in line with our own ideals. If we see something we dislike, we respond by making and spreading something we like, instead of pointing out what we dislike. We need diversity in our activism and strive for it.

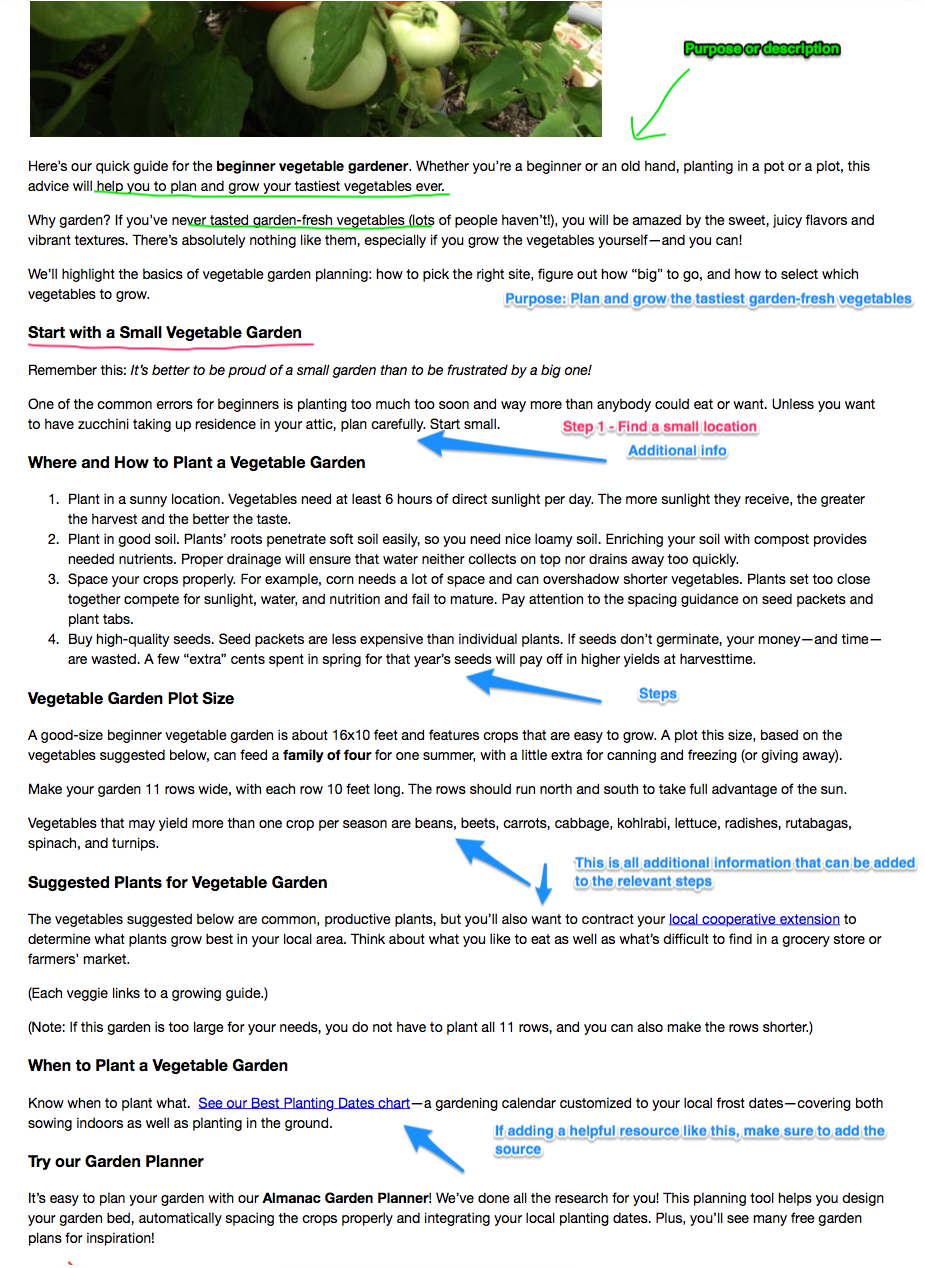

We respect knowledge. In discussing a subject, any subject, hard measured data is preferable. Second preference goes to a person with experience in the subject. Knowing and having experience take precedence before thinking and feeling, and hard data takes precedence before knowing.

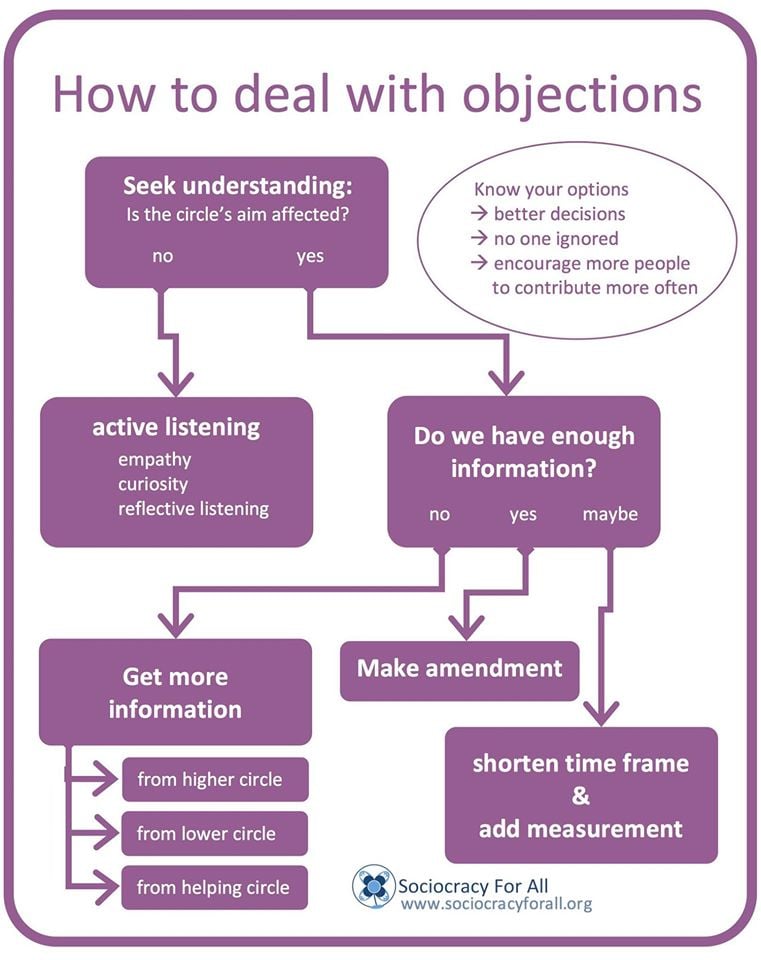

We respect the time of others and the focus of the organization. If we dislike some activity or some decision, we discuss, we argue, we disagree, and/or we start an initiative of our own that we prefer. On the other hand, starting or supporting an emotional conflict with a negative focus, and seeking quantity for such a line of conflict, harms the organization as a whole and drains focus, energy, and enthusiasm from the external, opinion-shaping activities. Instead, we respect the time and focus of our co-activists, and the focus of the movement. When we see the embryo of an internal conflict, we dampen it by encouraging positive communication. When we see something we dislike, we produce and distribute something we like. We work actively to spread love and respect, and to dampen aggression and distrust. We communicate positively. If we see a decision we dislike, we make our point about why we dislike it without provoking feelings, or, better yet, we explain why an alternative would be better. We campaign outward and cohesively, not inward and divisively. Again, we communicate positively.

We act with dignity. We’re always showing respect in our shaping of public opinion: respect toward each other, toward newcomers, and toward our adversaries. We act with courtesy, calm, and factuality, both on and off the record. In particular, we’re never disrespectful against our co-activists (one of the few things that GLM will have zero tolerance with).

We represent ourselves. GLM depends on a diversity of voices. None of us represents the GLM on blogs and similar: we’re a multitude of individuals that are self identified liberation Co-activist. The diversity gives us our base for activism, and multiple role models build a broader recruitment and inspiration base for activism. Internally, we’re also just ourselves, and never claim to speak for a larger group: if our ideas get traction, that’s enough; if they don’t get traction, the number of people agreeing with those ideas is irrelevant.

LEADERSHIP

Leading in the movement is a hard but rewarding challenge. It’s considerably harder than being a middle manager in a random corporation. On the other hand, it’s somewhat easier than sending letters by carrier mackerel across the Sahara. Above all, it is stimulating, exciting, and simply quite fun. The challenges lie in the constant demands for transparency and influence from your area of responsibility, combined with the demands for results and accountability from those you report to. Basically, this means that leadership in the GLM is a social skill, rather than a management or technical skill. It is about making people feel secure in their roles.

Above all, we need to defend two things in all our actions:

— The movements focus

— The organization’s energy. It is incredibly easy to get drained of energy if you start feeling negative vibes. There is a need for a constantly reinforced we-can-do-this sentiment.

In order to sustain these two values, we who have taken on co-activists responsibility use the following means:

Monkey see, monkey do. We are role models. We act just the way we want other people in the organization to act. One part of this is to always try to be positive. In all organizations, the organization as a whole will copy its leaders. When we yell at somebody, we spread the culture of yelling at one another. When we advance and praise people for what they do, we spread the culture that people should advance and praise one another. Therefore, we do the latter.

This can be hard. An example is in forums where we find ourselves in a discussion with somebody who seems to be wrong. It’s easy to take on an irritated tone of voice and use condescending language (for a funny illustration of this phenomenon, look up the URL http://xkcd.com/386/). We must avoid this by being aware of the risk and counteracting it. This goes especially for net-only communication, where important parts of communication such as body language, emphasis, and tone of voice just disappear, parts that would otherwise have reduced the experienced aggression in many comment fields. Attitudes are highly contagious, so, therefore, we make sure to have a positive and understanding attitude. We spread love, trust, energy, and enthusiasm.

We make decisions. We have had decision-making authority delegated to us in some area of the organization, and we use it. We are not afraid of saying, “I make this decision,” because it is our express and explicit task to make decisions independently and then stand for them. The opposite would be if we let everybody have a say in everything. We don’t operate like that. We make decisions by ourselves; we have standalone decision makers. You are one of them. Also, we avoid voting to the extreme and only use it as a very last resort: voting creates losers

However, our being decision makers is no excuse for treating the mandate with disrespect. We treat everybody affected by our decisions with just as much respect as we need ourselves to keep enjoying respect as leaders and decision makers. Decisions shall be used to strengthen the movements energy and focus, and a decision that makes harmfully large portions of the organization upset about the decision in itself should be rescinded. This calls for an independent striking of a balance between making independent decisions and our dependence on the trust of the affected to keep making decisions, and the grayscale is quite large.

We lead by inspiring and suggesting, never by commanding. In a swarm, nobody can or should be told what to do. We do not have any kind of mandate to point at people and tell them to do things. Rather, we must inspire them to greatness. We cause things to happen by saying aloud that “I’m going to do X, because I think it will accomplish Y. If enough of us do this, we could probably cause Z to happen. Therefore, it would be nice to have some company when I do X,” or something along those lines in our own words.

We advance role models. We reward our colleagues as often as we can, both in public and private, when they display a behavior we want to reinforce. In particular, this goes for activists who advance their colleagues. We praise and reward individual brilliance as much as helping others to shine. This is important.

We reward with attention. Every behavior that gets attention in an organization is reinforced. Therefore, we focus and give attention to good behavior, and, as far as possible, we completely ignore bad behavior. We praise the good and ignore the bad (with one exception below).

We assume good faith. We assume that everybody wants the movement to succeed, even when they do things we don’t understand. We assume they act out of a desire to help GLM, even if we perceive the result as directly opposite. In such situations, we show patience and encourage activism while helping newcomers make themselves comfortable in our organizational culture. In such a manner, we also display good faith ourselves as leaders and act as role models.

We react immediately against disrespect. Even if we have great tolerance for mistakes and bad judgment, we do not show tolerance when somebody shows disrespect toward his or her colleagues, toward other activists. Condescending argumentation or other forms of behavior used to suppress a co-activist is never accepted. When we see such behavior, we jump on it and mark it as unacceptable. In our leadership roles, we have an important role in making sure that people feel secure in their roles, with no bullying accepted. If the bully continues despite having the behavior pointed out, he or she will be shut out from the area where he or she disrespects his or her peers, and if some friend reinvites him or her back just for spite, we will probably shut off the friend, too. We have absolute-zero tolerance for disrespect or intentionally bad behavior against co-activists.

We speak from our own position. When we perceive somebody as being in the wrong, we never say “you’re stupid” or similar, but start from our own thoughts, feelings, and reactions. We communicate using the model “When you perform action X, I feel Y, since I perceive you think Z,” possibly with the addition “I had expected A or B.” An example: “When you give the entire budget to activism, I feel frustrated, as I feel you ignore our needs for IT operations. I had expected you to ask how much it costs to run our servers.” This creates a constructive dialogue instead of a confrontational one.

We stand for our opinions. We never say “Many people feel…” or try to hide behind some kind of quantity of people. Our opinions are always and only our own, and we stand for them. The one exception is when we represent an organization in a protocolled decision.

Administration is a support and never a purpose. We try to keep administrative weight and actions to a minimum, and instead prioritize activism. It is incredibly easy to get stuck in a continuously self-reinforcing bureaucratic structure, and every formal action or process needs to be regularly questioned to evaluate how it helps activism and shaping the public opinion

We build social connections. We meet, and we make others meet. Social connections — that people meet, eat, and have beer or coffee with each other — are what make the Pirate Party into an organization.

We develop our colleagues. We help everybody develop and improve, both as activists and leaders. Nobody is born with leadership; it is an acquired skill. We help each other develop our skills, even in our roles as officers and leaders.

Finally, all leaders and decision makers in the GLM should see the fifty-five-minute video “How to protect your open source project from poisonous people.” On the surface, it is about a technical project, but the focus is on courses of action when events pop up that disturb the focus or energy in a volunteer community. It is very applicable to the movement, too.

This is a document that is being updated as we go. It cannot be used to beat somebody over the head because a certain part can be read a certain way: the important thing is the spirit and not the letter