As an analyst, you spend your day designing your organization’s processes, measuring their performance and ironing out the fine details. You focus on the “how”. You’re very good at it, but maybe you’re more interested in the “what”? If you want to move past the nitty-gritty of processes and devise end-to-end models and strategies instead, then you’re looking make the leap to business architect.

The necessity of architects is a byproduct of digital transformation.

“There’s a growing need for talented pros who can reduce complexity, establish solid technology processes and ensure tech’s used consistently across business units and functional areas.” — Sharon Florentine, CIO

What is a business architect?

As a business architect, you will design the structure of the business as a whole by looking broadly at systems design and requirements. Your aim is to improve the business’ operations in line with goals and strategy. Architects do this by theorizing and testing the components of a system (the technology, the flow of work, the deliverables) and overseeing the implementation of the systems by someone in a business analyst role.

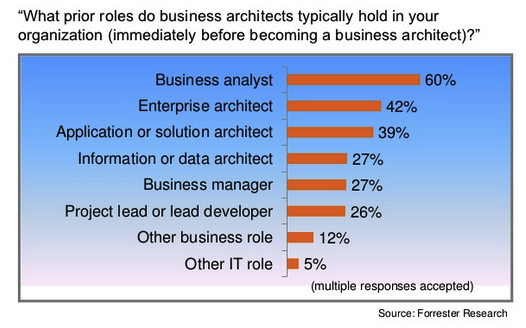

Architects earn around 70% more than analysts, with an average salary of almost $120,000. In fact, 60% of today’s architects were once analysts.

It is a natural career progression because the jobs are two sides of the same coin; one side comes up with the strategy, the other works out the fine details. Once you have an understanding of how systems work at a low level, you are more qualified to implement them from the top down while understanding how it works in practice.

As outlined in every business architect’s tome of wisdom, the BIZBOK guide, the core principles of business architecture are:

- Business architecture is about the business.

- Business architecture’s scope is the scope of the business.

- Business architecture is not prescriptive.

- Business architecture is iterative.

- Business architecture is reusable.

- Business architecture is not about the deliverables.

In the words of Cecille Hoffman, a business architect which was previously an analyst for ten years, the day-to-day of a business architect is mostly:

- Formulating frameworks and building models

- Writing concept documents

- Critiquing project proposals

- Preparing for and conducting knowledge elicitation meetings

- Asking a lot of questions

- Collaborating, facilitating, more collaborating

- Identifying “services” in product offering visions

- Tending an organic ten-year roadmap

While analysts handle something closer to technical project management in their assigned teams, IDG found that architects have “a strong relationship with the business side of the house”, but aligned more with senior IT management than analysts.

The difference between analyst and architect

According to Sergey Thorn — Member of the Architecture Forum since 2004, and Global Head of GBP IT Architecture at HSBC — business architects can be considered a senior version of analysts, with the architect designing the ‘broad strokes’ of a strategy which the analyst will implement in fine detail.

“Business Analysts are on the way to becoming Business Architects. Sometimes called IT Business Analysts, they are not strictly business or IT specialists. They write business cases (with very few technical terms), identify business requirements and often are part of a Development Team.” — Sergey Thorn, HSBC

The only universally recognized difference is that analysts work more closely with the team they’re a part of, implementing the components of systems with direction from architects rather than building end-to-end systems on their own from scratch.

“There is one real difference I see here: a business architect works in the realm of strategy, and business systems analysts are engaged with tactics. I just can’t see that as a sufficiently profound difference to call them distinct fields of study.” — Kevin Brennan, IIBA

Unlike in your role as an analyst, you’re not devising specific solutions. It’s more like coming up with reusable blueprints for buildings than it is working out which exact bricks to use. Moving to an architect position is a transition from maker to manager, which means you will need to acquire a new set of skills to match.

Your skills as an analyst will give you vital perspective on what is an isn’t possible when you’re creating architectural solutions, but there is a fair amount of theory split across multiple frameworks that you will be expected to know when you interview for the role.

In this post, we’ll look at the ways you can skill up from an analyst to an architect.

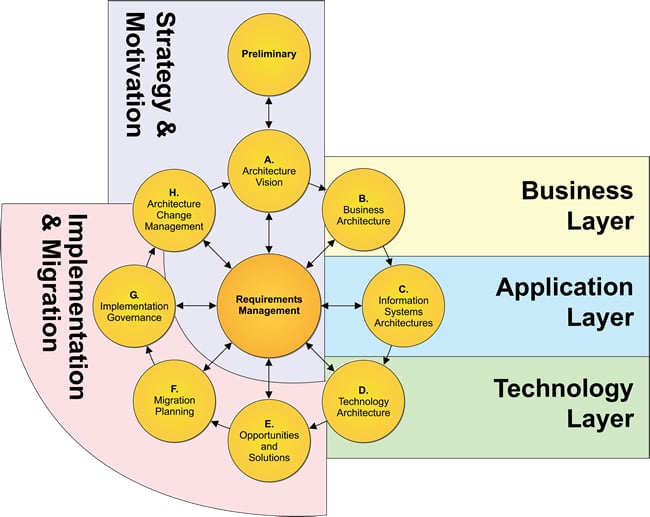

Get TOGAF certified

Bill Reynolds, IT research director at Foote Partners says that companies consider TOGAF to be “the gold standard architecture framework”.

It’s not always a concrete requirement for a job, but it is always preferred. As of 2017, only around 10,000 people were TOGAF certified, and these people most often held senior positions in the IT division of firms such as IBM, Oracle, Cisco and Deloitte. With a TOGAF certification, you become one of the elite few eligible for the best architect positions at leading companies.

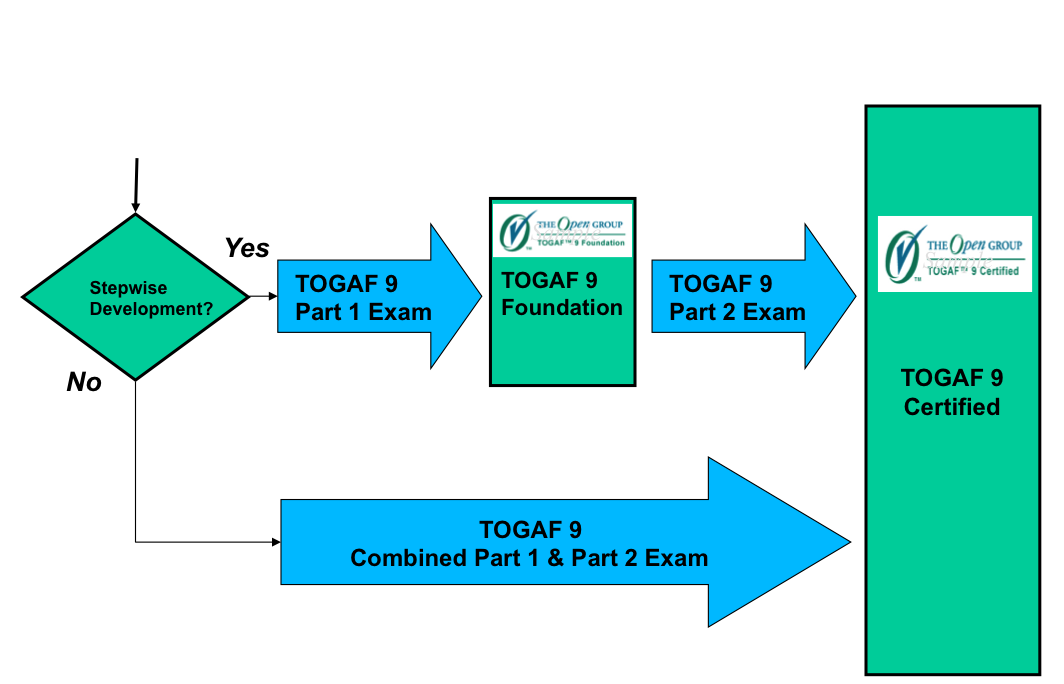

You can self-educate in preparation for the TOGAF examination, which will cost you just the price of the exams ($495 in total). The examination is conducted in two parts, allowing you to learn the foundations and the advanced topics incrementally, or simultaneously to get it done faster.

According to Dice, TOGAF is “regularly at the top of the most in-demand skills in the quarterly pay-review reports” of top IT firms, and those qualified recieve above-average pay. “There’s simply not enough architecture talent, and so pay premiums are an interim solution to get and keep people with the skills”, Reynolds says, as reported by Dice.

To get certified, you’ll need to study the materials and register for the examinations. You can take the first exam with no prior qualifications. You can also attend training sessions to brush up on your knowledge.

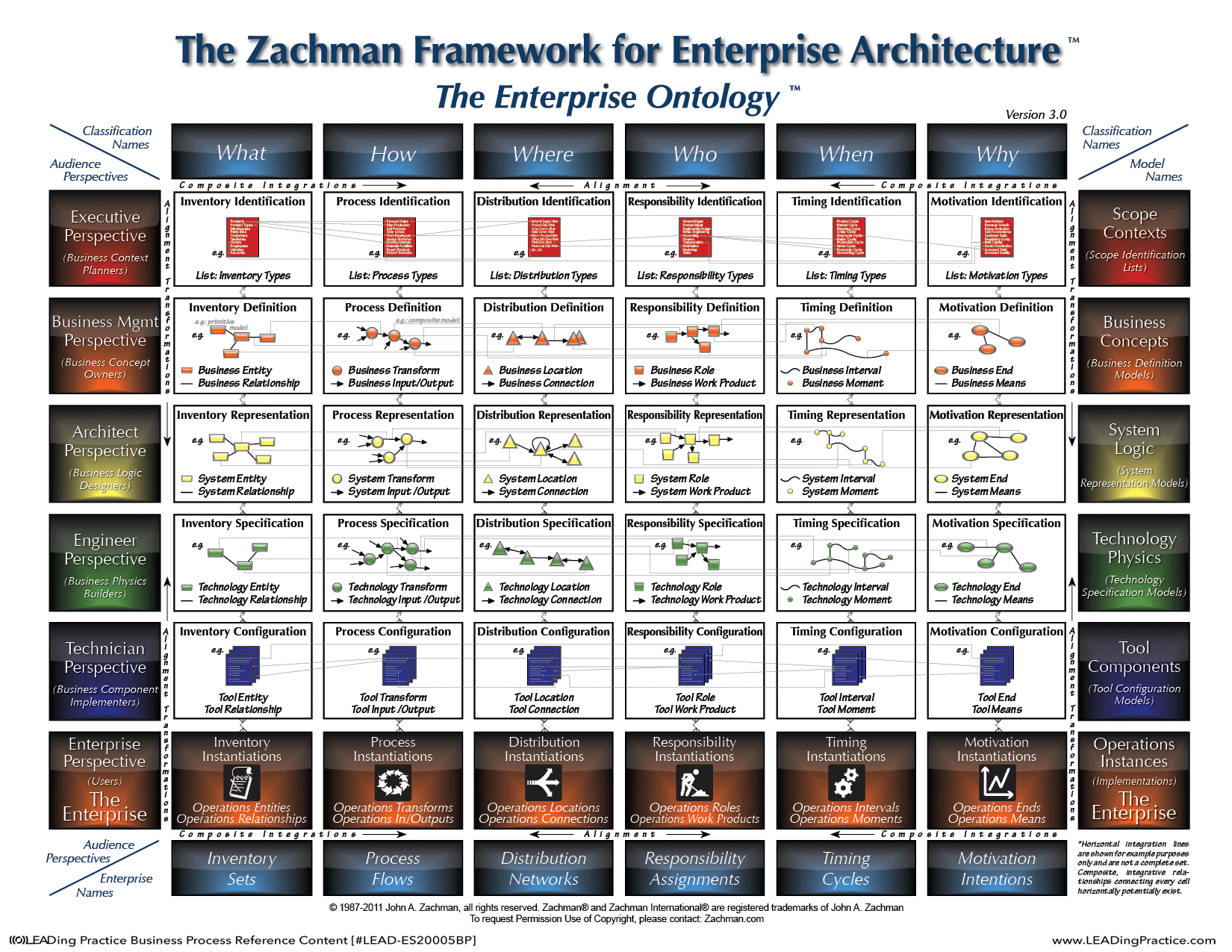

Study the Zachman framework

The image above is a visual representation of the Zachman framework, which was the first attempt to organize enterprise architecture. It was developed by John Zachman, a senior member of the IT systems staff at IBM in the 1980s. It is not a concrete methodology or set of processes, but rather a relational map showing how different elements of the business architecture intersect, and what they depend on.

The framework consists of 6 columns:

- Inventory Sets — What

- Process Flows — How

- Distribution Networks — Where

- Responsibility Assignments — Who

- Timing Cycles — When

- Motivation Intentions — Why

Each cell on the grid is a requirement. For example, one part of the architecture is the “what” of the business context — in practical terms this is the inventory of the business. When viewed from a technical perspective, inventory isn’t simply a list; to a technician, the problem of managing inventory is solved by software systems. An architect, on the other hand, would require a map of the inventory management process in order to analyze the flow.

These examples help illustrate why the Zachman framework is useful. Using it, it becomes clear which parts of the business architecture are owned by which departments and function, and what the scope of each function is.

To learn the Zachman framework, start with the original paper, check the site for the most recent version, and consider getting certified. Also, RealIRM offers Zachman framework training in two-day events.

Learn from the BIZBOK guide

Published by the Business Architecture Guild, the Business Architecture Body of Knowledge Guide (BIZBOK) is an overview of the fundamentals of business architecture, including capabilities, value streams, information, organization, stakeholders and more. The guide is essentially a crowdsourced document which comprises the experience and knowledge of “hundreds of organizations, in multiple industries, across six continents”.

To get started, you can read the introduction and table of contents for free. The Business Architecture Guild also offers a course, if you want to add another qualification to your list to increase your chances of getting your dream job.

Read Business Architecture: A Practical Guide

For years, the pioneers of business architecture were working to their own standards. Some, like Zachman, developed their own frameworks and definitions. But as IT came to play a bigger and bigger role in the modern organization, architects found that their methods needed to be organized into a schema. Groups such as the Business Architecture Guild and Business Rules Community formed to develop open standards collaboratively. Business Architecture: A Practical Guide was a long-awaited codification of the field’s methodologies and knowledge.

The authors are Jonathan Whelan and Graham Meaden, both experienced Business Architects with decades of experience. A broad spectrum of businesses has benefited from his observations and a number of his insights have led to significant programmes of work. Whelan is a Chartered Engineer and a Fellow of the British Computer Society, and Meaden headed up enterprise architecture for HSBC Group.

Find a copy of the book here.

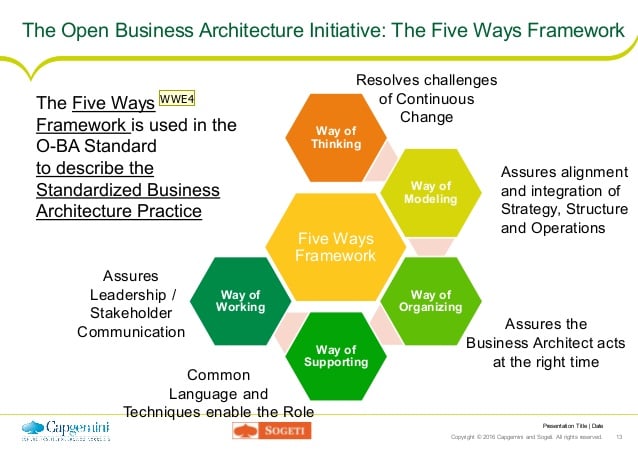

Study the Open Business Architecture Standard

According to Peter Harrad, Enterprise Architect for Ashlar Digital, the TOGAF material is lacking when it comes to offering practical methods for transformation. However, The Open Business Architecture Standard fills the gap. The standards are designed to help architects align, govern, and integrate the organization as they move through business transformation.

They also contain an explanation of the Open Business Architecture Initiative’s popular Five Ways framework, which is a way to facilitate transformation with minimal snags or confusion.

Parts one and two are available from The Open Group’s site. Download part one and part two for free in PDF.

Understanding the path to business architect

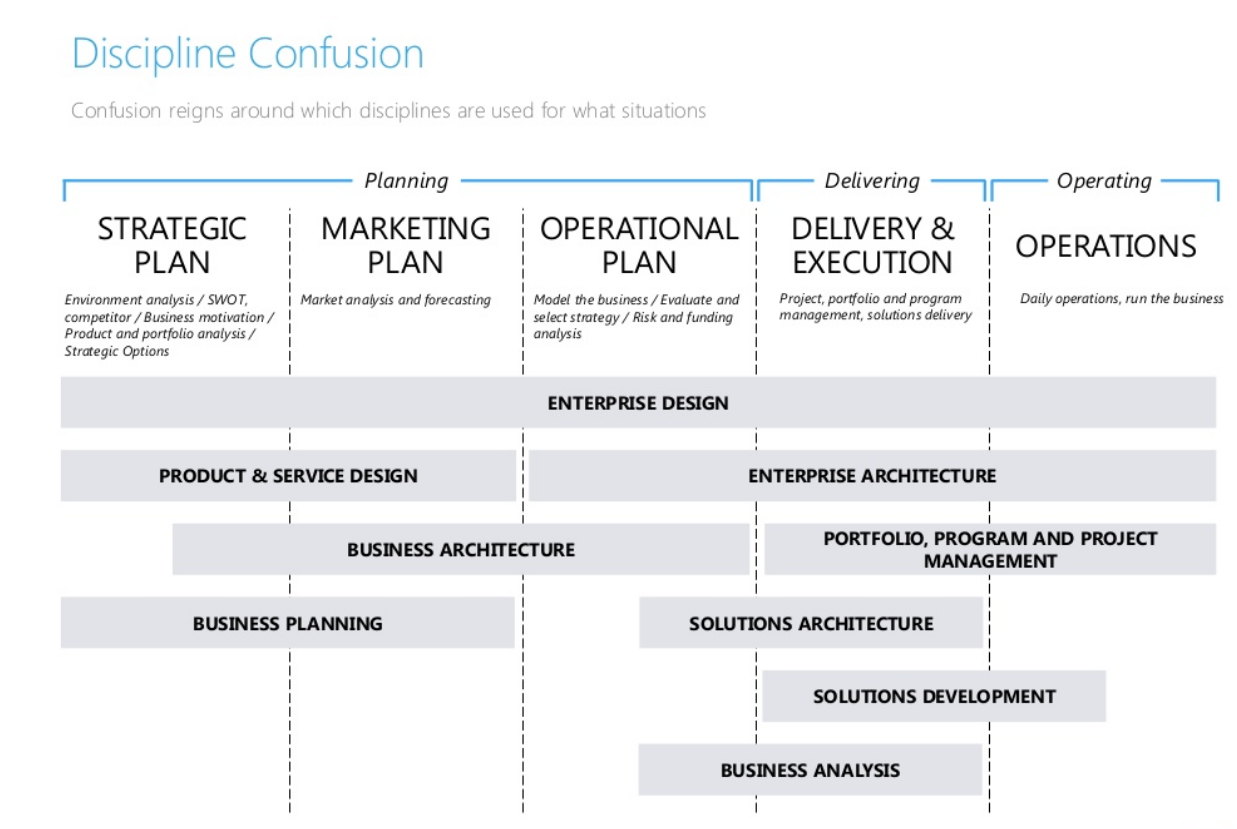

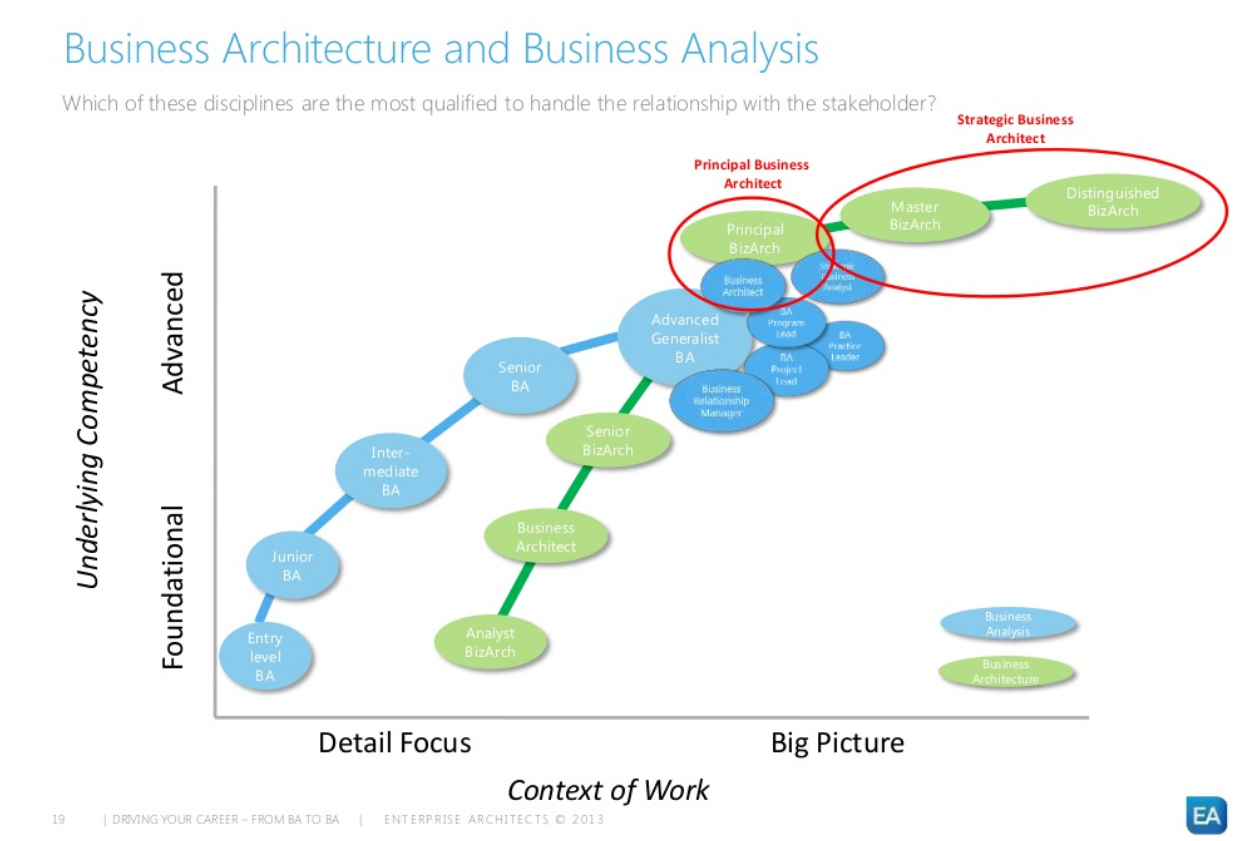

As you can see from the graphic above, as your seniority increases so does your focus on the big picture over the concrete details. The road to becoming a business architect usually starts from an analyst position, where the most junior analysts work on solving the lowest level problems. The more advanced the skillset, the more options there are for specialization.

Any tips for advancing your career as a business analyst? Let us know in the comments!

Benjamin Brandall

Benjamin Brandall is a content marketer at Process Street.