We talk a lot about business processes here on Process Street, but today we’re going to do things a little differently. Instead of waxing lyrical about business efficiency, I’m going to show how surgical checklists have evolved over history, and how they continue to save lives today.

From prehistoric humans poking each other with sticks and rocks, to the Ancient Greeks, the discovery of germs and antiseptics, up to modern day medical marvels, surgical procedures make a great case for why documented checklists are vital for continued success.

Not only that, but by looking at how major theoretical and technological breakthroughs have affected surgical checklists, we can better show why documenting and maintaining your processes isn’t as hard as you might think.

Alternatively, if you’re just interested in medical history, stick around for the ride – I’ll be making this interesting for all.

The first surgical checklists amounted to “drill a hole” (5th Millennium BC onwards)

One of the earliest known surgical practices that we have archaeological evidence for was trepanation – the practice of drilling a hole into the patient’s skull. The oldest example of this known comes from a discovery in Azerbaijan and is (supposedly) dated back to the 5th Millennium BC.

While we don’t know the exact reason this was carried out, one prominent theory is that this was done as a means to release evil spirits (which were probably used to explain headaches, seizures, and so on). Another, more compelling (if outlandish) theory is that trepanation was performed to attempt to revive the person from “death”.

Neolithic humans lived in a hunter-based society, but they weren’t stupid. In his paper “Possible reasons for Neolithic skull trephining”, Dr. Plinio Prioreschi noted that man would have noticed that certain head injuries resulted in “death” (eg, concussions or even comas). However, after a certain period of time some of these “dead” would wake up and return as “undying” beings.

Knowing this, and knowing that many times this was caused by light head injuries, man may have attempted to use trepanation to bring a “dead” member of society back to “life”. By making a hole in the skull, this would have allowed bad spirits to leave or good spirits to enter – whichever was considered to be the result of this “undying” event.

This is also supported by the presence of skulls which show the wounds to have healed partially, meaning that the person having the hole drilled sometimes survived. Some even suggest that the survival rate of trepanation was up to 78% in time periods and locations such as Late Iron Age Switzerland.

In other words, one of the earliest surgical processes can be theoretically broken down to the following:

- The process begins when a person “dies” from a head injury

- Check that there’s no immediate danger

- Try waking them up

- Assess whether the person is worth attempting to revive

- If so, gather the appropriate tool (something sharp)

- Scrape a small portion of the skull away to try to revive the person

Admittedly, I just made up that process, but based on the evidence provided, it’s as good a starting point as any. This is a rough draft which uses what was known at the time to try and solve a problem.

While I doubt that Neolithic man ran around using checklists to make sure they were consistently performing the same operation on all patients, it serves as the foundation for later innovation, much in the same way that processes in general don’t have to be comprehensive when first documented.

When creating the first version of your processes, the act of documenting it is arguably more important than the actual content. It pays to make sure that it’s as accurate as possible to the workflow you actually follow, but as long as that’s the case then you’ll always have room to improve upon and expand it later down the line.

Plus, having a set process lets you more easily integrate new ideas and technology into your practices. Speaking of which…

Humoral theory and the Hippocratic Oath show the need for process improvement and re-engineering (5th century BC)

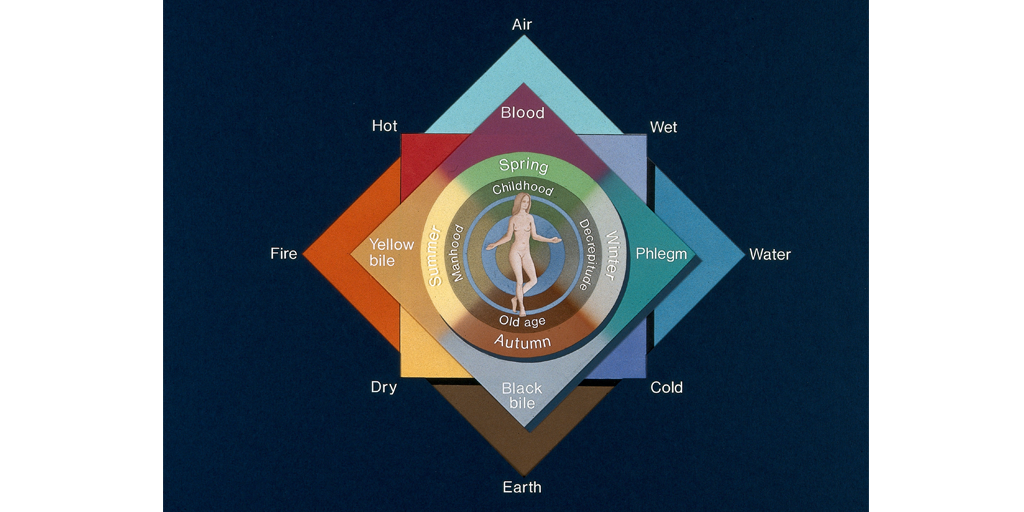

Skipping forward to the Ancient Greeks (and a little beyond), the predominant idea behind medical practices was now that of the four humors. The theory is generally attributed to Hippocrates, although it was also shaped by later figures such as Galen, and influenced medicine for hundreds of years to come.

The humors represented the four elements of air, water, earth, and fire, and consisted of blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile respectively (although blood was thought to contain all four elements). Illnesses and maladies were thought to be due to an imbalance of the humors, and thus balancing them once more would cure the patient.

This was achieved by each of the four humors and liquids also being linked to specific organs and temperaments. Now, bear with me here, I promise this is relevant to our investigations into surgical processes.

To summarize:

- Air was linked to blood, which was thought to be produced by the liver, caused a sanguine (enthusiastic, social) personality, was more prevalent in infants and springtime, and was encouraged by moist, warm foods

- Fire was linked to yellow bile, produced by the spleen, caused choleric (short-tempered and irritable) personalities, was prevalent in summertime and youth, and was encouraged by warm, dry foods

- Earth was linked to black bile, produced by the gallbladder, caused melancholic (analytical, quiet) personalities, was prevalent in autumn and adults, and was encouraged by cold, dry foods

- Water was linked to phlegm (which didn’t mean “snotty mucus” back then), produced by the brain and lungs, caused phlegmatic (relaxed and peaceful) personalities, was prevalent in winter and the elderly, and was encouraged by moist, cold foods

Also from Hippocrates came the Hippocratic Oath, which is still in use (albeit modified) today. While the specifics have changed, this was the oath which a physician had to take in order to be trained, and essentially made them swear to help the sick without any aim to do harm or injury.

The Hippocratic Oath, combined with the dangers still associated with surgery (despite now having iron tools, infection was a high risk), meant that surgery was often a last resort for physicians. This, along with the humoral theory, resulted in most cases being treated with a heavier focus on methods like bloodletting, purging, diuresis, and dietary recommendations instead of outright surgery.

The amount of blood that was let would correspond with the severity of the injury, and different locations on the body were thought to affect different organs or humors. Thus, a general physician’s checklist at the time (although, again, this is my own general summary) might have looked like this:

- The process begins when faced with a patient

- The afflicted area (if known) is checked and assessed for the type of injury

- If the injury is physical (eg, a broken bone) and severe, surgery may be performed

- If the injury isn’t immediately life-threatening or physical, an assessment will take place to judge the patient’s humoral balance

- Through examining their temperament, the type of affliction, the level of associated pain, and other such elements, the humoral balance is calculated

- Depending on the humor in excess, the patient will be given the appropriate treatment

- If blood is overabundant it will be let from a location relating to the organ seen to be causing problems (eg, veins in the right hand for the liver, the left hand for the spleen). More is let if the condition is severe.

- Prescribe further treatment if required (eg, purging)

- Dietary supplements are recommended to help boost the patient’s lacking humors

So, while it is a rather large time leap, by comparing this to the previous surgical process we can see that the entire thing has either been incrementally improved or straight up re-engineered according to the new humoral school of thought.

Once again, I won’t pretend that this is fool-proof, comprehensive in any way, or even wholly accurate, but in terms of the evolution of surgical processes, it’s certainly a fascinating leap.

Processes provide a good framework to go off, and let you see exactly what your methods are, how to repeat your successes, and where you can improve your practices. While they might be lacking when you initially document them (eg, trepanning), having them set out at all lets you either improve them until they are sufficient or realize that it’s better to scrap them entirely and start building from the ground-up.

Anesthesia’s development completely changed surgery, but not necessarily the processes (1840s)

Anesthetics completely changed the face of surgery. With the use of ether (and chloroform soon after) starting in 1846, patients were now able to be knocked unconscious while operations were performed that would otherwise be awkward to perform and excruciating to endure.

Forms of anesthesia (herbs, oils, alcohol, opium, etc) were certainly in use before the 1840s, but they tended to be either ineffective to the point of being largely worthless or so effective that the patient died from an overdose. As such their use was limited at best, which put great pressure on surgeons.

The lack of effective pain relief meant that the prized skills of a surgeon were speed and accuracy. They distinguished themselves (and still do, to a certain degree) by being able to perform their duties quickly enough to limit the pain as much as possible. Speed was particularly important when carrying out amputations due to the trauma involved.

Beyond that, the lack of anesthesia (and the resulting time-sensitive nature of operations) limited surgeons to only carrying out certain procedures, such as removing external tumors, amputations, and trepanning. Yes, people were still getting holes drilled in their heads.

The use of ether (shortly thereafter replaced by chloroform) in 1846 allowed surgeons to reliably knock out their patients, which allowed more care to be taken and more internal and in-depth operations to be performed. Speed and accuracy were still important for surgeons, but anesthetics truly allowed the skill of a surgeon to shine, as the patient would remain still.

So, how does this relate to surgical processes?

It doesn’t. Well, not entirely.

The invention of reliable (and, eventually, safe) anesthetic didn’t necessarily alter surgical processes, other than perhaps no longer needing you to tie down the patient. The only reliable thing this added was to assess whether anesthetic was necessary, and if so, to administer the appropriate amount.

Instead, this development allowed surgery as a field to advance into more complex and internal operations, along with drastically increasing the comfort of patients.

In other words, huge breakthroughs in a given field don’t necessarily mean that all of your existing processes have to be scrapped and re-built. Take into account the nature of the development and how this will actually affect your current processes, and then assess what changes need to be made based on that.

Germ theory, antisepsis, and asepsis show why following processes is important (1860s)

After Louis Pasteur provided proof of germ theory (the theory that some diseases were caused by germs) in the early 1860s, the race was on to find a way to deal with and nullify this newfound threat. Infections post-surgery were rampant and the cause of a significant number of deaths even after successful operations.

Remember; until this point there was no concept of contamination in surgical theaters, meaning that clothes and tools would be used for several patients (potentially without being cleaned) and sterilization simply didn’t exist. Even if a scalpel was rinsed off between operations, the lack of sterile techniques meant that germs were often spread between patients by the very people attempting to cure them.

After reading Pasteur’s findings in 1865, Joseph Lister thought to use carbolic acid to kill off any germs around open wounds, and shortly thereafter devised a machine which spread a fine mist of carbolic acid around the operating theater during his operations. While he was wrong about most germs being airborne, his methods caused his patients’ death rates to plummet from 45.7% down to 15%.

Let that sink in for a second – even without sterilizing his equipment properly, by introducing a single simple practice (dusting the room and wound periodically with carbolic acid, and wrapping the wound in material soaked in it), Lister was able to save the lives of 30% more of the people he treated.

This is why it’s important to have set, documented processes for the tasks you perform. While it’s far from complex, the frequency and consistency required to correctly perform this is incredibly difficult to achieve. Not to mention that the penalties for failing to do it are severe.

However, to truly appreciate the power of having regular, normalized, repeatable processes for the simplest of tasks, we need to turn our attention to a Hungarian physician of the time…

Semmelweis, The Checklist Manifesto, and the WHO bring us to the present day’s surgical processes (1840 – 2017+)

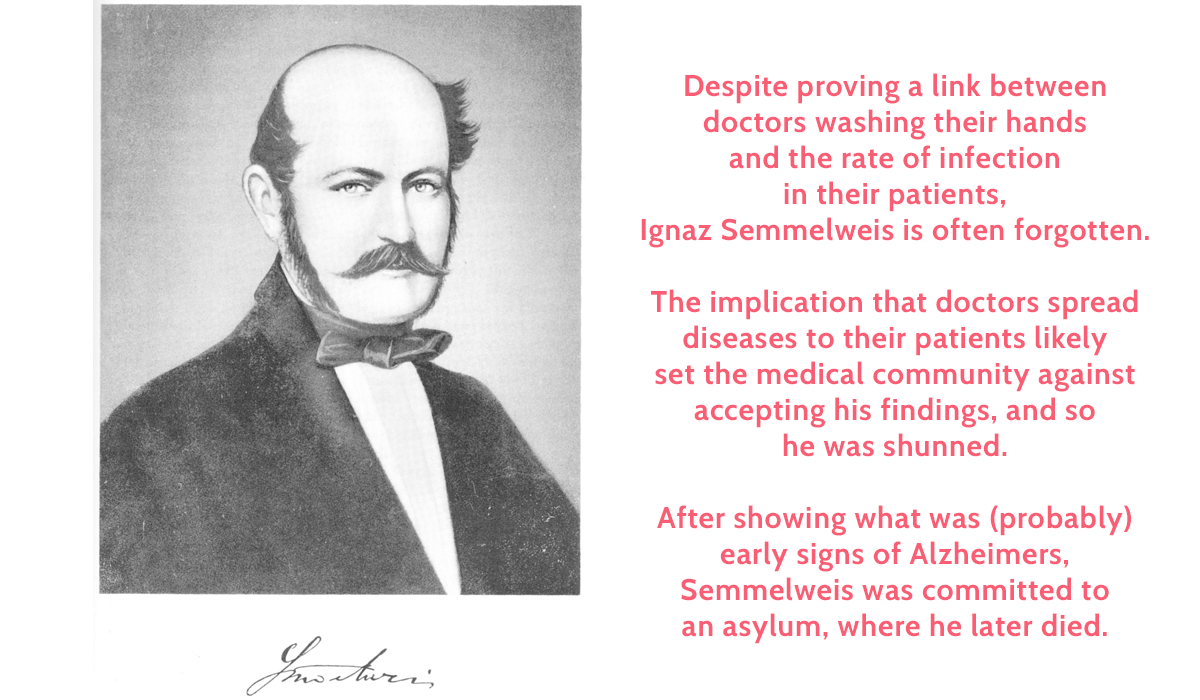

Ignaz Semmelweis was a Hungarian physician in 1846 who found himself studying deaths in maternity wards, especially due to childbed fever. Remember that this was before Pasteur had proven germ theory, and long before Lister showed that killing germs could prevent infection.

Semmelweis’ problem was that the death rate in maternity wards ran by doctors was much higher than those run by midwives, but for all intents and purposes, patients were treated identically across both. Something had to be different, and by figuring out what, Semmelweis wanted to drastically reduce deaths in the doctor-ran clinics.

After ruling out several factors and becoming frustrated with failed experiments, he realized that the only difference between clinics was that the doctors would also perform autopsies on those who died from the fever.

Thus, Semmelweis had a brainwave.

He theorized that the doctors’ contact with bodies known to have the infection was contaminating them, and that going on to have contact with living patients without cleaning themselves first would transfer the fever to the living.

To test this theory, Semmelweis simply asked the doctors to wash their hands when moving from patient to patient, and especially when moving from autopsies to examinations of living people. This resulted in death rates due to childbed fever in clinics run by doctors plummeting from 12% to 2%.

Now, although these findings were fantastic, and would have provided simple, yet powerful changes to surgical checklists from that point onwards, there’s a reason you’ve probably never heard of Semmelweis before.

While their precise motivation isn’t clear, Semmelweis’ colleagues refused to accept his findings, and thus his teachings were largely ignored. This is possibly due to the implication the theory had of physicians being responsible for the infection and deaths of their patients, but either way, hospitals even today struggle to reliably enforce the simple policy of washing hands to save lives.

How do I know that even modern hospitals struggle with just washing their hands reliably? Well, I’m glad you asked.

The Checklist Manifesto is a fantastic book by Atul Gawande, showing the importance and effect of having documented, repeatable processes with real human consequences.

From remembering to wash hands before and after surgery, to properly sterilizing tools and preparing everything required for an operation before it’s needed, the power of just documenting and using “stupid little checklists” is truly amazing when applied to modern, measurable environments.

For example, here’s what happened after just one state (Michigan) rolled out checklists in their hospitals:

“In the Keystone Initiative’s first eighteen months, the hospitals saved an estimated $175,000,000 in costs and more than 1,500 lives. The successes have been sustained for almost four years—all because of a stupid little checklist.” – Atul Gawande, The Checklist (The New Yorker, December 2007)

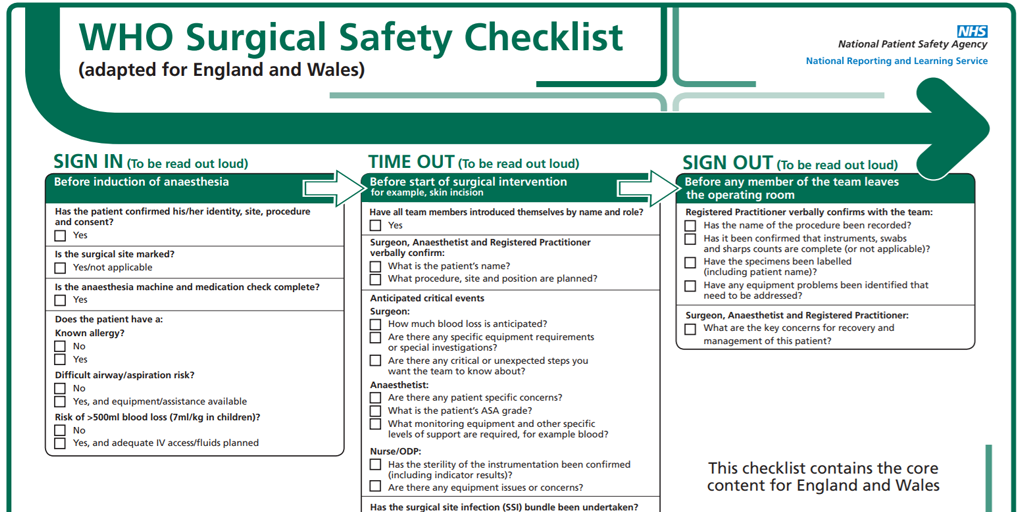

Thus, back in 2009, the World Health Organization (WHO) produced an official and universal surgical safety checklist. It isn’t hugely complex, but its simplicity allows it to be used across pretty much any and all surgical procedures, meaning that filling it out can become part of the regular routine of medical professionals.

Plus, we know that this simple checklist has drastic real-world effects just by reminding people of the basic things they have to reliably do before, during, and after each surgery. Hospitals using the checklist were shown to have 38% lower death rates for emergency abdominal surgeries within 30 days of the operation.

Consistency is vital in surgical checklists, because lives aren’t just margins for error

When you write about processes as often as we do here on the Process Street blog it can be tempting to waffle on about the importance of processes in technical terms. However, every so often it’s good to remember why processes are needed at all by looking at the human elements behind those workflows.

In business, a documented process allows you to reliably, effectively, and efficiently complete your tasks no matter what skill level you’re at. Business process management is a means to deploying and monitoring them effectively. The aim of process improvement is often to simply reduce the number of “errors” in your results.

In medicine, those “errors” are more than statistics – they’re lives.

Medicine and surgery involve incredibly complex processes, and the price of getting any step wrong (or, worse yet, forgetting to complete a step before moving on) can mean the literal death of your patient. The odds are truly stacked against you, and the stakes are almost never higher for if you fail.

Yet still, day in and day out, these medical and surgical checklists and procedures are carried out to near perfection, thus saving the lives of countless patients and making many more rest easy in the knowledge of their diagnosis.

After all, modern medicine is capable of utterly amazing feats which even Pasteur and Semmelweis would find astounding, let alone Hippocrates or prehistoric man. So, to finish off, I’d like to go over another example of one such miracle from Atul Gawande.

When a three-year-old girl fell through an icy fishpond in a small Austrian town in the Alps, she was lost for almost thirty minutes before her parents discovered her at the bottom. In total, she was medically dead for two hours before they were able to restart her heart (no heart or brain activity).

What followed was a gruesome list of medical and surgical procedures, any one of which could have resulted in catastrophe for this young girl. Yet, despite all the odds, there was light at the end of the tunnel.

One week later, she awoke from a coma. After two weeks she was living at home again. Within two years (and after extensive therapy) the partial paralysis and slurred speech she suffered from as a result of the accident were nowhere to be seen.

“What makes her recovery astounding isn’t just the idea that someone could come back from two hours in a state that would once have been considered death. It’s also the idea that a group of people in an ordinary hospital could do something so enormously complex.

To save this one child, scores of people had to carry out thousands of steps correctly… The degree of difficulty in any one of these steps is substantial. Then you must add the difficulties of orchestrating them in the right sequence, with nothing dropped, leaving some room for improvisation, but not too much…” – Atul Gawande, The Checklist (The New Yorker, December 2007)

In other words, processes don’t just let us do our jobs correctly. In this case they literally let us achieve what would otherwise be impossible and save the life of a young girl who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.

What argument for processes is better than that?

What are the most important processes you know of? I’d love to hear from you in the comments, and also what you think to this slightly different take on our regular content!

Workflows

Workflows Projects

Projects Data Sets

Data Sets Forms

Forms Pages

Pages Automations

Automations Analytics

Analytics Apps

Apps Integrations

Integrations

Property management

Property management

Human resources

Human resources

Customer management

Customer management

Information technology

Information technology

Ben Mulholland

Ben Mulholland is an Editor at Process Street, and winds down with a casual article or two on Mulholland Writing. Find him on Twitter here.