We make 226.7 decisions a day on food choices alone.

In an ad for their To-Do app, Microsoft claimed we make a whopping 35,000 decisions per day.

No one knows where they got this number from, though it is widely quoted by Inc., Huffington Post, and even academics. The fact is, a majority of decisions are made subconsciously, so even if we counted every decision we were aware of, we still wouldn’t have an accurate number. Suffice it to say, our brains field more information than is fathomable.

So how do you know you’re making the right decisions?

There aren’t likely to be severe consequences if you choose roast beef over grilled cheese for lunch (though there may be if you opt for that service station sushi), but the decisions made by your company are a whole different kettle of fish.

That’s why you need a decision support system (DSS). This Process Street post will break down the top 3 proven DSS for business operations, making your decision process just a bit easier.

Up next:

Let’s dive in!

DSS #1: DACI

I’ve written about DACI before. It’s a DSS that we’re pretty fond of here at Process Street.

As frameworks go, DACI is an incredibly useful tool for combating the obstacles in group decision-making – which, as we all know, can be a huge time sink if not managed correctly.

DACI stands for:

- Driver: Who drives a decision to a conclusion?

- Approver: Who approves a particular decision?

- Contributor: Who contributes to a decision?

- Informed: Who is informed about the final decision?

DACI focuses on who will drive the decision-making process – which is great for project managers.

It’s important to keep in mind that the Driver usually isn’t the decision-maker in this system; that responsibility belongs to the Approver(s). The Driver’s responsibility is to ensure that the decision is made.

With one person helming the process, there’s more continuity and clarity about who is responsible for delivering what and when.

The DACI process is designed to take place during a single meeting (the “kickoff meeting”). The kickoff meeting is where the bulk of the group effort comes in. The agenda for this meeting should generally follow this setup:

- Document the meeting details and attendees

- Outline the (predetermined) agenda

- Review action items and deadlines

- Assign the Driver and Approver roles

- Determine who the Contributors will be

- Specify who needs to be Informed

- Delegate tasks and agree on deadlines

(Access our DACI Meeting Checklist for the full step-by-step process.)

One of the (many) reasons Process Street uses DACI is its flexibility. We’re remote company so it’s always a challenge to get everyone together. The DACI kickoff meeting can take place in person or virtually, and synchronously or asynchronously.

For example, you can use a collaboration app like Trello or Airtable that each person can add their contributions to. For conducting asynchronous meetings, we really like Slack.

(So much so that we developed the Slack App, which brings your Process Street workflows and tasks directly into your Slack workspace.)

DACI in action

A typical scenario for an asynchronous kickoff meeting would be our monthly sprint planning process. This is when we establish what content needs to be created – blog posts, images, videos, etc. – and who will take responsibility for each task. Because we’re a remote company, obviously, we can’t all be in the same room. Working across various time zones also means synchronous meetings aren’t always possible. Since we run this process every month, we all know our established roles so we move straight to posting our deliverables.

A simplified version goes something like this:

- The marketing team (Contributors) post ideas, request days off, and other details into our sprint planning Slack channel.

- The Content Editor (Driver) collects all of this (providing gentle reminders when needed) and creates a loose plan for the upcoming month.

- The entire team (Contributors, Driver, Approver) review the plan, provide feedback, and make any necessary adjustments.

- The Content Team Manager (Approver) signs off on the plan.

- The outreach team (Informed) is notified.

By following this process, we’re able to solidify our schedule efficiently and easily.

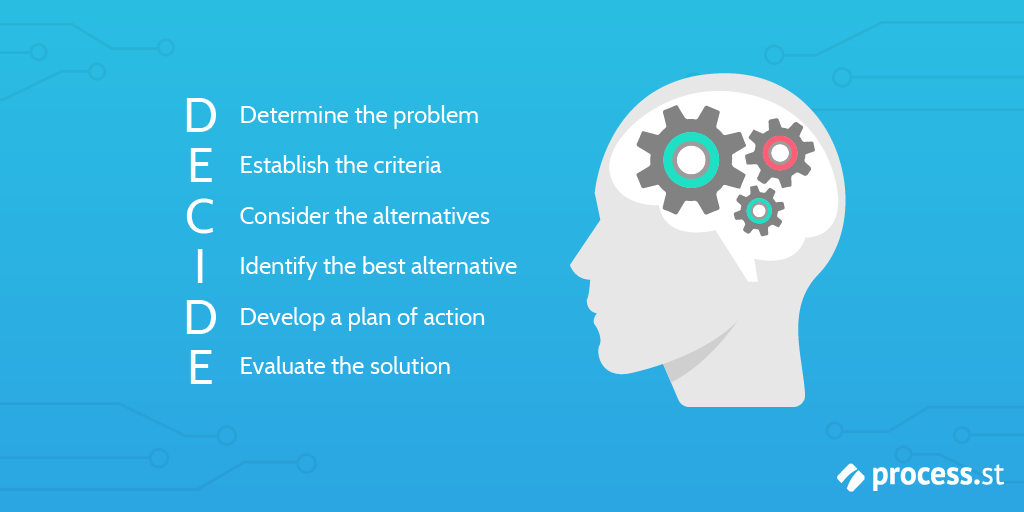

DSS #2: DECIDE

DECIDE is a popular framework used for academic research, but it has a wide range of applications across industries from healthcare to finance.

As with any system, everyone has a slightly different version of DECIDE that works for them. A good general-purpose version, though, is the one developed by Professor Kristina L Guo. She developed her version for healthcare workers, but the same principles can be applied to any business – or personal – decision you need to make.

The DECIDE DSS in action

Working from home gave me the luxury of using a quirky, antique writing desk for all my daily tasks. I love that desk, and for nearly a year I struggled to balance numerous notebooks, devices, monitors, and other essential items within a two-by-two area.

It was chaotic, to say the least. Given that I spend most of my time at my desk, how do I make sure I choose the right one? Let’s DECIDE.

Determine the problem

My current desk is too small for my needs.

Establish the criteria

It needs to be big enough for my computer, second monitor, and printer, plus many, many research materials and notebooks. My office space is at a premium, though, so it can’t be longer than 62 inches. An L-shaped design would be best.

Consider the alternatives

- A £150 L-shaped workstation made of two separate sections. It also has two shelves beneath the desk and a built-in monitor stand on the left. This would have me facing a window. (48×40 inches)

- A £122 L-shaped gaming desk made of one continuous surface. It comes with two lower shelves and a monitor stand situated on the right side. This would have me facing a wall, but with the option to work in the center diagonal. I like diagonals. (31×38 inches)

- A £129 L-shaped workstation with hutch shelving above the desk. (52×47 inches)

Identify the best alternative

While the third option is slightly bigger than I wanted, I prefer reaching up to shelves rather than fussing with them under the desk. It’s also slightly similar to Option #2 in that I have full flexibility about how I sit, plus it’s made of more solid materials than #2. It’s cheaper (with more) than #1.

Develop a plan of action

- Order the desk.

- Remove and rearrange current furniture to make room for the desk.

- Put the desk together when it arrives.

Evaluate the solution

I’ll try to complete the process with as little disruption to my workflow as possible, and assess whether there is enough space for my workstation as well as determine if there are additional pieces (such as a monitor stand) that I might want.

Simple.

DSS #3: The Ladder of Inference

This framework is actually more of a pre-decision system than a DSS. The Ladder of Inference focuses on fully understanding the situation before you act. This is often the most important – and often bypassed – part of making a decision.

We’ve all been in a situation where a solution or alternative seemed very obvious, but someone else either didn’t see it or didn’t agree with it. For the most part, we feel that our conclusions are the obvious one – and they are, to us.

Not only do we all process data differently, sometimes we aren’t even processing the same data. This means that it’s easy for each of us to come to a different conclusion, or decide that another conclusion is obviously wrong while ours is obviously right.

The Ladder of Inference is designed to address that unconscious presumption and force you to view your solution from a different perspective.

For the Ladder to work, though, it’s vital that you follow each rung of the ladder without skipping one. (This basically leads you right back to your usual patterns of thinking.)

The rungs of the Ladder of Inference are:

- Available data: All of the directly observable data that surrounds us on a daily basis: tone of voice, statistical reports, etc.

- Select data: Often we decide which data gets our attention unconsciously. This step is about consciously selecting from the available data.

- Paraphrase data: Put in your own words what is being said or done. This will help in interpreting the meaning and overall understanding.

- Name what is happening: This step identifies the situation with a general category, allowing you to contextualize where it fits into your previous experience.

- Explain what is happening: This is similar to the previous step, but it requires more detail. You may also make a positive or negative evaluation depending on your value system.

- Decide what to do: Based on your explanation, previous experience, and available options, decide which course of action is the best way to respond.

The Ladder of Inference in action

So my new desk arrived quickly, but I still needed to put it together. The steps are relatively easy to follow until it comes to attaching the two desk sections together. For whatever reason, I can’t line the two pieces up properly.

What is the available data?

Each step in the assembly process has been completed exactly as it is in the instructions.

What data have I selected?

I was sent faulty parts. Now I’ll have to return the desk, wait for a replacement, and figure out how to work for an unspecified amount of time without a workstation. This is a disaster and I never should have purchased the new desk in the first place.

Paraphrase the data.

While I’m pretty sure I followed the instructions, I can’t complete the last step in assembling the desk. My presumption is that I wasn’t sent the right parts.

Explain what is happening.

I’m frustrated and thinking emotionally because I’ve already put a lot of work into preparing and assembling the desk to end up without a finished product. It feels like I’m in a worse situation than I was in before, but I know there are ways to resolve the situation:

- I can contact the seller and request a replacement.

- I can return the desk for a refund and go back to using my old desk.

- I can recheck my work to see if I’ve missed something or made a mistake.

Decide what to do.

If I contact the seller and request a replacement, my experience tells me that they will probably try to fix my problem quickly. However, I would still need to wait for the replacement parts to arrive and hope this was the right solution while not having a usable workstation. This is not ideal.

The second possibility has the same problem. I would also have to disassemble, repack, and arrange for a courier to pick up of the new desk before putting my old workstation back together.

Both of these options will take extra time away from my work hours and potentially delay progress on the projects I’m currently working on.

The third option is an action I can take immediately. If it turns out I’ve made a mistake, I can fix it quickly and get on with my work. If it turns out I haven’t made a mistake, I can then choose either option 1 or option 2 without costing much time, plus having the advantage of being able to provide the seller with specific details about the problem. I decide to do this first, discover I accidentally used the wrong screw in one piece, and, once replaced, the desk sections line up perfectly.

The main advantage of this approach is that it prevents falling into what’s known as a recursive loop – only selecting data that supports our existing assumptions.

A good DSS is one that preempts those gut-feeling decisions. These frameworks are, essentially, designed to make you stop and assess before you make a decision. If I’d stuck with my initial emotional reaction, I would have unnecessarily added more obstacles to my day, wasted a sizable chunk of time, and still not had an appropriate workstation for my needs. By taking time to properly assess all the available data, however, I was able to develop a logical course of action that was easy to implement.

The framework best suited to your needs may be more complex, more simple, or a hybrid of multiple frameworks.

For an incredibly simple example, never make a decision in the moment. Personally, if possible, I like to give it a day before finalizing a choice. Obviously, timeframes don’t always allow for that, but you can almost always afford 5 minutes. While you may not get every detail you’d like, you can still process a lot of information in 5 minutes. At the very least, you’ll be better informed than you were 5 minutes ago.

DACI vs DECIDE: What’s your number one decision-making system?

Leks Drakos

Leks Drakos, Ph.D. is a rogue academic with a PhD from the University of Kent (Paris and Canterbury). Research interests include HR, DEIA, contemporary culture, post-apocalyptica, and monster studies. Twitter: @leksikality [he/him]