After Elon Musk’s successes sending Falcon Heavy into space with his Roadster attached, the fanfare around his achievements has reached new highs.

After Elon Musk’s successes sending Falcon Heavy into space with his Roadster attached, the fanfare around his achievements has reached new highs.

But not everything is rosy for Musk.

Tesla is struggling. It’s not hitting its production targets for the Model 3, and this is not for the first time.

The goal for Tesla has been to hit 5,000 units per week and though Musk is confident of reaching that figure the Model 3 production has been mired by continually failing to meet demand.

It’s not enough just to have a good product, you also need to have high performing production systems in place to take that product effectively to market.

In this Process Street article, we’ll tackle the machine which builds the machine and we’re going to look at:

- What a production system is and what a good one looks like

- The production system of the future and how Elon Musk wants to build it

- Why a production system isn’t just for manufacturing

- How you can build production systems for your business

- Why Tesla’s Gigafactory is Musk’s most ambitious project yet

What a production system is and what a good one looks like

The term production system can refer to a range of different things. We’re going to focus on the nature of a production system within operations management.

In this sense, a production system typically describes the way an organization achieves its aims through combining technological elements like resources and tools with organizational elements like workflows and division of labor.

In manufacturing, for example, you put the raw materials into a production system and a product comes out the other end.

Let’s look briefly at some key terminology to help us:

Process production

This refers to taking a set of raw materials and performing a physical-chemical transformation on them. Once the transformation has occurred, it’s very difficult to get the raw materials back. You can think of the manufacturing of paper as falling in this category. You’re not going to turn it back into a tree.

Part production

This falls closer to the kind of systems we’ll look at throughout the article. This concerns the assembly of items to create a product. To make a car, you need to install windows and tires, to weld the engine and upholster the inside. These items will have been through process production in the previous stages; creating rubber for the tires, for instance.

Lead time

In short, lead time describes the time it takes between the placement of an order and the delivery of a product. If your competitor can create and deliver their product twice as fast as you can, then they have an advantage – provided quality is not lost.

Made to order

Imagine you’re in a restaurant and you place an order, this triggers a production process which results in you receiving your food. This kind of process is used for low volume or highly customized products.

Build to stock

On the other end of the spectrum, build to stock operates by setting a clear quota for production and aiming to meet that output. This quota will often be defined by historical demand or forecasted sales. This is the approach we see in mass market car manufacturing and is one of the core tenets of the shift in manufacturing approaches throughout the industrial revolution.

Assembly line

This is a production process where a product moves from workstation to workstation to be built step by step. This kind of progressive assembly often requires less labor expenditure as workers remain at their workstations and the product is moved from place to place.

The picture above depicts the early assembly lines of the Ford Model T.

Vertical integration

When a company owns all the steps of the manufacturing process, we call this vertical integration. In truth, it can be very difficult for the manufacturers of a complex product to be entirely vertically integrated.

Often we’ll talk about companies being more vertically integrated than others.

In Ashley Vance’s biography of Elon Musk we find a section dedicated to Musk’s identification of inefficiencies in NASA’s production system: NASA was paying extortionate fees to private companies to manufacture parts. SpaceX begun with the plan of being more vertically integrated than NASA in order to reduce production costs; the team built a much larger amount of their rockets than was normal in the industry.

Six Sigma

This is a process improvement methodology which works on the basis of understanding the number of defects in your products per every million produced. The number of defects per million defines what Sigma your production process is assigned. The goal is to reach a Sigma level of six, hence Six Sigma. You can read more in depth material on lean Six Sigma on our article about the DMAIC process.

Fordism

More than simply manufacturing terminology, Fordism now addresses the large scale social impact of an economic shift to mass manufactured goods. Henry Ford’s production processes for the Model T proved so efficient that cars were now able to be sold cheaper and therefore to more people. This mass production opened up the market for greater participation in consumer goods, spawning what we now know as consumerism. Fordism as a concept is often used to describe the way manufacturing processes, through mass production, changed the world.

The three widely associated principles of Fordism are:

- Standardization of the product so it can be made for stock.

- The use of assembly lines to speed up production.

- Paying workers well in order that they can participate in consumerism.

Toyota Production System

The Toyota Production System is seen as a set of best practices for manufacturing. Developed between 1948 and 1975 by Japanese engineers, the system is still evolving today. The concept of lean manufacturing is a more generic way to refer to the techniques and approaches pioneered by Toyota. There is an emphasis on analyzing the production process to optimize its performance.

It is based on three core principles: muri, mura, and muda. Or, overburdening, inconsistency, and eliminating waste. These principles are driven by a philosophy of continual improvement based around iterative gains; referred to as kaizen.

There are 8 kinds of waste Toyota want to eliminate from the process:

- Waste of overproduction (largest waste)

- Waste of time on hand (waiting)

- Waste of transportation

- Waste of processing itself

- Waste of stock at hand

- Waste of movement

- Waste of making defective products

- Waste of underutilized workers

You can read more about the Toyota Production System and related concepts in our detailed post on lean manufacturing principles.

Toyota is still the largest automobile manufacturer in the world, followed by Volkswagen, General Motors, Hyundai/Kia, and Ford. Toyota produced over 10 million vehicles in 2016 alone.

The production system of the future and how Elon Musk wants to build it

Though Tesla haven’t been hitting all their production targets during their relatively short lifetime, Elon Musk doesn’t seem too worried:

“The new automated lines will arrive next month, in March. It’s working in Germany. It’s going to be disassembled, brought over to the Gigafactory, reassembled and put into operation at the Gigafactory. It’s not a question of whether it works or not; it’s a question of disassembly, transport, and reassembly. So expect to alleviate that constraint. Alleviating that constraint, that’s what will get us to roughly 2,500 per week production rate.”

For Elon, any problems with production and the resultant media speculation are not his greatest concern. But why?

The automated lines he speaks of in the above quote are not just a one off addition to the factory. These automated lines are part of a larger project which is possibly more ambitious than any of his other quests – and this is a man who wants to meld the human brain with computers.

Musk’s Gigafactory aims to automate and optimize the production process to new levels; reducing human involvement and maximizing the speed of output.

In November 2016, Tesla completed the purchase of a German company called Grohmann Engineering. This obscure German firm are specialists in the development of automated technologies for manufacturing. Some of their legacy clients include Daimler (parent of Mercedes-Benz) and BMW.

Grohmann ended up becoming Tesla Advanced Automation Germany and 6 months into the relationship the original founder parted ways. The Verge report that this was caused by Musk wanting to end the firm’s work with outside clients and focus solely on Tesla.

Tesla’s plan was to add a further 1000 jobs to Grohmann’s existing workforce of 700; a massive increase in production potential now focused solely on one company.

Musk wants to work on the machine which builds the machine; to create a production system so advanced we’ll think of it as an “alien dreadnought”.

You can see a 7 minute video below of Musk speaking at a shareholders’ meeting about how we need to picture the production process as a product in and of itself. It’s a must watch.

Musk is taking a risk by building a production process from fresh rather than quickly iterating Tesla’s existing production process. However, the impact that might have on short term sales and output could well be dwarfed by the gains Tesla could get from revolutionizing the production process for future output.

As Musk points out in the video, he believes improving the production system could be the key to improving the business:

I actually think that the potential for improvement in the machine that makes the machine is a factor of 10 greater than the potential on the car side

Why a production system isn’t just for manufacturing

As we saw in the video above, Musk did a brief high level overview of the math behind the production process looking at how long it takes one unit to pass through the system. His conclusion was that this can be improved – we just need to find a way to do so.

For Musk, the way to approach and improve the issue lies in the machine which builds the machine.

But Musk isn’t the only person who has come to these kinds of conclusions via these methods.

If we take a wholly different kind of business, we could look at a company like Zappos. The online retailer sells shoes and clothing; it isn’t a super high tech manufacturing machine akin to car companies.

In a previous article on organizational structure, I took a look at the radical approach Zappos took to their organization and why they’ve gone so out of the mainstream. The basic premise is as follows:

When a city doubles in size, the productivity per person increases by 15%. When a company doubles in size, the opposite happens.

Zappos put this conclusion down to a number of factors, the primary one appearing to be the belief that larger cities encourage entrepreneurialism, whereas larger companies can inhibit those innovative advances. For Zappos, this meant reinventing their “machine”; looking at how the company operates and trying something new.

As Ethan Bernstein, Assistant Professor of Leadership in Organizational Behavior at Harvard Business School, puts it:

…[O]rganizations who are increasingly thinking about structure as an advantage and a form of making their employees more productive, will continue to evolve and innovate in this direction. And that’s something I think we’ll see across all organizations, regardless of whether they are trying to deliver “wow” to customers, or trying to do something very different.

The employees, rather than the machines, create the value in a company like Zappos so the production system must be one designed to maximize their output.

It might seem strange to think of playing with organizational structure as being comparable to iterating a production system, but these are simply different approaches to the same end: improving the product through a repeatable systemized means.

Ray Dalio, founder and CEO of Bridgewater Associates, describes in his book Principles how he built the largest hedge fund in the world.

For Dalio, a successful business requires effective systems and processes in order to thrive. The first mover in these processes are the principles you found the business with – and stick to. From there, your job is to build workflows which turn effort into work into output.

These workflows act as a production system for human organization; pushing papers rather than levers.

Production systems outside of manufacturing

We can see this demonstrated neatly in the world of fast food.

In a recent post on how franchises work, I looked at the rise of McDonald’s and their Speedee Service System. This system was the foundation upon which the fast food industry has been built.

From Taco Bell to KFC, the people within the McDonald brothers’ close circle went on to found some of the biggest fast food chains on the planet.

Why?

Why did one little collective from a fairly minor US city come to dominate the global fast food trade?

The Speedee Service System took the philosophy of industrial manufacturing and applied these production systems to the functioning of a restaurant. This resulted in higher output at lower cost per unit while also shaving off a range of related overhead costs.

This system could be replicated again and again – which made it so ripe for franchising and imitation.

In this clip from the film, you’ll see the story of how the McDonald brothers developed and improved their system with the help of a tennis court and a pack of chalk.

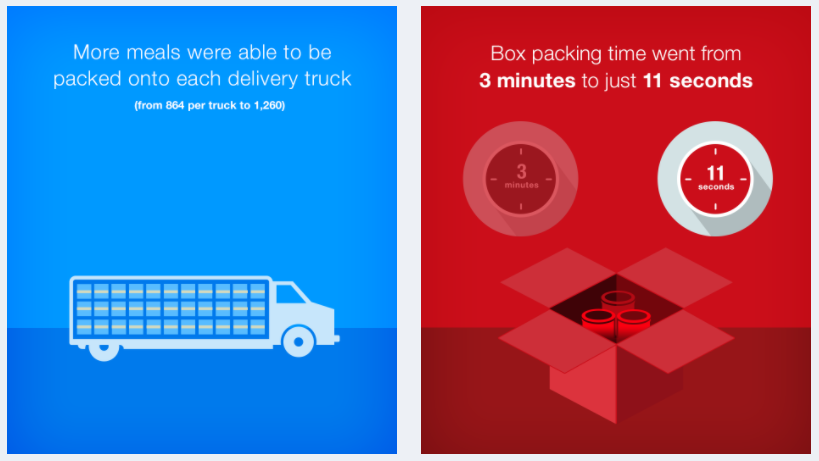

We can see a similar expression of this systemization in another video worth watching. This one comes from Toyota and is part of their scheme of trying to bring the Toyota Production System techniques to third-sector socially-beneficial causes.

The New York Food Bank is the largest food bank in the world and prior to the consultancy shown in this video, the team were struggling to meet the mammoth and growing demand for food parcels.

The Toyota consultancy team came in and implemented elements of their famed production system. This process implementation resulted in cutting the packing time per parcel down from 3 minutes to just 11 seconds, and cutting waste to increase the number of parcels per truck from 864 to 1260.

How you can build production systems for your business

Depending on your business, you’ll need to build different kinds of production systems with different structures and different goals.

Depending on your business, you’ll need to build different kinds of production systems with different structures and different goals.

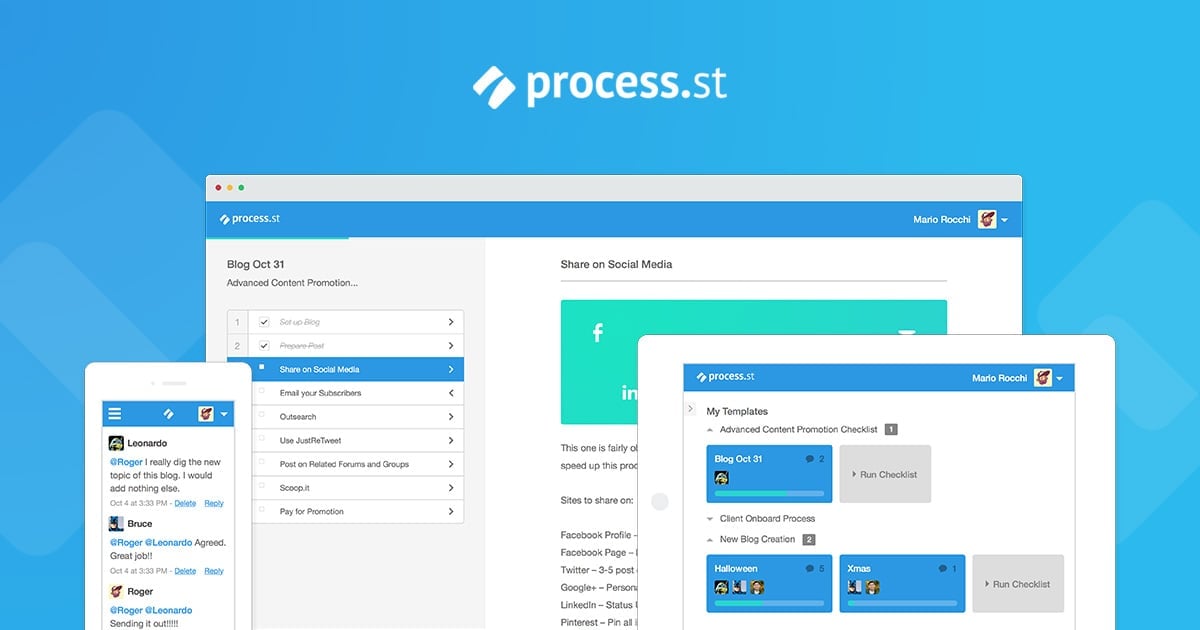

This is where tools like Process Street, and others like Lucidchart, can begin to play a role.

Lucidchart is a great visual tool to help you construct workflows through flow diagrams and build BPMN solutions for process mapping. This is a nice place to start modeling how your business operates and how your operations flow.

During this ideation phase, you can begin to understand from a high level overview the way in which the different segments of your business fit together.

Once you have this top down approach in place, you can drill down into the minutiae of the different processes and build them out in more detail. One approach to take is to document your workflows; write down step by step how you currently undertake different tasks.

This will give you actionable processes which you can follow, allowing you to standardize your business operations around your current best practices. This is roughly the same philosophy which underlies the use of standard operating procedures.

Process Street has been engineered to give users the ability to record these processes, store them in a single unified space, and run them in an easily actionable way each time a task is to be done.

You create your processes as templates and run them as checklists every time. The data entered into each checklist is then recorded in the Template Overview tab to be tracked and analyzed.

How Process Street can help you streamline your operations

We’re continually iterating and improving Process Street in order to allow for better systemization of your business.

Through our Inbox feature, each user within an organization can receive notifications when they have a new checklist or task assigned to them. This streamlines the experience of each individual and places their tasks in a centralized location.

With the addition of conditional logic, you can now build templates which show only the tasks relevant to the person running the checklist. If you have a sales workflow where the employee has to complete a different set of tasks depending on how a client answers a question, you can configure the checklist so that only the right tasks are shown once the response to that answer is entered; the rest remains hidden.

You can read more about the different ways you can employ conditional logic here: How to Use Conditional Logic: 8 Ways to Simplify Complex Processes

On top of all this, you can connect Process Street with the third-party automation platform Zapier to integrate your processes with the other platforms you use in your business.

Zapier has over 1000 different apps and webapps within its ecosystem and can allow you to remove time consuming tasks such as data entry from your workflows. The McKinsey report Four Fundamentals of Workplace Automation estimated that the average marketing executive could save 15% of their labor time through the use of commercially available automation technologies.

Finally, one aspect of the manufacturing industry’s approach to improving production systems has been the use of modular technology. Instead of building a factory fresh from the ground up every time, it saves time and money to take existing effective machinery and processes and to apply them to your own organization.

This increases start up time and accelerates operations. Here you’ll find an array of premade templates we’ve produced at Process Street which you can plug into your business and adapt to meet your needs:

- 4 Checklists to Perfect Your Client Onboarding Process

- HR Templates: The Perfect Pack for Company Success

- 6 Checklists to Perfect your New Employee Onboarding Processes

- 9 Checklists to Drive Your Sales Processes

- 7 Essential Design Processes & Checklists

- 11 Checklists to Optimize Your Accounting Processes

- 8 Electrical Inspection Checklists to Keep Your Workspaces Safe

- 8 IT Security Processes to Protect and Manage Company Data

- 12 Inspection Checklists to Maximize Safety in the Workplace

- How to Conduct an Interview: A Full Hiring Process With 11 Premade Interview Processes

These features can allow you to build and optimize your own business’ production system to create the most effective set of operational practices you can devise.

Why Tesla’s Gigafactory is Musk’s most ambitious project yet

Tesla aims to shift the world to electric cars. Its battery technology could even result in widely prevalent house batteries, decentralizing electricity grids and facilitating a truly green energy network.

SpaceX wants to make commercial space access and exploration feasible. Musk’s long term goal is to colonize Mars and make humanity a multi-planetary species.

SolarCity hopes to shift the world to green energy generation and wean ourselves off fossil fuels.

The Boring Company aspires to eliminate congestion, create the conditions for viable Hyperloop travel, and make New York to Washington DC a 30 minute journey.

Neuralink has the ultimate aim of being able to connect the human mind with a computer, allowing for an interface between the two.

So why am I proposing that the Gigafactory is the most ambitious project, given the science fiction goldmine above?

Most of these brilliant concepts rely on machines or machinery, which need to be produced en masse at reasonable cost in order to be both effective and commercially viable.

Fordism revolutionized society because of its impact on the economic base. The Model T did not revolutionize society, the factory which built the Model T was the prime driver.

If Musk is successful in achieving the fully automated high speed factory he dreams of then he will have built the machine to build all his other machines. Once the principal is in place and Teslas are rolling out the doors faster than Toyotas, next can come solar panels, spaceships, drilling machines, hyperloop skates, etc etc.

Musk, like Ford, wants to revolutionize the machine which builds the machines; and this, more than any one pet project, has the potential to drive humanity forward.

Is Elon Musk changing the way we think about production, or is he simply a bond villain with big ideas? Let us know your thoughts in the comments below!

Adam Henshall

I manage the content for Process Street and dabble in other projects inc language exchange app Idyoma on the side. Living in Sevilla in the south of Spain, my current hobby is learning Spanish! @adam_h_h on Twitter. Subscribe to my email newsletter here on Substack: Trust The Process. Or come join the conversation on Reddit at r/ProcessManagement.