Look up the history of any modern technology, and you’re taken on a quick-fire tour of antiques, innovations, failures, successes, bubbles, booms, and busts.

Unlike the history of the Roman Empire or Greek poetry, software history is almost immeasurably short.

It’s rich and it’s exciting, but it’s also full of strange developments. Developments that never really went anywhere, but serve as warnings to organizations of the kinds of flops to avoid.

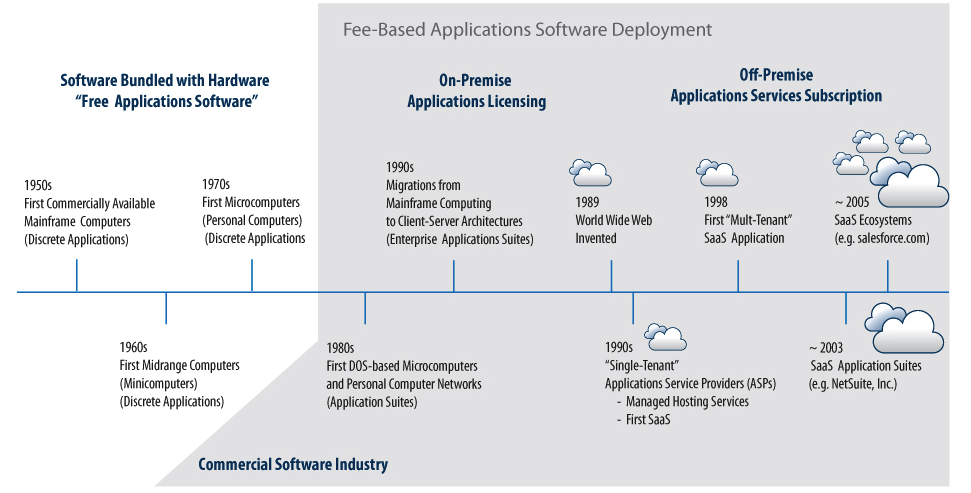

New terminology and seemingly revolutionary inventions have cropped up every single year since the 1960s, but by now most of what formed the foundations for today’s software market is obsolete.

In today’s world, the majority of businesses and consumers use software-as-a-service (SaaS). If you define SaaS an application that can be accessed through a web browser and is managed and hosted by a third-party, then Facebook, Snapchat, Google — and many things that most people would just call ‘websites’ — are SaaS products.

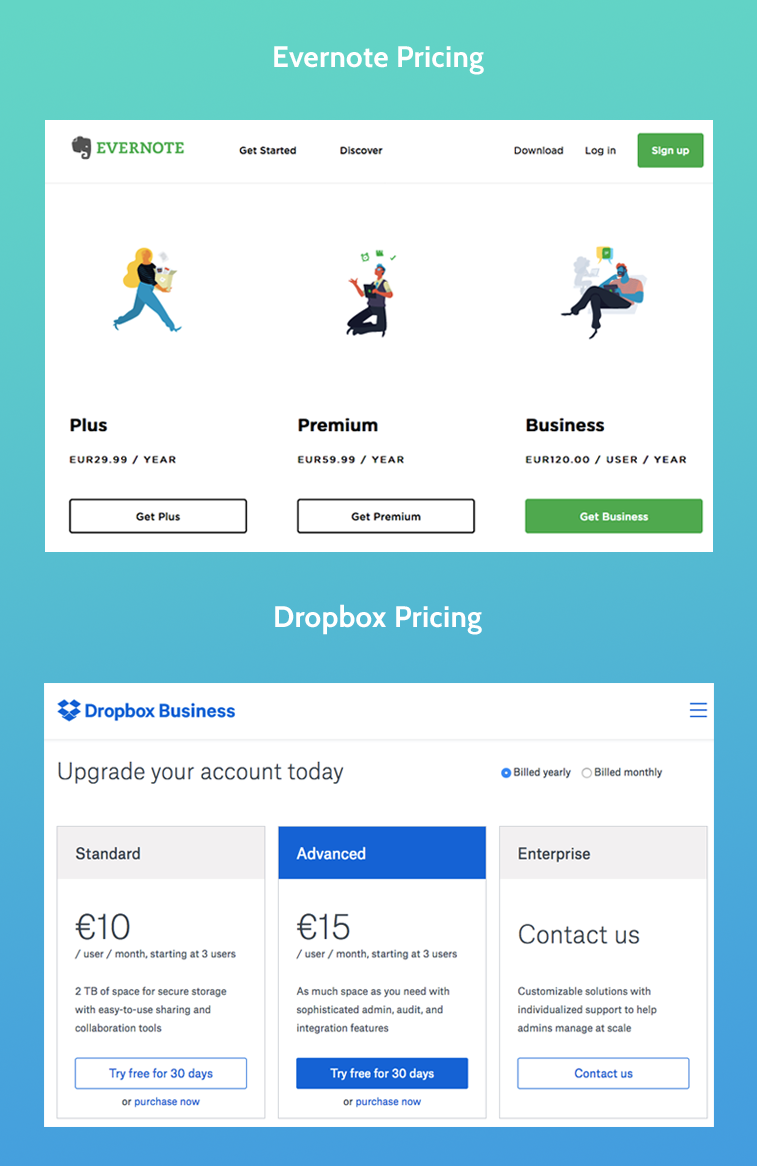

In a business sense, SaaS is both a way for customers to access software over the internet, and a revenue model. SaaS is most commonly monetized by providing access to users for a monthly fee. You might’ve seen that on the pricing pages of Evernote, or Dropbox.

Usually histories have some wacky starting point that you’d never have expected, and SaaS is no different.

IBM: a 1960s SaaS company

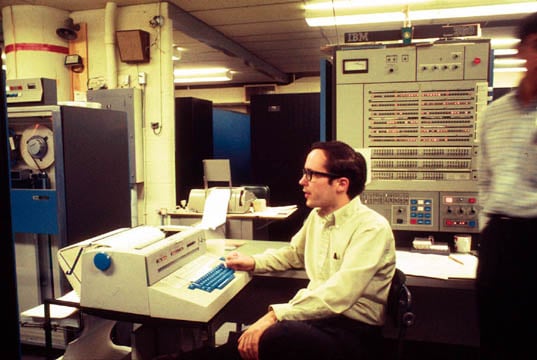

The closest thing you can get to a visualization of IBM’s 60s SaaS is this:

That’s the IBM 360 Model 67. It’s from 1965, and IBM used these and the computers they developed over the next decade to provide processing power to organizations like banks and government offices.

To give you an idea of the power these computers had, the most advanced IBM 360 (the Duplex) had a 2mb RAM, and, even over a decade later in 1980, hard drive space cost almost $200,000 for a gigabyte. Buying your own machines simply wasn’t an option when you could rent power and space from a dedicated provider for a fraction of the price. The service was called time-sharing.

“Two decades earlier, an IBM computer often cost as much as $9 million and required an air-conditioned quarter-acre of space and a staff of 60 people to keep it fully loaded with instructions. The new IBM PC could not only process information faster than those earlier machines but it could hook up to the home TV set, play games, process text and harbor more words than a fat cookbook.” — IBM Archives

Computers were still huge and weak by today’s standards, but this development now made them capable of being situated or having data and power hosted in a different physical location to the one they were being used in.

In the 1960s, organizations were focused on developing their own software using the resources of mainframe providers like IBM. While this doesn’t make it software as a service as such, time-sharing is an early location-independent development in enterprise computing that can be seen as a key step towards SaaS.

1970s & 80s: the growth of pre-SaaS architecture

Time-sharing remained popular throughout the 1970s, but as the personal computer market was starting to get on its feet, businesses found that it was financially viable to give each employee their own computer with its own hard-drive and on-premises applications.

Since smaller, more powerful computers like the IBM PC eliminated the need for mainframe behemoths and time-sharing, the surge of SaaS progression took a bit of a break while it was all the rage to have your own disk space and office applications.

However, it during the 80s that the first ever CRM was developed by Pat Sullivan and Mike Muhney in Texas. ACT! was a DOS CRM marketed as a digital Rolodex that allowed businesses to store contact details and sell more effectively to their audiences.

Other early SaaS examples include Great Plains, (which went on to be acquired by Microsoft and turned into Microsoft Dynamics) and Concur.

Applications weren’t graphical at this time. They had minimalist text-based interfaces, and since software didn’t need to handle complex images or Big Data, that didn’t matter.

During the 1990s, graphical SaaS came to the forefront lead by the company that went on to develop the most successful SaaS product in the world.

1990s: the dot com boom

The complexity of software increased at a rate faster than the hardware’s capability of handling it, especially for big businesses running hundreds of thousands of computers. Managing systems and applications of employee’s personal computers became a tangled mess, with IT teams reportedly scrambling in poor work environments to get the inefficient networks up and running.

These technological developments meant that operating systems became larger while hard drive space was still expensive, and businesses needed a way to get the applications on multiple PCs without filling up too much space.

The best way to do that? Exactly the same way they did it in the 1960s: host the data on somebody else’s computer.

Software used to be provided to companies on disks, along with licenses that gave the buyer access to some degree of tech support, and a limited amount of updates.

Buyers had the safety of knowing that their software needs were being looked after, but it had its distinct downsides. There were notoriously restrictive contracts, vendors pricing packages as they pleased, and software companies forcing customers to pay hefty upgrade charges whenever a new version came out. Add to this the fact that tech support and maintenance cost extra, and you’ve got a high barrier to entry for companies that could benefit from software but couldn’t possibly afford it.

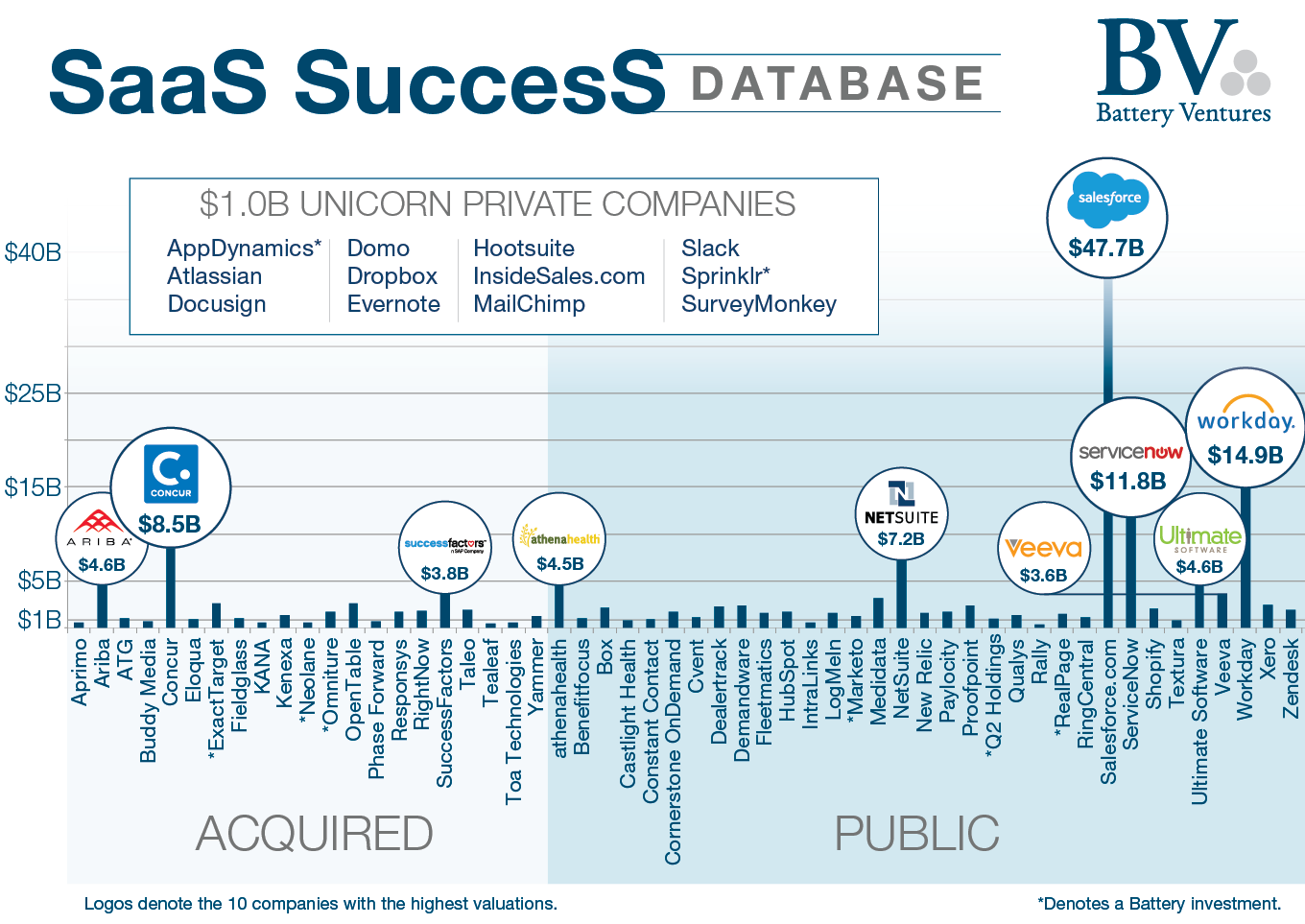

In the 1990s, today’s giants established themselves. Intacct (who we featured recently in our archive of sales emails), NetSuite, and, of course, Salesforce.

But, before we get into that, it’s worth going over one of software histories most irrelevant footnotes: ASP.

The rise (and cataclysmic fall) of ASP

Application Service Providers (ASP) is both software that was being created in parallel to SaaS and a pre-cursor. While it was a necessary stepping stone, ASP’s inefficiencies made it more useful in theory than in practice, especially when implemented in big businesses. The differences are minute and confusing, and, while many software experts try to verbosely articulate them

Writing on ASP as part of SaaS history, Steven J Vaughan-Nichols describes a key issue with the software:

“Most of the ASP applications were version 1.0 quality software in a universe where the desktop versions were at version 3.0. There was no good reason for a business to make a monthly financial commitment for an application that did less than the established software your business had already paid for.”

Rick Chapman, writing on Softletter, a long-running software authority site, condenses the issue neatly:

“The difference between SaaS and ASPs is that SaaS companies make money and ASPs didn’t.”

Let’s put it this way: with ASP, the vendor had to set up your login and environment manually from their end. With SaaS, it was all self-service. You can imagine why ASP collapsed under its own weight and SaaS flourished despite enterprise compliance issues and worries about the stability.

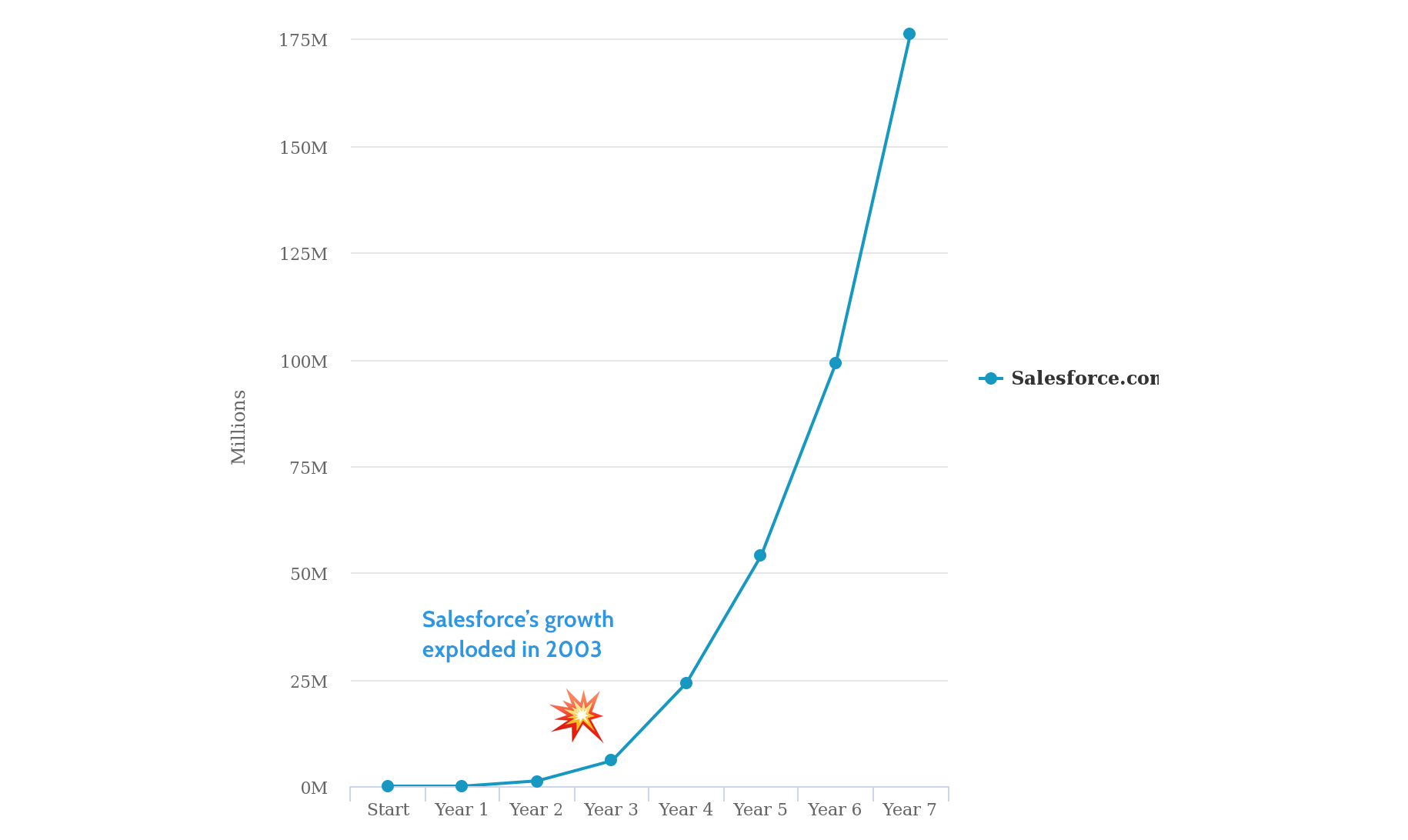

SaaS vendors were successful enough by the early 2000s to keep the market afloat ever since, and Salesforce is a prime example.

Salesforce: the first pure SaaS superstar

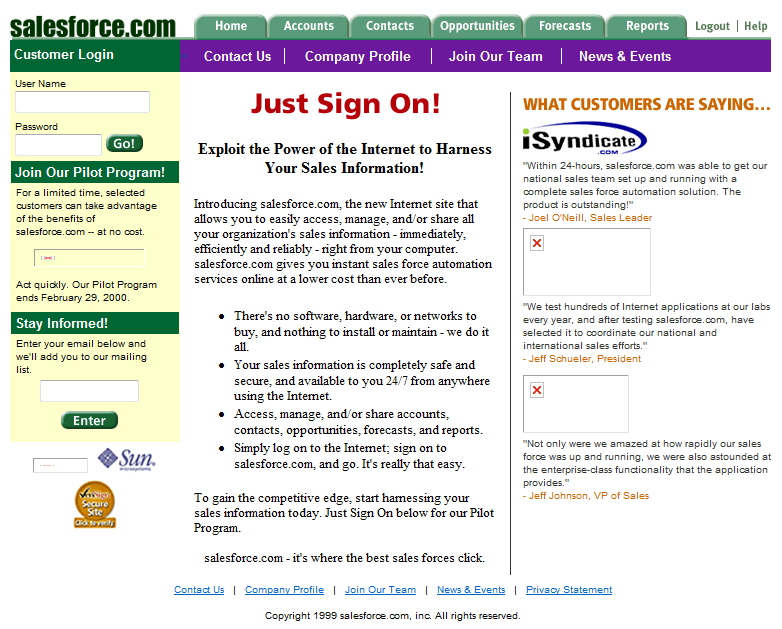

Salesforce had the SaaS vision right from the start.

Unlike Concur, Microsoft, Oracle, and Lotus, Salesforce never messed around with physical products or ASP infrastructure — its app was delivered purely over the internet, with access in the browser. Going all in on SaaS gave Salesforce a massive head start, setting them up to become the single most valuable SaaS company ever founded.

Its “No Software” mantra and attitude was controversial, but within the space of one year Salesforce had scaled up to the point where its employees were working full time in hallways and conference rooms because its 8,000 ft office (originally filled with only 10 employees) couldn’t handle the growth.

The SaaS ubiquity of 2010

With Salesforce leading the way, SaaS was finally a proven business model. That forced incumbents like Sage and Oracle to deliver a SaaS version of their products just to level the playing field, and it made SaaS the only option for startups who could see that the future of software wasn’t in cases of 10 disks and a license key, but in the cloud.

IDC estimates that the enterprise SaaS market will be worth $50.8B by the end of 2018, up from $22.6B in 2013.

AngelList lists over 12,000 SaaS startups in its database as of August 2017, and while the exact number of established SaaS companies is unclear, it’s predicted to be between 9,000 and 12,000 with an average valuation of $4.4m.

Blurred lines, and the commercialization of SaaS

At the start of this article, I mentioned how Facebook, Twitter, and other things that we just consider to be websites are SaaS products. By defining SaaS in such broad strokes, it shows that the term is becoming dated, hard to pinpoint, and representative of a massive restructuring of the internet.

There’s basically no difference between SaaS and the internet because the internet is simply a place where HTML, CSS and JavaScript come together in any form or combination to provide you with a page, service, tool, etc..

Netflix, which started out as a mail order Blockbuster competitor, is a SaaS product that I use on my TV along with its local competitor. I’ve got a bunch of SaaS installed on my phone, and a lot those apps are just a wrapped version of a web app distributed through the app store.

JavaScript environments like Node and the improvement of powerful, accessible database languages that can run on cost-efficient Amazon servers means that SaaS can be developed and deployed by people, not just enterprises. Look at the amount of SaaS startups on AngelList, and look outside of the business world at the thousands of passionate people enthusing about SaaS products on Product Hunt every single day.

In fact, with Estonia’s e-Residency program and its plans to build the economy on a local blockchain currency, it could be said that Estonia is becoming the first SaaS country. The history of SaaS is coming to an end while merging into the grander history of the internet and the world at large.

Benjamin Brandall

Benjamin Brandall is a content marketer at Process Street.