The following is a guest post from graphic designer and copywriter Erik Fessler.

What do you think is worse: sitting for 100 days because you didn’t know what direction to travel in, or going for 100 days down the wrong path?

Here’s the good news:

This question doesn’t matter if you have a reliable and logical process to find the right direction.

Brainstorming is the key to finding that direction, and it’s something you can implement for your team in a logical, structured way. With that in place, you can use that process as a reliable way to generate ideas, iterate upon them, and harness the power of your team’s combined creative energy to make real business change. That is, if you can build and optimize your brainstorming process…

Alex Osborn was the first person to write about brainstorming in his book Applied Imagination.

The author of Applied Imagination, a Madison Avenue advertising executive, was frustrated by his employees’ inability to develop creative ideas for ad campaigns.

He began hosting group-thinking sessions in 1939 and noticed an improvement in the quality and quantity of the ideas produced by his employees. He continued to develop the technique, formally outlining the practice in his 1953 book on organized creativity.

Brainstorming is the best roadmap for making the decisions that count. It steers us away from indecision while reducing the likelihood that we go too far down the wrong path.

Brainstorming is a critical decision-making process, yet it works best when approached with a purposeful and lighthearted attitude. Using lateral thinking, it solves problems by taking an indirect and creative approach. Brainstorming is meant to help us view a problem in a new and unusual light.

The basics of a brainstorming process

The brainstorming process relies on two important keys: rapid idea generation and non-threatening communication.

Brainstorming keeps us moving and helps us avoid dead end paths. It forces us to consider all of our options. It’s tempting to adopt the first solution we think of while trying to make an tough decision. Unfortunately, the first solution isn’t always the best. Consider this excerpt from Art & Fear: Observations On the Perils (and Rewards) of Artmaking by David Bayles and Ted Orland:

“The ceramics teacher announced on opening day that he was dividing the class into two groups. All those on the left side of the studio, he said, would be graded solely on the quantity of work they produced, all those on the right solely on its quality.

His procedure was simple: on the final day of class he would bring in his bathroom scales and weigh the work of the “quantity” group: fifty pound of pots rated an “A”, forty pounds a “B”, and so on. Those being graded on “quality”, however, needed to produce only one pot – albeit a perfect one – to get an “A”.

Well, came grading time and a curious fact emerged: the works of highest quality were all produced by the group being graded for quantity. It seems that while the “quantity” group was busily churning out piles of work – and learning from their mistakes – the “quality” group had sat theorizing about perfection, and in the end had little more to show for their efforts than grandiose theories and a pile of dead clay.”

Students who didn’t explore multiple ideas traveled an entire semester down the wrong path. It’s tempting to wish for a quick “eureka” moment.

Ralph Keeney, former professor at Duke University and consultant to large organizations such as the Department of Energy, suggests pushing harder. He instructed readers to produce five alternative ideas for every initial solution they dreamed up in an interview with Forbes. This 5:1 ratio may seem intimidating, but it is achievable when paired with the second key to brainstorming, comfort.

Rapid idea generation is most achievable in no-loss situations. Creativity flourishes in focused yet low-pressure environments. This doesn’t excuse creatives from meeting their deadlines. But it does require that those who participate in brainstorming sessions avoid criticizing or overly rewarding other’s ideas.

All ideas generated by brainstorming should be judged and the valuable ideas should be flushed out, however this occurs in a later stage of the process. This is why non-threatening communication is the second key. Now that we’ve covered the basics of brainstorming, we’ll cover a three step process applying it to making business decisions. This process will talk you through facilitating a brainstorming session at your organization.

Step 1: Brainstorm the right questions

The first step to finding the best answers is asking the right questions. Using brainstorming to lay out unknown factors is as important as working together to find the answers. The questions you produce will guide you towards the right paths, and help you avoid the wrong ones.

Brainstorming the best questions is quick:

To start, prepare a two minute pitch that covers all the problems or sets of problems your group needs to overcome.

It’s important that you, the group facilitator, respect this two minute rule. Being forced to quickly share the challenges your group is facing forces you to work in high-level frames that doesn’t constrain or direct questioning.

Remember, you’re highlighting the problems, not coloring them. It’s also good to describe how things would change for the better if the problem were solved. Think of yourself as a director, and your teammates are the actors who need to know what their motivation is.

As you begin your first brainstorming session, it’s important to set two rules.

- Participants may only contribute questions, and may not contribute answers to questions.

- Participants may not make preambles or justification for their questions.

It’s also important to get a basic inventory of the group’s emotional state before questions begin. Your goal is to figure out if the group feels positive, negative, or neutral about the session. This should only take a few seconds. You’ll do the same inventory when the session is over.

The group’s mood is important because emotional state effects creative energy. Quality brainstorming has a tendency to spark emotional boosts in groups, you should expect to see a booth in group moral if the session was successful. This emotional boost is also important because it makes participates more likely to follow up on their questions.

It’s time to start recording questions once the mood inventories are complete.

Shoot for a minimum of 15 questions in four minutes. Encourage shocking and challenging questions, but do not allow pushback on anyone’s contributions. It’s best to handwrite or type these questions on paper or take notes digitally. Whiteboards tend to take too long to write on to record input accurately.

Once the four minute timer has gone off, it’s time to do a second emotional inventory. How do you and the group feel now about issue you’re facing? If the answer is still resoundingly neutral or negative, you should consider re-running the exercise. Rerun the experiment at a later date if the group seems fatigued. Or switch in substitute members. Research suggests that positive emotional states help create creative solutions to problems. Groups also have positive moods if they no longer feel stuck, so repeat this group process until you have had at least one mood-positive session of questions.

Once you’ve finished collecting questions, it’s time to analyze your findings.

Look for questions that re-frame the problem, and may hint at a new way of solving it. The best questions should seem important or meaningful. If a question makes you feel uncomfortable, it’s worth looking into. Be sure to ask follow up questions such as “Why don’t we already do this?” Another great follow up question example is “Why don’t I feel comfortable delegating this responsibility to someone else?” Employees may find organizational and personal insights in follow up questions.

The second step in organization brainstorming forks into two separate methods. Both methods have their merits for solving different types of problems. If you are trying to solve a simple problems, or to focus on a broad issue, you should trying individual brainstorming. If your organization is trying to solve a complex problem however, be sure to read the section on group brainstorming.

Step 2a: Individual brainstorming

You may be surprising that individual brainstorming is the next step in your organization’s brainstorming process. Study after study however seem to suggest brainstorming works better if started individually. The studies indicate that the individual brainstorming results should be taken to a group meeting, and then discussed.

Experts credit this to the judgment free nature of individual brainstorming. Shy team members may fear mockery and rejection from teammates, despite how well the group in behaved. Individual brainstorming also minimizes distractions since the social aspect has been removed. This freedom from distractions is why individual brainstorming is optimal for the concentration-intensive nature of broad issues.

Once everyone involved in the brainstorming process has their individual ideas, it’s time to discuss your solutions. Have everyone present their findings, and then come to a consensus. The research shows that this type of group meeting is more likely to come to a correct answer on most types of issues.

Step 2b: Group Brainstorming

Group brainstorming is a winning tool for complex problem solving because it’s better at developing ideas in greater depth. It allows you to build a diverse team with different specialties and experience. Diversity is key to effective group brainstorming.

The group brainstorming facilitator should try to incorporate as much diversity as possible in their team, which should be five to seven members.

It’s worth noting the large number of studies that suggest diverse groups make better decisions, particularly when they are diverse racially, as well as among age and gender. McKinsey and Credit Suisse found in separate studies that diverse executive boards operate more profitably. Ethnically diverse groups of traders made better stock picks. Diverse courtroom juries deliberate longer, raise more facts about cases, and conduct broader deliberations than same-skin color juries. Diversity gives a group more personal experience data points to consider in it’s decisions.

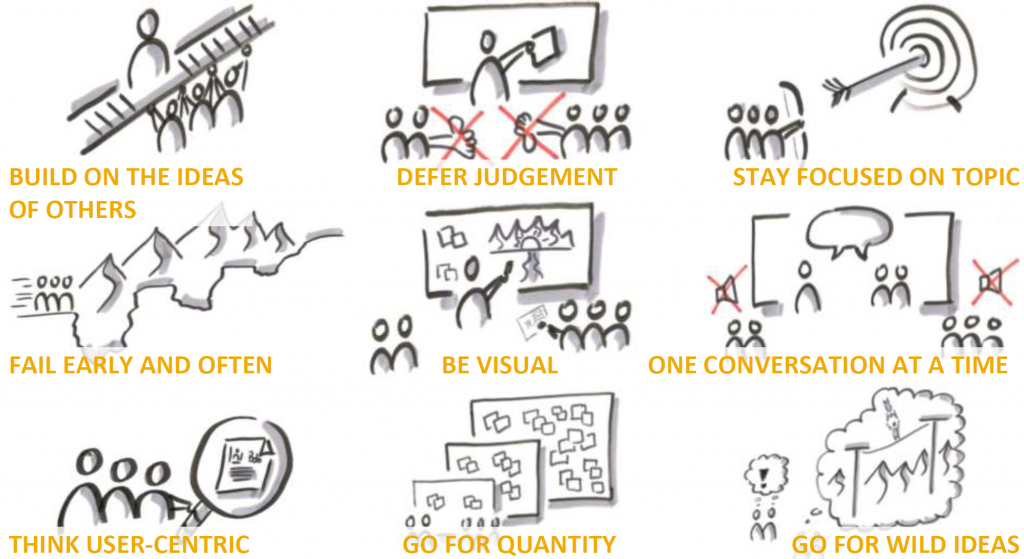

Diversity also helps prevent anyone from feeling like the odd one out, which keeps everyone comfortable. Comfortable people are more focused and under less pressure, which we already know boosts their creative thinking. As with our question groups, make sure no member dismisses another member’s suggestion no matter how unusual it may be.

Once the group is assembled, the facilitator must prepare their group. Make sure the group is walking into a comfortable meeting space, armed with a pen and paper.

Start the session off with a warm-up exercise or icebreaker if the group is unfamiliar to increase everyone’s comfort level.

Present the problem once the group is comfortable. Start by clearly defining the problem. Next, lay out any criteria that must be met. Be sure to incorporate any criteria you derived in the step one question phase. Have group members write down as many ideas as possible. Then have everyone share their ideas. Give everyone a chance to share, and make sure all ideas are recorded.

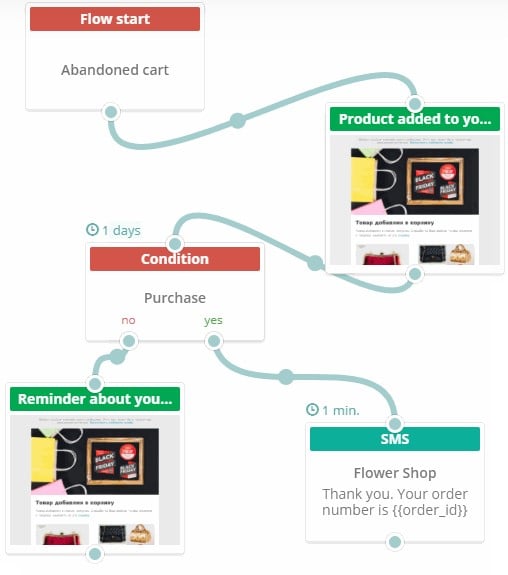

The facilitator or a dedicated scribe should record everyone’s ideas on paper or electronically. You can use Process Street form fields to record input as part of a larger brainstorming process.

Group scribes are cautioned to avoid whiteboards, as they slow brainstorming down by slowing down the writer. It’s also much easier to share the record with all group members after the meeting is complete.

Once all of the ideas have been shared, group members should build on each other’s ideas.

Everyone must develop someone else’s ideas, just as everyone should be expected to contribute new ideas.

It’s important for the sake of the ideas, but also for group moral. Team members feel more engaged with their work and with their group if they feel like they’re part of the solution. The group facilitator should contribute if they have anything to add, but most of their time and energy should be spent supporting the team and guiding the discussion.

The main goal of the facilitator is to ensure the group is having one conversation at a time. They also need to ensure the group isn’t getting sidetracked. But they shouldn’t necessarily get in the way of fun. The facilitator should welcome creativity and encourage ideas by any means necessary.

Use provocations and random input though experiments to get ideas flowing. But whatever you do, try to avoid following the same train of thought for too long.

Use breaks strategically to avoid this, especially if the brainstorming session is long.

Step 3: Don’t Forget to Take Action

Congratulations on building a strong list of incredible ideas! But it would be a shame if something were to…not happen with it.

It’s up to you as the group facilitator to ensure that the best ideas are sorted out, analyzed, and pushed forward.

Choose your favorite suggestion, develop a plan to enact it, and rope in the right team members to bring the idea to life.

If you’re stuck between two great ideas, consider A/B testing your top contenders.

Just remember, iteration is key. Theorizing is seldom ever a good replacement for learning by action. Don’t let your group’s brainstorming process become a pile of dead clay.

Workflows

Workflows Projects

Projects Data Sets

Data Sets Forms

Forms Pages

Pages Automations

Automations Analytics

Analytics Apps

Apps Integrations

Integrations

Property management

Property management

Human resources

Human resources

Customer management

Customer management

Information technology

Information technology

Benjamin Brandall

Benjamin Brandall is a content marketer at Process Street.