How do you know whether you’re going to be successful or not with a new business or product?

How do you know whether you’re going to be successful or not with a new business or product?

Well, you’ll probably look to pour your heart and soul into it. You’ll work hard to make it the best product or service you can. You’ll endeavor to make each and every customer happy.

And well done to you for that.

But you’re not the only one who impacts on whether your efforts are successful.

It’s no secret that one of the hardest parts of business is the competitive nature of the market.

What your competition looks like, how it’s constructed, and what opportunities their weaknesses provide you, are crucial factors which can determine your success.

This is where you’ll need to do some kind of competitive position analysis.

In this Process Street article, we’ll look at a framework which is designed to help you understand your competition called Porter’s Five Forces. We’ll cover:

- What is Porter’s Five Forces Model?

- Porter’s Five Forces – Force 1: Threat of new entrants

- Porter’s Five Forces – Force 2: Threat of substitutes

- Porter’s Five Forces – Force 3: Bargaining power of customers

- Porter’s Five Forces – Force 4: Bargaining power of suppliers

- Porter’s Five Forces – Force 5: Competitive rivalry

- Resolving the 5 Forces: An Economic Moat

What is Porter’s Five Forces Model?

Porter’s Five Forces Model is a tool or a framework you can use to work out how competitive an industry is, and therefore how attractive that industry is for someone who wants to enter that industry and achieve high profits.

Highly competitive industries tend to result in lower profit margins as the competition leads to high levels of efficiency and tightening. If you want to see high profits – profitability – then you would benefit from either entering a less competitive industry or understanding an existing competitive industry well enough to be able to disrupt it.

This shows us that we can use Porter’s Five Forces Model in two key ways:

- As a yes/no tool. A way of checking whether a proposed venture or product would be worth starting or investing in.

- As an insights tool. A way of assessing an industry or market niche to find weaknesses or areas which could be exploited.

The model was originally proposed by Michael E. Porter in the March 1979 edition of Harvard Business Review in a paper titled How Competitive Forces Shape Strategy.

The underlying assumption is that strategy in business is essentially the art of dealing with competition. But Porter challenges this and asks us to be a little more nuanced:

[I]n the fight for market share, competition is not manifested only in the other players. Rather, competition in an industry is rooted in its underlying economics, and competitive forces exist that go well beyond the established combatants in a particular industry. Customers, suppliers, potential entrants, and substitute products are all competitors that may be more or less prominent or active depending on the industry.

Porter’s 5 Forces example: Idyoma: Local Language Exchange

I have a mobile app. It’s called Idyoma and it helps language learners connect with one another to meet and practice their languages. Having conversations in a language is the only real way to become fluent, so we try to help make that happen.

It functions a lot like Tinder, Bumble, or one of the other dating apps. You make a profile, it shows you other people with matching languages nearby, and then you can message them to meet. Pretty simple stuff.

We have a few competitor apps which are slightly different to us but have broadly the same premise. The traditional notion of strategy would be to see those competitor apps as our competition. Again, simple.

What Porter is asking us to do is to think of competition as being a much broader topic.

If someone searches for language exchange on the AppStore then our primary competition is those other apps. But there are lots of people who don’t search for an app when they want a social experience – they search on Facebook or Reddit; places they know already have social communities.

If you search on Facebook, you’ll find that almost all major cities have one or more dedicated language exchange groups. That is competition too.

Equally, if you were an investor looking at Idyoma, you would think about other kinds of competitors. What about well-funded monoliths like Duolingo? If they wanted to move into your space, how hard would it be for them to do so?

As we’re a mobile app, we don’t have to worry about things like suppliers jacking up their prices. But the low barriers to entry into the market could mean that we have to worry about new options cropping up regularly. Or, that there might be so many options for consumers that they don’t feel a strong enough need for any one product that they would be willing to pay a price high enough for us to be profitable.

While we worry about direct jostling with close competitors, an investor might be looking at the raw economics of the market and formulating different questions.

There is so much more to competition than just the other companies which offer the product you do.

That’s the fundamentals of what we can learn from Porter’s Five Forces. Let’s take a closer look into each to understand how you could apply them to your company or situation while relating back to our source material.

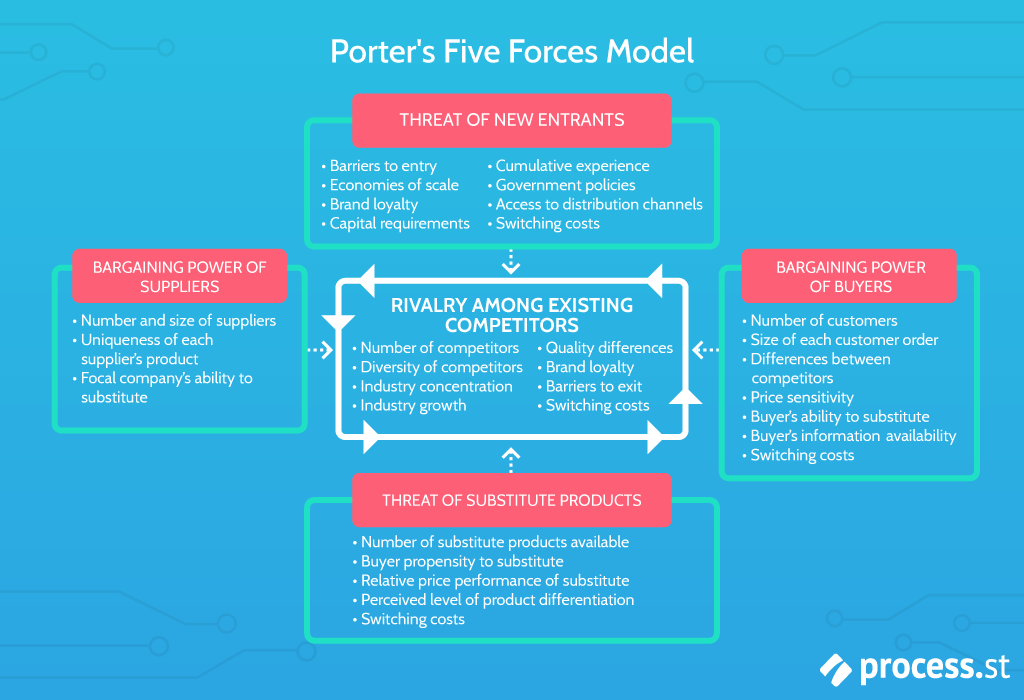

Porter’s Five Forces – Force 1: Threat of new entrants

New entrants to an industry bring new capacity, the desire to gain market share, and often substantial resources. Companies diversifying through acquisition into the industry from other markets often leverage their resources to cause a shake-up…

The key question here is whether another company could very easily offer the same product and enter the market.

The things which stop new companies entering a market are referred to as barriers to entry.

The six sources of barriers to entry

- Economies of scale – In many manufacturing industries products can only be offered cheaply because the cost of production per unit decreases as you produce larger volumes. Producing large volumes of a product requires refined knowledge of the materials you need, tightly honed production processes, and large investment in infrastructure and staff to deliver. This makes the initial investment needed very high.

- Product differentiation – In a mature industry, there will be a wide array of variants available already around core products. Entering a market like this can be tough as it is often difficult to find sufficient differentiation from the current selection. It may require an oversized marketing budget to break through customer loyalty.

- Capital requirements – Some industries simply require a huge amount of money to get started. This increases the risk from the beginning. The risk is even higher if a high proportion of this capital is put into unrecoverable expenditure like advertising, as opposed to investing in assets such as land or machinery.

- Cost disadvantages independent of size – There are often other costs to consider which can be very difficult to get around. An example of this might be patents and proprietary technology. Microsoft hold so many patents that it would always be difficult for another company to try to offer the same products as them. You would need to, as Apple have done, approach the space differently from a strategic perspective.

- Access to distribution channels – Distribution channels have changed dramatically since Porter wrote his original paper, but the fundamentals are the same. If competitors have exclusive agreements with the key buying locations of your consumers, then you’ll find it very difficult to reach your consumers.

- Government policy – In certain industries, it may be necessary to tender for government contracts, or to spend highly on a whole department of people who can ensure regulatory alignment – knowledge and a position on the experience curve which competitors already have.

There are also a series of other considerations surrounding how existing competitors would react if you tried to enter their industries. Uber has seen many of its drivers and cars attacked in cities it has tried to enter; so this threat can come from the ground. Or, it may be that your competitor has a lot of capital so they would be willing to artificially lower their prices for long enough to delay your entry and increase your burn rate.

How your competitor reacts isn’t one of the big 6 as it isn’t an economic structural critique, but one of agency.

Porter also leaves us with two points relating to the changing of barriers to entry over time:

- Technology drives change in industries and an industry which has high barriers today may not have them tomorrow. If someone said 15 years ago they were going to make the biggest hotel chain in the world, you would have thought them crazy. Hotels cost huge amounts to build and doing so in every country would have been so capital intensive as to be impossible. Then Airbnb happened.

- Industries can go the other way – sometimes through technology or sometimes through managerial trends. Porter gives the example of how the automobile industry decided to vertically integrate, greatly increasing the barriers via newfound economies of scale.

Porter’s Five Forces – Force 2: Threat of substitutes

Substitute products here refers to products which can achieve broadly the same ends in meeting consumer needs, despite being different products.

I gave the example in reference to my mobile application of community-oriented Facebook groups. If the pricing strategies of language exchange apps were too high, consumers could turn to the Facebook groups to achieve the same needs for free. The groups might be less effective and meet only a fraction of the need but the perceived value is still there.

Porter gives the example of the fiberglass industry:

In 1978 the producers of fiberglass insulation enjoyed unprecedented demand as a result of high energy costs and severe winter weather. But the industry’s ability to raise prices was tempered by the plethora of insulation substitutes, including cellulose, rock wool, and styrofoam.

Substitute products of some form exist in almost all potential industries.

Porter concludes:

Substitute products that deserve the most attention strategically are those that (a) are subject to trends improving their price-performance trade-off with the industry’s product, or (b) are produced by industries earning high profits. Substitutes often come rapidly into play if some development increases competition in their industries and causes price reduction or performance improvement.

Any strategy you develop for your own products would have to be aware of what substitutes could exist for your end customers.

Porter’s Five Forces – Force 3: Bargaining power of customers

One of the key aspects in the model is the relationship between customers or buyers and suppliers.

When it comes to customers, the changes in what drives bargaining power can fluctuate in unexpected ways. It can be difficult to plan ahead as it’s hard to anticipate what will happen to customer expectation or preferred price points over time.

How much those changing expectations impact you determines what the bargaining power of the customer is. In the US, there’s an almost running joke that telecoms services are not good enough, yet the bargaining power of the customers is low and so the customers continue to buy what they perceive as substandard services.

What drives the bargaining power of customers?

A buyer group is powerful if:

- It is concentrated or purchases in large volumes.

- The products it purchases from the industry are standard or undifferentiated.

- The products it purchases from the industry form a component of its product and represent a significant fraction of its cost.

- It earns low profits, which create great incentive to lower its purchasing costs.

- The industry’s product is unimportant to the quality of the buyers’ products or services.

- The industry’s product does not save the buyer money.

- The buyers pose a credible threat of integrating backwards to make the industry’s product.

The above can be applied to either large commercial and retail buyers or even to consumer buyers. Porter adds:

Consumers tend to be more price sensitive if they are purchasing products that are undifferentiated, expensive relative to their incomes, and of a sort where quality is not particularly important.

Porter’s Five Forces – Force 4: Bargaining power of suppliers

But what about looking at it from the other angle? What constitutes the bargaining power of suppliers?

Very simply:

Suppliers can exert bargaining power on participants in an industry by raising prices or reducing the quality of purchased goods and services.

Suppliers have their own motivations and their own profit margins to worry about. Therefore, they can also take profit-maximizing moves which can impact on an industry.

What drives the bargaining power of suppliers?

A supplier group is powerful if:

- It is dominated by a few companies and is more concentrated than the industry it sells to.

- Its product is unique or at least differentiated, or if it has built up switching costs.

- It is not obliged to contend with other products for sale to the industry.

- It poses a credible threat of integrating forward into the industry’s business.

- The industry is not an important customer of the supplier group.

One of the themes behind the bargaining power of suppliers is their size and operations in a fairly uncompetitive space. We can see this in practice with companies like Foxconn. While there is significant competition in the global market for mobile phones – and other electronics – most companies in the space purchase from Foxconn at some point in their production. This dominance puts Foxconn in a position of high bargaining power.

For this reason, Porter highlights the bargaining power of a supplier as a particularly important part of the model. Unlike with the relationship with customers, where you can react to changing expectations via marketing, the supplier relationship is more baked-in to your business and much harder to change or break out of.

A company’s choice of suppliers to buy from or buyer groups to sell to should be viewed as a crucial strategic decision. A company can improve its strategic posture by finding suppliers or buyers who possess the least power to influence it adversely.

Porter’s Five Forces – Force 5: Competitive rivalry

Finally, we come back to the jockeying for position of the key competitors in the market space.

With the structural economic factors covered it now comes down to how each company chooses to position themselves and fight against the other players in the niche.

An intense rivalry within an industry is likely due to the presence of a few particular factors.

Influencers of competition in the space:

- Competitors are numerous or are roughly equal in size and power.

- Industry growth is slow, precipitating fights for market share that involve expansion-minded members.

- The product or service lacks differentiation or switching costs, which lock in buyers and protect one combatant from raids on its customers by another.

- Fixed costs are high or the product is perishable, creating strong temptation to cut prices.

- Capacity is normally augmented in large increments.

- Exit barriers are high.

- The rivals are diverse in strategies, origins, and “personalities.”

One example of competitiveness could be in the steel industry (Deloitte). There are many competitors in the global market, and though some are outsized there are many very large players. Equally, slow growth teamed with increased production in emerging economies presents opportunities for expansion for certain groups. Traditional barriers to switching costs for buyers (nationally strategic industries or incentivized local purchases) are mainly in place, but have been significantly lowered or removed in key economies: the United Kingdom, where British Steel entered insolvency after the government refused to support it. Yet exit barriers are very high, as most major economies look to support their steel industries even when they’re seeing negative return on investment. This is partly down to reasons of national security and partly due to the importance of steel in its role creating added value further down the supply chain.

So, as we can see after that long paragraph, most of those factors apply to some extent and you could probably make an argument for others too.

How you negotiate your competitive jockeying depends on your company’s specific situation.

Resolving the 5 Forces: An Economic Moat

Now that we have done our competitive position analysis, we need to figure out how to turn these insights into actionable approaches.

As Porter puts it:

[T]he strategist can devise a plan of action that may include (l) positioning the company so that its capabilities provide the best defense against the competitive force; and/or (2) influencing the balance of the forces through strategic moves, thereby improving the company’s position; and/or (3) anticipating shifts in the factors underlying the forces and responding to them, with the hope of exploiting change by choosing a strategy appropriate for the new competitive balance before opponents recognize it.

This basically comes down to, for example:

- Playing to your strengths

- Vertical integration

- Being ahead of the curve

Playing to your strengths is a bit of a conservative move, but that means a lower risk factor and can prove great for medium or even long term success depending on the industry. Vertical integration is a typical move for growing or large companies as they want to protect their market position, however, it comes with its own risks as you’re taking on production roles which you didn’t have previously – this is more often done effectively via acquisition but can be achieved in other ways. And being ahead of the curve is the riskiest of all; Apple’s iPhone gamble paid off where Blackberry’s didn’t. Both guessed the interface the future consumer would want but only one of them became a trillion-dollar company.

Figuring out how to protect yourself from competition has come to be referred to as developing an economic moat. The term was popularized by Warren Buffet and has a few components. You don’t need to tick every box – but you need at least one of these components to form your moat:

- Cost Advantage: Can you sustain lower costs than your competitors over a long enough period of time?

- Size Advantage: Are you big enough that your advantages from economies of scale protect you?

- High Switching Costs: Can you be so essential that it costs your competitors more to leave you than they could gain from others?

- Intangibles: Do you have patents or licenses other competitors require but don’t have?

- Soft Moats: Is there something else about you which gives an advantage? The customer service of Zappos, for instance, which is far beyond any industry standard.

By doing your research and understanding your competitive space you can craft a strategy which allows you to plan effectively for the future and bypass the industry’s difficulties. Or, if you’re an investor, you can use these approaches to determine whether or not there’s a long term future in this industry.

If you want to read some more Process Street articles around these topics, check out the posts below:

- Warren Buffet’s Investment Checklist – The Secret to His Success?

- What is TAM SAM SOM? How to Calculate and Use It in Your Business

- How 4 Top Startups are Reinventing Organizational Structure

- SWOT Analysis Template: What, How, & Why? (Free Template)

- Prioritization Matrix 101: What, How & Why? (Free Template)

- Production Systems: Why Tesla’s Gigafactory is Musk’s Most Ambitious Project Yet

- Agile ISO: A Holistic Business Process Management Framework

Or, if you want to use some of Process Street’s superpowered checklists to help drive your research in the future, check out some of these public templates:

- Warren Buffet’s Investment Checklist

- Business Partnership Due-Diligence Checklist

- Stock Purchase Due Diligence Checklist

- When to Sell Stocks Checklist

- FMEA Template: Failure Mode and Effects Analysis

- SWOT Analysis Template

- ISO 9000 Structure Template

- ISO 9000 Marketing Procedures

- Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) Template Structure

- Company Research Checklist

- Process for Improving a Process

- Ray Dalio’s Process Improvement Method

- Private Equity Due Diligence Checklist

- Product Strategy Template

- Product Launch Checklist

- Sales Pitch Planning Checklist

- Investor Pitch

- Financial Planning Process

- Annual Financial Report Template

- Financial Management For New Projects

- Startup Due Diligence for a Venture Capitalist

- Financial Plan Template

How do you conduct your competitive analysis? Do you use Porter’s Five Forces? Have you used Buffet’s economic moat approach? Let us know in the comments below!

Workflows

Workflows Projects

Projects Data Sets

Data Sets Forms

Forms Pages

Pages Automations

Automations Analytics

Analytics Apps

Apps Integrations

Integrations

Property management

Property management

Human resources

Human resources

Customer management

Customer management

Information technology

Information technology

Adam Henshall

I manage the content for Process Street and dabble in other projects inc language exchange app Idyoma on the side. Living in Sevilla in the south of Spain, my current hobby is learning Spanish! @adam_h_h on Twitter. Subscribe to my email newsletter here on Substack: Trust The Process. Or come join the conversation on Reddit at r/ProcessManagement.