Have you ever had a project which never seems to end? One which you either underestimated or kept adding tasks to as you went along?

That’s exactly what setting out your project scope will prevent.

By analyzing the elements of your projects before starting, you can set out the scope of the work in order to prevent extra work getting added (without adjusting the necessary resources) and avoid taking on projects too large for your team to handle.

Not to mention that the principles behind project scope can be applied elsewhere in your business too.

“I call this the Scopi-locks principle.

Don’t make your product too big, because no-one will adopt it. Don’t make your product too small, because it’s not worth adopting. You have to [get it] just right such that it’s worth poor people pulling it into their lives and, when they do, that they get some value out of it.” – Des Traynor (co-founder of Intercom) on product scope

Let’s get stuck right in with project scope by breaking down what it is, what you need to know before creating it, and how to use it in action.

What is project scope?

“Project scope” is a term mostly used to describe everything that’s involved with a particular project, both in what it aims to achieve and how it will get there. Think of it as the boundaries of your project – everything within the scope is relevant, anything outside of the scope can and should be ignored to align with expectations.

In this way, calculating the scope of a project allows project managers to know how much work a particular goal should take, what timeline and budget can be expected, and even how to tackle common issues should they arise. This, in turn, solves potential issues such as evenly delegating work, making sure that everyone (employees, stakeholders, etc) knows what the project involves, setting realistic deadlines, sticking to budgets, and making ideal points for collaboration more obvious.

This is usually done by working out (and clearly documenting) precisely what the project is designed to achieve, how that goal will be reached, how progress will be tracked, and what resources (time, money, expertise, etc) will be required to do so.

Before diving into each of the elements of project scope, it’s worth noting that the principles behind why this idea is important can be applied across multiple disciplines. For example, scope is just as vital in providing the boundaries for a process you need to document, and in breaking up development sprints to ensure that everyone has the same (or similar) workload.

Not to mention that presenting the scope of a project (commonly in a dedicated “project scope statement”) is one of the easiest ways to highlight the value and cost of a project to upper management figures or stakeholders. Instead of needing to speak to your entire team, a single scope statement can explain the entire thing at a high enough level that the pros and cons can be easily understood.

So, project scope is vital to planning a successful operation. However, in order to define your scope, you’ll first need to break it up into smaller elements.

Project scope elements

To determine project scope, you need to know:

- Project objectives

- Deliverables

- Process (tasks/method)

- Timeline (or rough deadlines)

- Budget

Each of these elements is useful by itself, but together creates a comprehensive scope which shows you, your team, and any stakeholders exactly what the project involves, what it will do, and how much/long it will take to perform if all goes to plan.

Project objectives

Project objectives are exactly what you’d expect; they’re the goals that the project is intended to achieve. This could be anything from “improve support for employees who need it” to “address complaints with our client onboarding process”, and should be as clear and concise as possible (ideally spanning a single sentence).

One way to write a succinct project objective is to think about the intended effects of the project and relate them back to the project, team, or company as a whole.

Above all else, the objective needs to be agreed upon by everyone involved (including stakeholders), be realistic and avoid jargon. If possible, challenging the team by setting an objective that pushes their abilities is also a great way to get them engaged with the project.

Multiple objectives are common, but always be wary to keep the project realistic in what you can achieve in a reasonable amount of time. If the objectives span too wide, consider whether the project can be split up into smaller, more immediately beneficial endeavors.

Deliverables

Project deliverables are things which are (or need to be) created or affected by the project. These are often the elements which will be measured in order to track whether objectives are being met and, as a result, don’t have to be a physical item (often they are a statistic, document, or so on).

There’s not much else to say here – deliverables range from products to documents, reports, survey results, new web pages, and everything in-between. The key to identifying them is knowing what you intend to produce or affect according to the project objectives.

If in doubt, try thinking of all of the benefits you want to achieve with the project and the aspects, documents, and physical products which go into achieving that.

Process

The project’s process plays another vital role in showing the scope of the project, as this will demonstrate exactly what is involved in achieving the objectives and producing the deliverables you’ve already noted down. Think of this as the task list which your team will need to follow in order to carry out the project.

This doesn’t need to be anything fancy; a minimum viable process is more than enough to get the point across, so long as your task list is clear and understandable to all without leaving room for interpretation.

Having a documented process is beneficial to any future projects too, since the process will already be there to use to make your project’s success more reliable. Plus, if any problems pop up during the project they can be noted down and the process can be altered in order to avoid such problems next time.

As you can imagine, this is especially beneficial with projects and tasks which are commonly performed, such as a blog pre-publish checklist (as shown above) or your employee onboarding process.

Timeline

The timeline of the project is a key element to the scope, as this will indicate how long the team will have to complete their tasks and also how many employees will be required.

This is another point which should be discussed with stakeholders or upper management, as this will directly affect how large a return on investment they will receive. As such, while there should be a rough timeline detailing how long the basic elements will take to perform, it’s a good idea to include a couple of variations or side-notes to expand upon it and provide alternatives.

Let’s say that you have a project which will take a week and two employees full-time to complete the bare minimum work – this is the base timeline (which will be broken up into the relevant tasks).

However, it’s known that a few optional tasks can be performed in order to increase the value of the project. Therefore, an alternative timeline should also be provided to account for the extra work should the stakeholders want to invest the extra time and resources.

As a final note, it’s also worth providing a buffer zone if possible where problems are likely (or possible) to occur. This will help to make sure that the project stays either on track or slightly ahead of schedule even if something slows the team down.

If you haven’t already, check out our collection of free timeline templates!

Budget

A project’s budget contains many of the same aspects as its timeline. It’s calculated by breaking down the costs associated with performing the work set out in your task list, but if flexible based on the work involved and what stakeholders or upper management are willing to pay.

This is a key area of negotiation, and can easily affect other project elements such as the task list, timeline, and even objectives.

For example, if more funds are available than expected this might result in the timeline being shortened (due to having more resources) or extra work being added and the project gaining value overall.

Not everything can be planned for, and so the same approach should be taken as with the timeline. A basic budget should be calculated (including a breakdown of the price list), but attractive or predicted optional extras can also be priced up to give options to those involved.

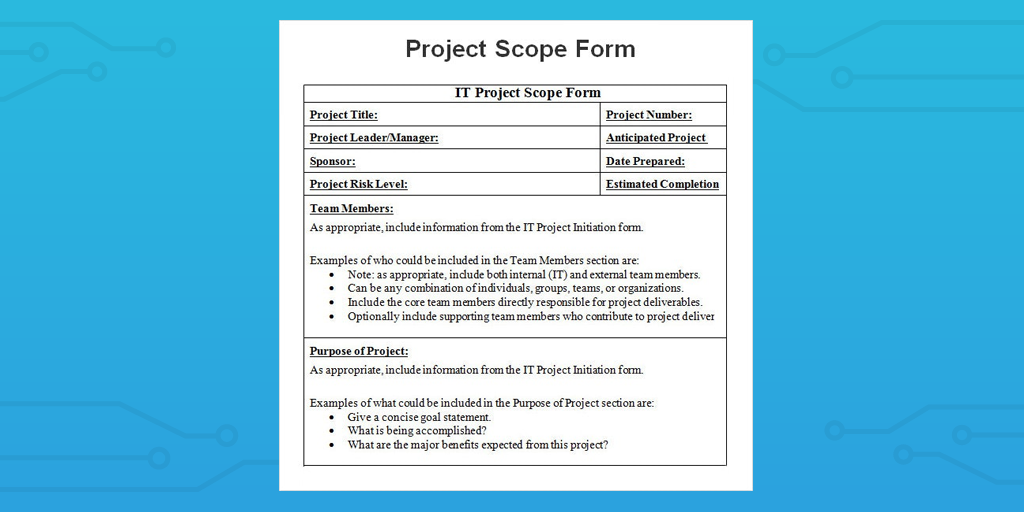

Project scope statement

Now that we’ve detailed all of the relevant aspects to the project scope, it’s possible to create a project scope statement. This is a summary of all of the elements above, albeit condensed into an easily digestible paragraph or so of text.

In other words, the scope statement should include the objectives, reference deliverables, note the timeline and budget, any significant milestones and, preferably, the process(es) or tasks involved. This should all be in language which everyone can understand (eg, no jargon or overly technical terms) so that the scope statement will be able to show stakeholders, management figures, and employees alike what the project is, what it will achieve, and where the limits of the project lie.

It’s worth noting that not all scope statements contain a strict timeline or budget (these can always be attached as supporting documents), but the overall objectives and milestones are always central.

Once the scope statement is written it can be presented to stakeholders or senior company figures for review. The result of this will be approval for the project to go forwards, rejection (ideally with a description of why the project won’t be carried out), or negotiation in order to alter the scope before the project starts.

After the project scope is agreed upon, this scope statement (along with the individual elements from earlier) will serve to keep the team on track and only performing relevant work. This is key to preventing scope creep.

Scope creep

We’ve all had a project which involves far more work than we first anticipated. Whether due to unforeseen complications, bad planning, or extra tasks being added to the pile mid-way through the project, this often leaves teams scrambling to stay on target and meet their deadlines.

At best, employees will be stressed and risk burning out due to extra (unexpected) work without increasing their resources. At worst, the project will be completed to a substandard level due to the rush, or even collapse entirely.

This is called scope creep, and it’s the number one reason why clearly defining your project scope is important to do before starting work.

Now, I’m not saying that expanding a project’s scope halfway through is always a bad thing. However, trying to do so without due consideration for how the rest of the project will be affected causes major problems.

This is why it’s good to provide several potential timelines and budgets, with optional extra tasks calculated ahead of time in order to provide a flexible scope which suits both the team carrying out the project and the needs of stakeholders.

Think of it like booking a flight. The primary objective would be to book a flight to your desired destination, but there are many optional extras which can add value to your purchase for an additional fee. It’s not necessary for you to book a first class ticket, pay for extra hold luggage, or to fly with a premium airline for the sake of comfort, but all of these are predictable options which you can take for a little extra money.

Process scope

In much the same vein as project scope, knowing the scope is vital when creating a process, and therefore in calculating the scope of projects which involve them. This helps by splitting up projects into assignable tasks and processes which can be reliably and consistently carried out, and by giving a set of instructions which makes sure that everyone knows what they should be doing at any given time.

The same principle applies here to project scope – you need to know what the process is designed to achieve and what it takes to achieve just that goal.

To that end, any processes built (at least, at first) should be nothing more than minimum viable processes (MVP). This means that the bare minimum is recorded in order to fulfill the objectives.

In other words, don’t worry about recording fancy instructions or making sure that your graphics fit a custom, consistent design. Heck, you don’t even need to have any text or details at all when recording an MVP – the only thing that’s needed should be the task list.

Once this is recorded you can then go back and fill in just enough specific detail in each task to make sure that everything is completed correctly.

To find out more, check out our other articles on the topic:

- How To Create a Process People Won’t Hate Using

- How to Build a Minimum Viable Process Pack for Your Startup

- Creating a Process Template

“Scope” includes knowing when you’re doing too much

Whether taking on a project or process, a large part of figuring out the relative scope is knowing when to draw the line at the responsibilities and tasks involved. Remember – the whole idea of creating a project scope statement is to present a digestible summary to stakeholders and upper management, so there’s no point in creating it if the project is too large to easily summarize.

Splitting projects and/or processes into smaller chunks is a great way to solve this issue.

For example, the blog pre-publish checklist and real estate sales process are both checklists we here at Process Street spent time researching and documenting so that our audience didn’t have to do the same. However, in both cases we found that scope creep was becoming a major issue.

The pre-publish checklist was too unwieldy and spanned both our content creation and promotional teams, covering everything from the initial idea and keyword research through to promoting the finished piece. Meanwhile, the real estate sales process proved a huge problem, as there was too many necessary steps to break down into a single functional checklist.

Both of these issues were solved by adjusting the scope of the processes and splitting them up into separate, smaller, focused checklists.

Our pre-publish checklist was split into our current process (with the objective of proofing a post to the point of publishing) and a separate content promotion process (which allowed for individually assigning tasks and tracking each post’s process). The sales process was simplified to retain a simplified task list, but link out to four other separate processes covering the pre-listing house cleaning, home staging, house viewing, and real estate listing tasks.

Scope is useful for more than projects and processes

Planning the scope of your efforts isn’t something that should be limited to just projects and processes; with a little creativity, the same principles can be applied across your entire business.

Take development, for example.

When planning a sprint, it’s useful to have a method for ensuring that the amount of work involved is consistent to make sure that your team isn’t overloaded in any particular period. This is usually done by giving tasks a number associated with the amount of work they take.

If a sprint is worth 20 points and there are four developers, that means that each employee can do five points worth of work in each cycle. This could be a single, large task worth five point, or several smaller tasks which add up to the same amount. In this way, the scope of the sprint is always the same and avoids piling too much work onto a single employee.

Ultimately, whether you’re using project scope, process scope, or another form of the principle, it’s a vital tool in any project managers arsenal. With careful application, you can prevent scope creep no matter what problems your team faces.

How do you handle project scope with your own team? I’d love to hear from you in the comments below!

Ben Mulholland

Ben Mulholland is an Editor at Process Street, and winds down with a casual article or two on Mulholland Writing. Find him on Twitter here.