Teams are like families.

Teams are like families.

No, I don’t mean in that cheesy, woo-woo “We are family” way we all roll our eyes at.

Yeah. I’m gonna be singing that song all day.

Teams are like families in the very literal sense that you’re thrown together with a bunch of random people you may or may not have anything in common with, may or may not even like, forced to interact on a daily basis, and expected to – somehow – make that all work.

If you’re lucky, you end up with the Bradys; less lucky, you’d be right at home among the Bluths. Or the Bateses.

Most of us – hopefully – probably end up somewhere in between, but team psychological safety is important even if your manager isn’t hiding in the attic after faking his own death. The fact is, though, you can’t force psychological safety; it has to be something you create organically – as a team. Not everyone’s sense of safety will be the same, and more significantly, each person may not be able to explain exactly why or why not they feel safe in a particular group or situation.

The fact is, though, you can’t force psychological safety; it has to be something you create organically – as a team. Not everyone’s sense of safety will be the same, and more significantly, each person may not be able to explain exactly why or why not they feel safe in a particular group or situation.

But fear not, dear reader: I have a solution. By focusing on your team’s workflows, you can substantially improve their psychological safety and foster an environment of mutual trust and respect.

Coincidentally, perfecting workflows is what we do here at Process Street, so in this post, I’ll explain five ways you can use workflows to improve psychological safety within a hybrid team.

- What is psychological safety?

- The impact of psychological safety on team performance

- How to improve your team’s psychological safety

- Your 2-minute psychological safety check

What is psychological safety?

![]()

“Team psychological safety is defined as a shared belief that the team is safe for interpersonal risk-taking.”

– Dr. Amy Edmondson, Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams

Edmondson goes on to explain that this is a tacit belief – people don’t talk about it, in other words. It’s one of those things that we only really notice when it isn’t there. Very rarely are we hyper-aware of situations where we feel safe or comfortable. On the other hand, if we’re uncomfortable or at risk, that’s pretty much all we can think about.

For the same reason, psychological danger can absolutely destroy a team’s productivity. If you look at the diagram below, you can clearly see the effect psychological danger and psychological safety have on each other:

The focal point of psychological danger is fear; fear of failure, fear of blame, fear of judgment. On the most extreme side, you have a team of automatons who are just going through the motions. Loyalty, innovation, well-being, and productivity are essentially out the window if your team perceives their environment as dangerous.

The ultimate endgame? You lose your team – and their talents – to another organization. Probably one of your competitors.

In a psychologically safe environment, individuals allow themselves to be vulnerable around each other. This doesn’t mean that your team is sharing all their most intimate thoughts and feelings, but they are willing to share their creativity.

Sharing an idea can make a person feel even more fear and exposure than sharing an emotion. We all worry about appearing unintelligent or inept. We all want to be respected for our skills and abilities. We’re all trying to prove we know what we’re doing – to our peers, but also to ourselves.

When we feel psychologically safe, we no longer have that fear of judgment. If we make a mistake, we make a mistake. It happens to everyone at some point. That makes us more willing to communicate openly with our peers, take accountability for our work (even if it’s not perfect), and to play an active role in the team.

Note: Psychological safety is not the same as trust. While they are similar, trust is a personal experience (will I trust Oliver to edit my work?); psychological safety is about the group (will the team shun me for writing posts the length of tiny novels?).

The impact of psychological safety on team performance

So I mentioned that sharing ideas and creativity can be difficult. Anyone who’s made something – a cake, clothing, a painting, a program – understands the anxiety that comes with finishing a project and knowing that someone else is going to see and assess your efforts.

Let me tell you a story.

I did my undergraduate degree in creative writing. Maybe not the most practical degree, but hey – I got a job writing so (especially to that one immigration agent who burst out laughing when I told her my major).

In my final year, we were split up into groups of about 5 or so for dissertation supervision. Peer feedback was something we’d done throughout our degree; it’s a staple of all creative writing courses and can either be awesome and stimulating or worse than having needles shoved under your fingernails.

For each seminar, we read a section of our classmates’ dissertations, and then we’d discuss them as a group, offering feedback and so on about how it could be improved, advice on obstacles that person was facing, etc. We had a great supervisor – okay, I was her favorite, but still – and for the most part, the group worked really well.

But there was this one guy.

He would not take any feedback whatsoever – not even from our supervisor. If any of us suggested even phrasing a sentence slightly differently, he’d argue against it with a level of passion most people reserve for human rights or climate change.

Fair enough. No one is obligated to take on feedback or critique. That would have been fine – if he didn’t also tear down everyone else’s work – even contradicting our supervisor.

Ultimately, the rest of us shut down. We stopped giving him feedback – obviously – but we also stopped giving each other feedback. The seminars turned into very long, painful sessions of silence with our poor supervisor trying her best to wrangle the unwrangleable.

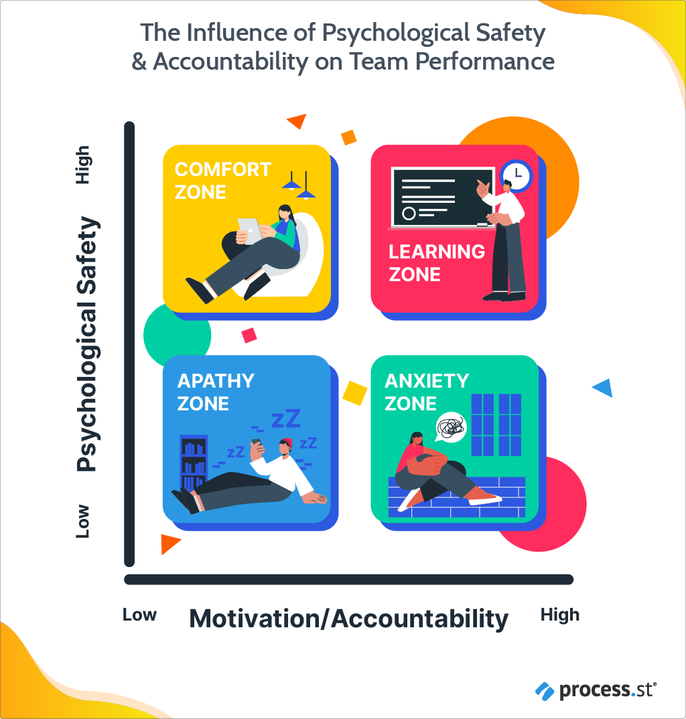

According to Dr. Amy Edmondson’s diagram of the four zones of psychological safety, we can place that seminar group pretty squarely in the “apathy zone.” Motivation (ours) and accountability (his) were both incredibly low, and, as a result, our feeling of psychological safety suffered.

The apathy zone is the least productive zone your team can be in. This would be the zone for those automatons I mentioned earlier. It is not a good zone for your team to be in at all.

High psychological safety and low motivation create the “comfort zone.” Your team may be happy, but there won’t be much innovation and change because they want to maintain the status quo. Who wouldn’t? The comfort zone is awesome, but also not very productive.

The opposite – low psychological safety and high motivation – creates anxiety. You’ll have a team that’s highly motivated to do better, but also fearful of repercussions if they fail. A team in the anxiety zone will generally get things done, but they won’t appreciate their accomplishments.

The sweet spot is the learning zone. This zone has both high psychological safety and motivation, which creates a team that is healthy, productive, and innovative. The focus here is on learning from any mistakes rather than reprimands or punishment, which allows team members to take reasonable risks and exert some control over their environment.

How to improve your team’s psychological safety

Let’s be honest – the last time someone pulled you aside and emphasized exactly how safe and trustworthy they are, you got a little creeped out, didn’t you?

The most misapplied phrase in writing advice is “show, don’t tell.” When it comes to your team’s psychological safety, though, it actually works really well. Your team won’t feel safe just because you decide they should be, think they should be, or even tell them they should be. You have to show them.

There isn’t a quick fix – especially in a hybrid work environment – but the following tips will get you started on the right path. As long as you stick with these practices and keep checking in with your team, you can feel confident that you’re providing the best environment possible for them to work in.

Tip 1: Document your processes

I cannot stress the importance of simply writing things down. Regardless of where your team is working – in the office, in the wild, both – proper process documentation is the only way to keep everyone on the same page.

When you take people out of the office – or have different people in the office at different times – documentation becomes that much more crucial. There may not always be a manager or team leader available to answer questions or provide specific direction. If all of your procedures and processes are documented, though, it won’t matter how experienced or junior an employee is: everyone on the team will have access to the same information.

Tip 2: Encourage critical thinking

The entire team should be involved in thinking about how the processes work as they use them. Is there a task that frequently gets skipped over? Is a set of directions unclear or confusing? Is there a task that should be included but isn’t?

This keeps your workflows accurate and up to date – which is great – but it also provides your team with a sense of agency and ownership. Rather than having tasks dictated to them, they are given an active role in the development and maintenance of the workflows they use the most.

Agency, ownership, and involvement definitely improve morale, but they also increase employee contributions. They know they have a voice within the organization, and so are much more likely to speak up about an issue.

Tip 3: Integrate communication channels

Working remotely has a lot of perks – very casual dress code, plenty of free snacks, no need to make small talk when you just want a cup of coffee – but it can also be pretty lonely and isolating. Remote companies tend to be pretty quick about establishing good communication channels for this very reason. When there’s no central office for anyone to gather it, that’s a no-brainer.

For hybrid workplaces, it’s not so obvious. It can be easy to fall into old patterns of traditional in-office communication procedures which inadvertently leave out your remote employees, or cause gaps in communication.

It’s a morale issue, too. In-person relationships develop naturally and organically; remote relationships need to be deliberate and intentional. Your remote employees need to be able to connect with their colleagues just as much as your on-location employees so they can build those connections.

Tip 4: Structure roles & responsibilities around the workflow

![]()

“Good design is obvious. Great design is invisible.” – Joe Sparano, Graphic designer

This bit of advice actually came from one of our product designers, but it applies to internal workflows as much as customer-facing interfaces.

Basically, he said, think of a car. We all expect a pretty standard layout of where the steering wheel will be, and so on. Different models will have extra features arranged a little differently, but the main elements are so easy to find you don’t even have to think about them.

![]()

“Good workflows are obvious. Great workflows are invisible.” – Leks Drakos, insightful content writer

Just like a car, any person filling a role should be able to step into your workflow and intuitively drive it with little or no difficulty.

I use a blog post production workflow for every post I write. It details every single step from the initial outline to actual publication. Imagine there’s a zombie apocalypse in my city and I don’t actually finish writing this post. Any of the other writers could take over and complete the process because everything they need to know – from resources to individual tasks – is built into that workflow.

In fact, even if the entire content creation team was eaten by zombies, anyone else in the company could still write and publish blog posts by following the workflow.

Tip 5: Separate the work from the person

Easier said than done, right? It’s difficult for both the person giving and the one receiving the feedback to not feel like it’s personal. Sometimes, though, you really do have to vehemently argue a grammatical point with a colleague that you otherwise get on really well with personally.

Feedback doesn’t have to be a negative experience, though – even if the feedback itself is a criticism. (I’ll dive into that more in a minute.)

People are much more receptive to feedback that is framed as a learning experience. It provides the individual with the feeling that they have the team’s support, and that their personal development is important.

Here’s an example:

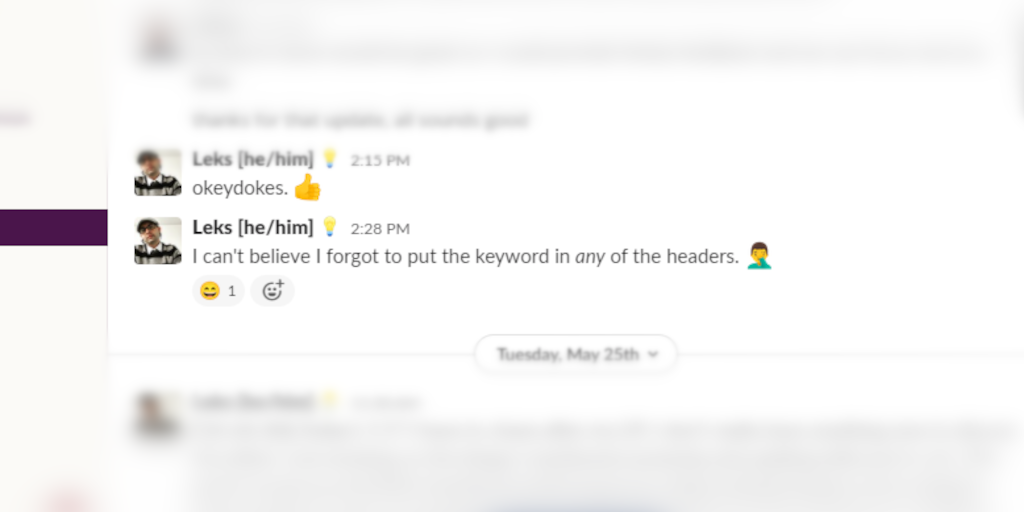

Critiquing the person: You didn’t put the keyword in any of the subheadings.

Critiquing the work: Some of the subheadings should include the primary keyword or a longtail keyword for SEO optimization.

It’s a subtle difference, I know, but it does have an impact. Think of it this way: Instead of telling someone they’re wrong, you’re showing them how they can perform better.

Your 2-minute psychological safety check

I have another story about peer reviews so gather ‘round.

Like I said – we have a blog post workflow we use every time we write something for Process Street. Part of that workflow is the peer-review process.

Peer reviews can be torturous experiences if done wrong. Some people – like my former classmate – get really hostile about any sort of criticism. Some are really, really blunt about the feedback they give. Critique – both the giving and receiving – is an art that takes practice. You have to learn how to give it and how to receive it.

So the example I just made about subheadings and keywords – true story.

A while back, I was working on multiple projects related to mergers and acquisitions. M&A everything is very complicated and, to be honest, I still don’t really understand a lot of it. Not the point.

I’d just finished one of the posts and fired it over to my colleague for peer review. At least once a week, someone on the team is reviewing my work and I’m reviewing someone else’s about as often. It’s part of our process.

It’s also all done in a public peer review channel. That’s right. Everyone gets to see which mistakes you made. Sometimes, we even do this live, during a meeting, where everyone on the team gets to give their opinion on what you’ve done.

It sounds like a recipe for disaster, but it’s not. Because this process is built into our workflow, because it’s done with full transparency, because it’s also pretty egalitarian (everyone gives feedback to everyone, regardless of seniority or position) – peer reviews are just part of the everyday work that needs to be done.

So when my colleague points out that some of the subheadings in my post could be better optimized vis-à-vis keyword placement, my response isn’t: “Oh no, I screwed up and I’m going to get chewed out about it.”

It’s: On our team, we all know that it’s okay to make mistakes. I mean, we’d prefer not to, naturally, but if we do, it can be fixed. Not only that, but our team members will catch those mistakes before they go public and have the chance to be really embarrassing.

On our team, we all know that it’s okay to make mistakes. I mean, we’d prefer not to, naturally, but if we do, it can be fixed. Not only that, but our team members will catch those mistakes before they go public and have the chance to be really embarrassing.

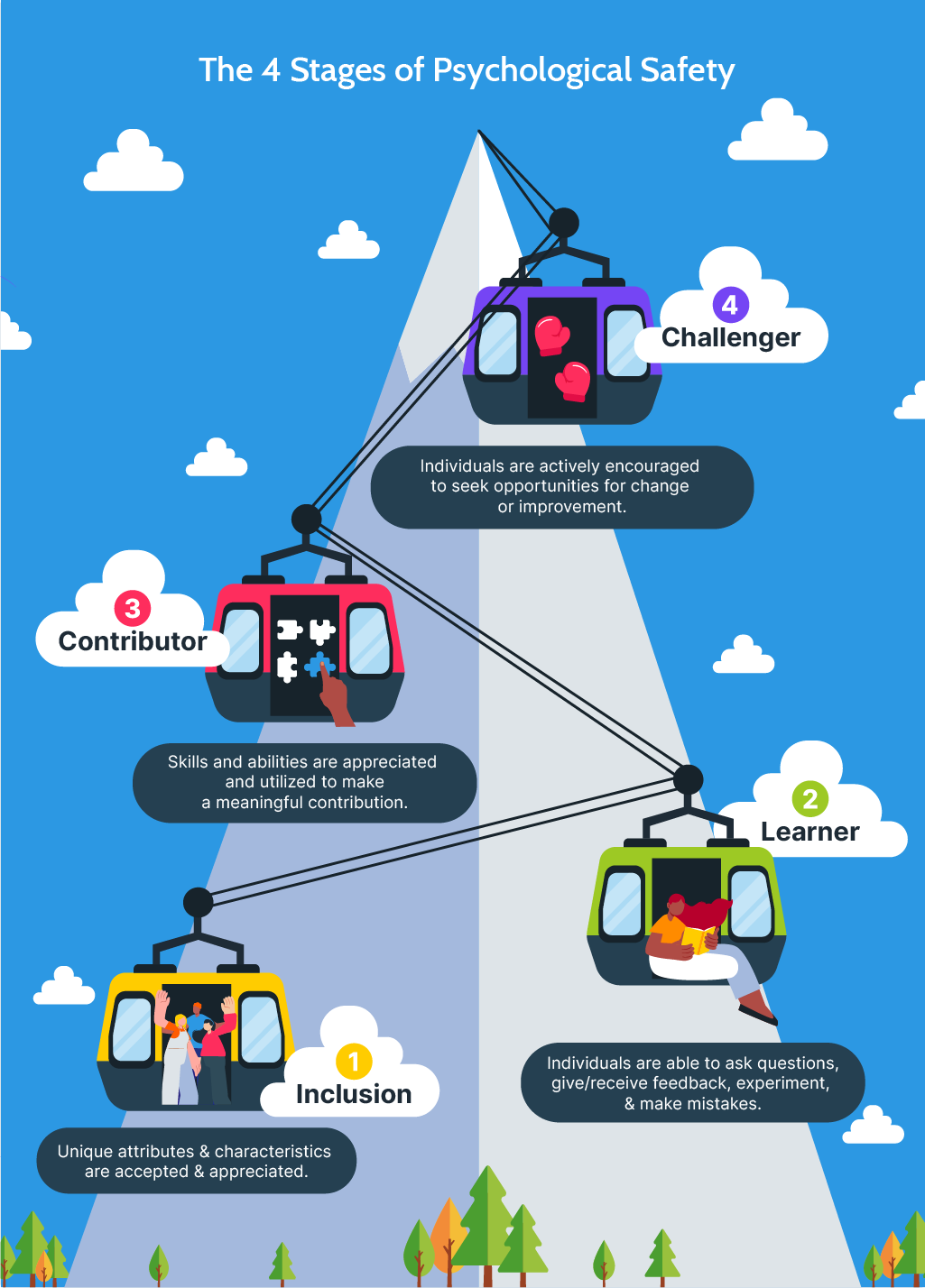

The 4 stages of psychological safety

Dr. Edmondson has also outlined the four stages of psychological safety that individuals can move through. Like most linear models, it shouldn’t actually be viewed in a linear fashion, but people like lists so here we are.

Dr. Edmondson has also outlined the four stages of psychological safety that individuals can move through. Like most linear models, it shouldn’t actually be viewed in a linear fashion, but people like lists so here we are.

People don’t necessarily move through these steps in this order – or even in any order. It’s completely possible that one person goes through all the stages at once while another takes several months to do the same thing. Someone else may go through the Contributor stage, then the Inclusion stage, then the Challenger stage, but at that point stop feeling like their skills are appreciated and so need to reach the Contributor stage again.

As a result, I consider these to be more akin to elements or attributes of psychological safety rather than separate and specific stages:

- Inclusion: Unique attributes & characteristics are accepted & appreciated.

- Learner: Individuals are able to ask questions, give/receive feedback, experiment, & make mistakes.

- Contributor: Skills and abilities are appreciated and utilized to make a meaningful contribution.

- Challenger: Individuals are actively encouraged to seek opportunities for change or improvement.

Your 60-second psychological safety check

Assessing the psychological safety of your team and/or workplace is pretty easy. It will literally take you less than a minute.

Answer yes or no to each of the following statements:

- I’m afraid of my colleagues’ reactions if I make a mistake.

- My colleagues are often dismissive when I try to bring up tough issues.

- My colleagues have been known to reject others for being different.

- I’m not encouraged to try new things at work.

- I don’t feel comfortable asking my colleagues for help.

- My colleagues have been known to sabotage each other’s work or reputation.

- I frequently get assigned tasks that don’t fully utilize my skills and abilities.

In an ideal work environment, your answer should be “no” to each of them. If you answer “yes” to all of these, it’s time to take an in-depth look at how your team operates. Most likely, though, there will be some yeses and some nos.

Think about the statements that were answered with a yes, and consider how they can be corrected. Discuss the options with your team and really listen to what they have to say. Asking for – and acting on – your team’s input is the first step in improving the overall psychological safety of the entire team.

How do you foster psychological safety with your team? Let us know in the comments below!

Leks Drakos

Leks Drakos, Ph.D. is a rogue academic with a PhD from the University of Kent (Paris and Canterbury). Research interests include HR, DEIA, contemporary culture, post-apocalyptica, and monster studies. Twitter: @leksikality [he/him]