What connects a 75% drop in infection rates, a 48% increase in home rebuilding speeds, and an extra 400 hungry families receiving the supplies they need to get by?

What connects a 75% drop in infection rates, a 48% increase in home rebuilding speeds, and an extra 400 hungry families receiving the supplies they need to get by?

Have you guessed yet?

That’s right. Effective process analysis and implementation. Specifically, the Toyota Production System process analysis and implementation.

In this article, we’re going to look at some of the heartwarming success stories of process implementation carried out by the Toyota team.

The human side of organizational systems demonstrate the importance and effectiveness of learning and understanding how to create continuous improvement in your processes.

Throughout these examples we’ll see a number of key Toyota concepts employed and how they worked in practice:

- genchi genbutu – to “go and see”, to embed yourself in the system and observe,

- kaizen – to employ ideas of continual improvement, making small iterative changes,

- muda – to identify waste, and to recognize that what constitutes waste is contingent on your situation.

From disaster relief to pediatric hospitals, the benefits of strong process analysis are clear for all to see.

Why process implementation?

Here at Process Street we publish articles which attempt to educate and inform readers on topics surrounding processes and organizational systems.

Some of these might be introductory guides intended to provide a simple entry point to business process management: What is Business Process Management? A Really Simple Introduction

Others might be analyses of semantics and the words we use to discuss process related concepts: Processes, Policies and Procedures: Important Distinctions to Systemize Your Business

Or we could be delving into the more technical mechanics of utilizing processes and systems within your business: BPMN Tutorial: Quick-Start Guide to Business Process Model and Notation

However, all this is for nothing if we cannot demonstrate that operating in this manner provides significant value. Throughout The Checklist Manifesto, our in-house bible, there is the tale of checklists being implemented in a hospital and the positive results that change generated. This short demonstration of the power of checklists powers the book’s forward trajectory and lends credence to its overall philosophy.

That’s why this post is going to be dedicated to the success stories of process implementation.

We’re going to look at the stories of 4 Toyota outreach programs where they attempted to take the knowledge they had gained from the production factory floor and use it for new positive causes.

Infections in 4 pediatric hospitals fell by 75%

The most recent of the Toyota Production System Support Center projects was a collaboration with four children’s hospitals in the US:

- Children’s Health in Dallas,

- Cook Children’s Hospital in Fort Worth, Texas,

- Children’s Hospital in Cincinnati, Ohio,

- and Children’s Hospital of Kings Daughter in Norfolk, Virginia

The problem these hospitals were all facing was the same.

The hospitals were all experiencing high levels of Central Line Associated Bloodstream Infections (CLABSIs). This occurs when a plastic tube is placed in a vein which goes directly to the heart. All the equipment was sterilized like for any other medical procedure, yet this routine action kept leading to infections.

According to a study published in the Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, approximately 250,000 CLABSIs occur annually at hospitals across the country. These infections are serious but often can be treated successfully. However, such countermeasures cost more than $6 billion annually, according to a study published in the Journal of Infusion Nursing.

The hospitals were struggling to deal with the issue and wanted to explore outside approaches to see if infection rates could be brought down.

This is where Toyota’s team came in.

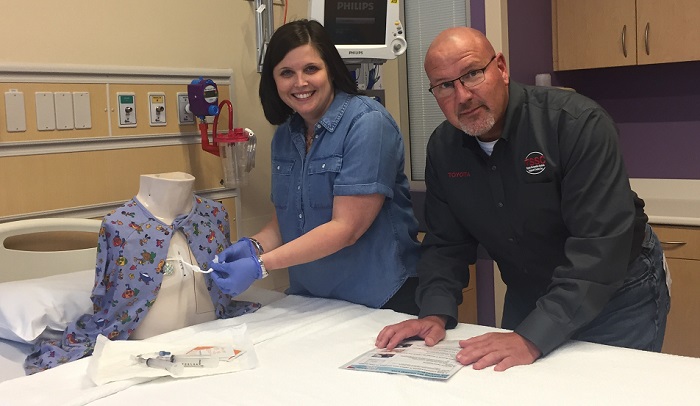

Their first working principle is one they refer to as genchi genbutu, which means “go and see”. Toyota sent their team to these hospitals to observe and monitor; looking for potential sources to the problem.

Their first working principle is one they refer to as genchi genbutu, which means “go and see”. Toyota sent their team to these hospitals to observe and monitor; looking for potential sources to the problem.

This tactic stresses the importance of involving yourself in the minutiae of the process and engaging with the way the process takes place in the real world; analyzing not just the documented process but the realized and embedded process.

Dickson spent time at each hospital observing and taking notes. That unbiased perspective proved to be the turning point. In each case, healthcare practitioners were following the proper steps to ensure they were germ free. But the rooms in which the children were being treated? That was a very different story.

Though steps were continually being taken to make sure the equipment had been sterilized properly, they were often placed down on surfaces which had not been as rigorously, nor as regularly, treated. Dickson reports:

“What they thought was the problem and what was actually the problem turned out to be very different things,” “There’s no way we would have figured it out if we hadn’t spent time at each site and talked with the nurses on the floor.”

The aim, once the problem had been diagnosed, was to begin to find an effective solution for this error. The solution couldn’t be a one time thing – it needed to be something replicable across all sites. The Toyota team, therefore looked to implement their standardization procedures in order to expand the process and eliminate the actions causing the contaminations.

The embedded nature of the Toyota approach helps to eliminate some of the imperfections surrounding standardized systems. The goals were clear, the participants were involved, and the systems were designed for practical use rather than mere documentation.

The embedded nature of the Toyota approach helps to eliminate some of the imperfections surrounding standardized systems. The goals were clear, the participants were involved, and the systems were designed for practical use rather than mere documentation.

If we take an extract of Carl Cargill’s Why Standardization Efforts Fail from the journal Standards (Volume 14, Issue 1), we can see how the approach has dodged some classic pitfalls:

The person actually creating the standards is working in an area of imperfect knowledge, high economic incentives, changing relationships, and often, short-range planning. The ostensible failure of a standard has to be examined … from the viewpoint of whether the participants achieved their goals from their participation in the standardization process.

The solution in the end was simple.

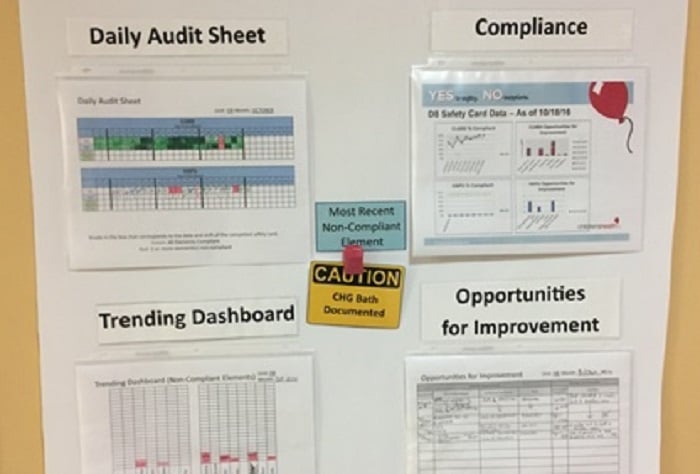

Toyota introduced:

- Sterile pads to act as barriers between surfaces and equipment

- Visual boards where they track their progress each day

- Morning standup meetings to discuss the previous day

- Regular auditing to catch problems as fast as possible

After one year, infections were down 75%. Process analysis and implementation has never felt so good!

After one year, infections were down 75%. Process analysis and implementation has never felt so good!

Home rebuild speeds after Hurricane Katrina increased 48%

In the wake of Hurricane Katrina, thousands of families were left without homes.

This was one of the biggest disasters faced by the modern United States.

Ten years later the rebuilding process was still ongoing. It was 2015 and the anniversary of Katrina had spurred the St Bernard Project to push even harder in their efforts to construct more homes for those displaced.

The non-profit had already rehoused 600 people in the St Bernard Parish by July 2015, but an estimated 5,000 families were still waiting on a return. The project was fielding 15-20 calls a week from homeowners seeking help.

It was clear that improvements needed to be made.

But what improvements? The project relied heavily on volunteers and increased funding wasn’t going to suddenly appear overnight. The team had to find a way to sustainably work within the parameters of what was available to them.

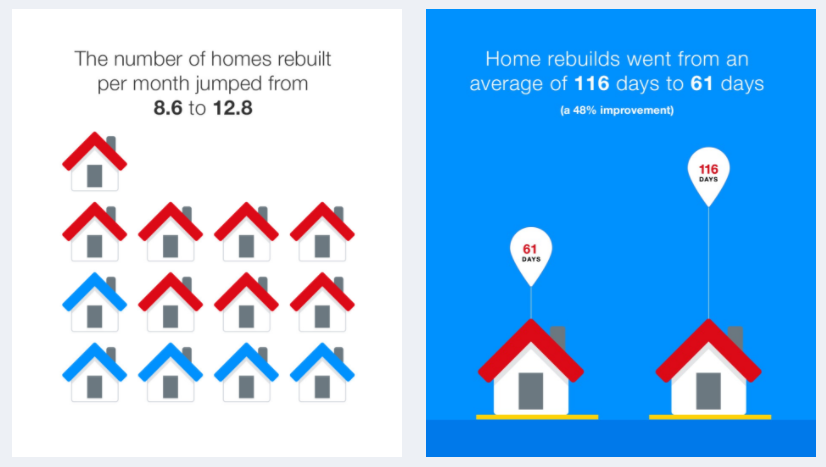

This means small iterative improvements and sharp focused analysis. For this, the Toyota team came in to assist.

The Toyota team focused on managing and deploying volunteers as effectively as possible to make the most out of the available labor. Added to this were further steps to improve and standardize storage of equipment and materials. These standardization methods made it easier to find items and utilize them. Each small increase in speed adds up to make an overall increase in productivity.

Toyota deployed their visual method of utilizing a whiteboard to manage projects. This allows everyone to see and understand the overall progress while also recognizing their role in the process.

Toyota deployed their visual method of utilizing a whiteboard to manage projects. This allows everyone to see and understand the overall progress while also recognizing their role in the process.

Further to this, the Toyota team created easy to understand and remember categorization systems to aid their storage of equipment. The step-ladders, for instance, were given individual names. These kind of small changes make communication easier and add to the iterative productivity gains.

In the end, the Toyota assistance lead to the number of homes being rebuilt each month jumping from 8.6 to 12.8 and the home rebuilds went from taking an average of 116 days to 61; a 48% improvement.

Through employing these organizational processes effectively, more families who had been waiting for a decade were able to be homed.

NY food bank can feed 400 more families in half the time

The Food Bank for New York City is the largest food bank in the United States and the largest anti-hunger charity in general. It feeds about 1.5 million people every year.

Many large businesses, particularly New York based businesses, make donations to the food bank. Toyota is no exception.

However, in 2013, Toyota decided to offer the food bank something different. It decided to provide consultancy. Toyota’s aim was to transplant its ethic of continual improvement, kaizen, into the operational structures and processes of the charity.

This wasn’t the first time Toyota had been involved in this kind of operation in the city. According to the New York Times:

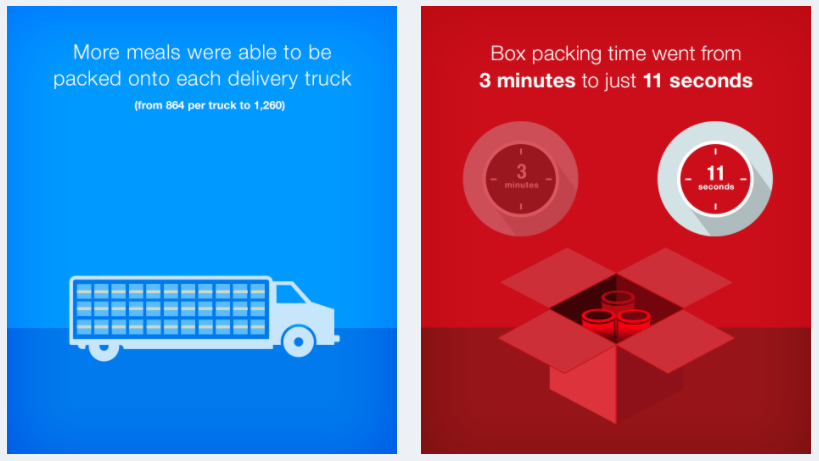

At a soup kitchen in Harlem, Toyota’s engineers cut down the wait time for dinner to 18 minutes from as long as 90. At a food pantry on Staten Island, they reduced the time people spent filling their bags to 6 minutes from 11. And at a warehouse in Bushwick, Brooklyn, where volunteers were packing boxes of supplies for victims of Hurricane Sandy, a dose of kaizen cut the time it took to pack one box to 11 seconds from 3 minutes.

It’s this last example which we’ll explore.

When the team entered the food bank, their primary job like always was to understand how the organization currently operates. One way they utilized this embedded analysis within their critique was to map it out visually. They drew a sketch of the current operating system – where food was located, where boxes were located, where people had to walk – and tried to understand the current routes which were being taken.

Their small visual chart demonstrated that lots of time was being wasted going from box to food and back again; uncertain what to grab and uncertain where to put it.

Their goal was to find a new way to structure this flow.

What they created was akin to a factory production line where each person took up a specialized role: one person on tins, one person on bread, etc. Other people would have the dedicated job of moving new boxes of produce into position to be deployed on the line. Others would take the role of transporting packed boxes onto their pallets for distribution.

This specialization meant that each person knew what they were responsible for and improved their ability to do it successfully and efficiently.

But creating the production line also needed an analysis of the available materials. Toyota made two key changes:

- They brought in rollers so that boxes could move down a central production line while workers stood still. This ramped up efficiency by adding pure speed to the process.

- They weighed up the size of the boxes with the amount of produce intended to be given in each parcel. They found that the boxes were bigger than they needed to be. On discovering this, they ordered new boxes which held the intended amount almost perfectly, meaning that more boxes could be added to each pallet for distribution.

To cut the packing time down from 3 minutes to 11 seconds is phenomenal. Equally, the number of parcels per truck was able to increase from 864 to 1260.

But the real success of the project was that they were able to serve 400 more families in half the time.

But the real success of the project was that they were able to serve 400 more families in half the time.

Eye Center Clinic cycle time was reduced 50%

As with all large organizations, dealing with the sheer volume of customers or users can prove a challenge.

It is also clear that an immediate way to improve performance is to be able to serve more of those users in less time.

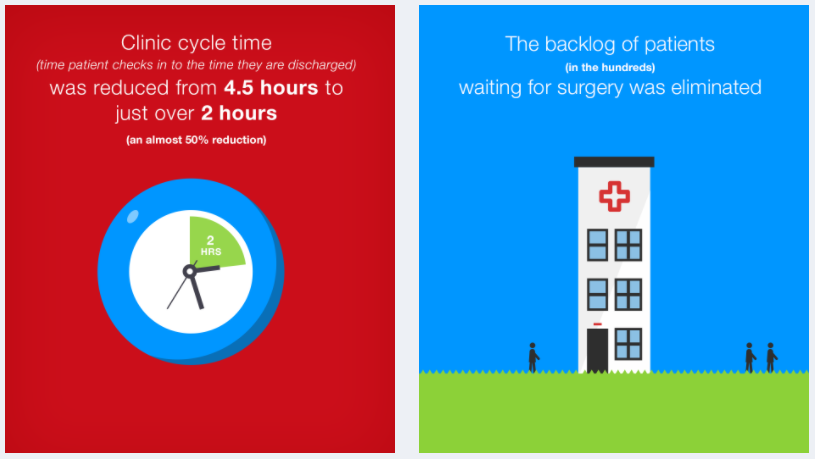

In short, this was the problem facing Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, in particular their Eye Center Clinic. They wanted to make sure they were operating as effectively and efficiently as possible. When they worked with Toyota, patient care and the ability to serve more patients was of utmost importance.

In order to deal with this, Toyota took on a patient centric approach.

One of the key concepts they focused on while attempting to understand and reconstruct the patient’s journey was the idea of waste – muda in Japanese. It was important to understand how waste operates within this context and then what could be done to reduce it.

It was concluded that the only moments in the process which contained significant added value were consultations; time the patient spends talking with, being examined by, or operated on by a medical professional. Patient interaction with medical professionals was seen to be the time where value could be created, which meant that inversely, from a patient’s perspective and an operational perspective, time not in consultation was waste.

Therefore, the Toyota team, now they had conceptualized waste for the parameters of this exercise, could focus on reducing that waste.

The focus was on the administrative processes and streamlining how patients were handled in waste periods. Some steps were as simple as color coding files and reorganizing equipment.

The focus was on the administrative processes and streamlining how patients were handled in waste periods. Some steps were as simple as color coding files and reorganizing equipment.

The end result was that the backlog of patients was wholly eliminated by reducing cycle time from 4.5 hours to just over 2 hours.

Let Process Street help your continual improvement

These approaches advocated by Toyota:

These approaches advocated by Toyota:

- genchi genbutu – to “go and see”, to embed yourself in the system and observe,

- kaizen – to employ ideas of continual improvement, making small iterative changes,

- muda – to identify waste, and to recognize that what constitutes waste is contingent on your situation,

… are not unique to their operations or limited to certain applications.

These principles and approaches have been taken from car manufacturing and redeployed to build houses, feed hungry families, and save lives. And you can use them in your own business too!

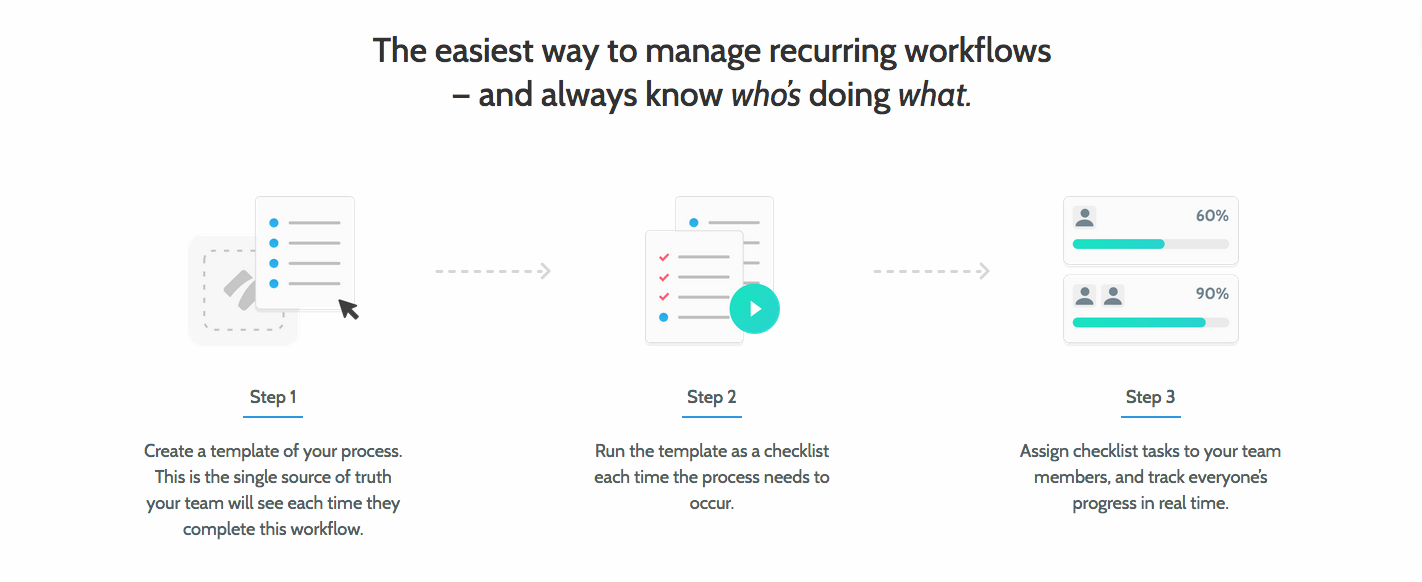

Process analysis, improvement, and implementation is what Process Street is all about. We’ve crafted our template structures to allow them to be collaborative spaces where you can understand progress and performance. We aim to see those processes tinkered with and adapted as users iterate and optimize.

Learn the lessons of Toyota. Use Process Street to document and improve your processes to make a success of whatever you need to do.

What are your feel-good process implementation stories? Have you experienced these improvements first hand? Let us know in the comments below!

Adam Henshall

I manage the content for Process Street and dabble in other projects inc language exchange app Idyoma on the side. Living in Sevilla in the south of Spain, my current hobby is learning Spanish! @adam_h_h on Twitter. Subscribe to my email newsletter here on Substack: Trust The Process. Or come join the conversation on Reddit at r/ProcessManagement.