I wrote a post about Shape Up, a development methodology, and you the reader wanted me to dive deeper. So, I did just that and interviewed Process Street’s Product Designer, Ivy.

I wrote a post about Shape Up, a development methodology, and you the reader wanted me to dive deeper. So, I did just that and interviewed Process Street’s Product Designer, Ivy.

Ivy answers common questions concerning how Shape Up works in practice, and although I briefly touch on the core phases of Shape Up’s approach, this post should be seen as a follow up to my original post which provides a full low-down of what Shape Up is and how it differs from alternative development methods like Scrum and Kanban.

So, make sure to read my last post on Shape Up so you have all the context you need for this post.

In this post, we’ll be covering:

- What is Shape Up?

- The makings of a Process Street Product Designer

- Shape Up from a Product Designer’s perspective

- Shape Up’s design process: Key takeaways

- The day-to-day Shape Up experience as Process Street’s Product Designer

Let’s kick things off with a brief re-cap of Shape Up’s key phases .

What is Shape Up?

Developed by Basecamp, a project management tool, Shape Up offers an alternative to other agile development approaches, such as Scrum or Kanban.

This section will touch on the core phases of Shape Up’s development approach. The section should be treated as a reference point for Ivy’s answers later in the post. Anything she mentions later is defined here.

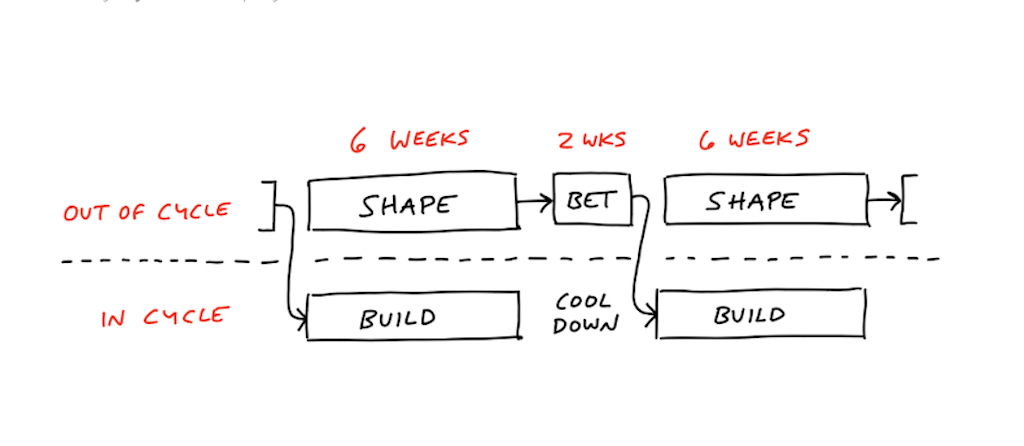

Cycles

A cycle is Shape Up’s version of a sprint. With Shape Up, you can have a cycle of 2, 4, or 6 weeks. Although, Shape Up suggests working in cycles of 6 weeks as it’s long enough to finish something meaningful and short enough to feel the deadline from the get-go. After each 6 week cycle, there is a 2-week cool-down period. After working hard to ship a project in 6 weeks, the cool-down periods are more flexible and allow the product teams to work on what they like.

Shaping

There are four parts to this process:

- Setting boundaries

- Roughing out the elements

- Addressing risks

- Writing the pitch

Ultimately, in the shaping process, you determine what it is you want to address in the next build cycle.

Betting

At the start of each cycle, there will be a number of pitches. To choose which pitch to run with, the Shape Up approach uses a betting table. This allows team members to choose which pitch they want to bet on for the upcoming build cycle. The more bets and the more superior the person betting, determine which pitch wins the bet.

Building

Cycles work on parallel tracks. Check out the image above for clarification. The upper track includes anyone who is shaping and/or placing bets, and the lower track includes those who are building. This means the team members who are shaping and betting run in unison with those who are on the building track. Building, as the name suggests, is the phase where the project for the cycle is built, by the product Engineers, Designers, or the EPD team (as is the case with Process Street).

Circuit breaker

The circuit breaker motivates teams to take ownership of their projects. It’s a risk management technique that involves canceling projects by default if they don’t ship in one cycle. It turns the tradition of extending by default on its head.

More resources

In 2019, Ryan Singer, Head of Strategy and Product at Basecamp, got the Shape Up approach down on paper in the digital book “Shape Up: Stop Running in Circles and Ship Work that Matters” which you can access here (it’s free). Alternatively, check out the Youtube video below:

With the basics covered, let’s move onto my interview with Ivy, Process Street’s Product Designer.

The makings of a Process Street Product Designer

Who is Ivy, what led her to Product Design, and Process Street specifically?

Hey, I’m Ivy, Senior Product Designer. Originally from New York, and currently based in Seattle. I started working in design almost by accident; I didn’t study design specifically. But, when I first moved to the Bay Area, Bettable (a gambling platform) needed an illustrator and that was my specialty at the time. I started off as an illustrator and over time they gave me some graphic design work, and then they gave me the opportunity to hop into product design.

The really scary thing about that was that they had two product designers at the time, but then they both left; leaving me to hold the reins as a newbie. However, the upside of that was it gave me a lot of opportunity to grow without anyone holding my hand. I was left to do the design work autonomously, so I learned a lot in a short period of time.

It was also at Bettable that I got my first taste for the startup life. I like startups because I enjoy working on something that is up and coming, this also drew me to Process Street.

When did you start with Process Street?

August 2020. Along with heaps of other people. Because we’ve expanded so much, we have a lot of new people on the EPD team. But in a way, I think this is a good thing (more on that later).

What was your experience at other startups? And how does the Process Street experience compare?

After Bettable I went to Zeus, which was a midsized dating company/ app based in San Francisco. Zeus had a six-person design team. After that, I went to Carvana, which is a massive company here in the US. At the time it had about 3000 employees. Their design team was huge and had at least 15 people.

At Carvana, I was integrated into the team as a UI designer. But, the way Carvana did things was to operate almost like a mini agency within the Design team. So, they had project managers and different sets of teams for UX designers and UI designers.

The way that works is a UI designer designs the interface that people see, and the UX designer designs the flows, the interactions, or the experience of how someone uses the product. They’ll usually work in wireframe and then the UI designers use that as a blueprint to create the final UI design.

What this meant was the workload was pretty divided. Whereas at Process Street, the structure is completely different.

At Process Street the role is “Product Designer” which means that all the roles that were divided up at Carvana, are packed into one. I do them all. That was specifically what I was looking for.

Here at Process Street, I work directly with the Product Manager, Michael. We get together twice a week to jam on some ideas, exchange feedback, brainstorm things we’re unsure about, and go over upcoming features. At Process Street, I work very closely with the Product Managers, whereas at Carvana, it was more like “here’s a task, go do some work, then come back to me for feedback”; more of a distant exchange. In contrast, with Process Street, Michael and I work very closely together.

The same goes for the engineers. In every other role, including Bettable, but especially at Carvana, there was a lot of division between the Design team and the Engineering team. They were completely separate teams.

![]()

“Process Street is the first team I’ve had where Engineering, Product, and Design all work together. That’s why they call it the EPD team.”

Not only do I work very closely with the Product Manager, but I also work very closely with the Engineers. We hop on a stand-up meeting with Herbie and all the other Engineers that I work with on projects.

Right now, seeing as I’m the only Designer, I’ll attend two team stand-ups for each of the squads who are currently working on projects. During the meetings, I’ll answer questions and I’ll show my work to them, so it’s a much closer collaboration between disciplines than I’ve done in the past. Which is exactly what I was looking for.

We’ve expanded so much over the past year. How do you find working on the product team with so many new team members?

It’s interesting because, at the same time as people have been coming in, a few people have left. Madison (ex-Product Manager) being one of them. She’d been here for 4 years and was a Process Street expert. The team went from having a complete expert to having a group of employees that were still kind of figuring things out.

But in a way, it’s almost a good thing because I think sometimes you can lean too much on old ideas of what the product was. However, by coming in with fresh eyes you have newer perspectives; perspectives that are similar to the customers who are completely new to Process Street. We newbies see it in the same way they do.

Everyone I have talked to who is newer to the company was confused about what the product actually was coming in. I think that experience helps us newcomers shape the experience better for new customers down the road.

Shape Up from a Product Designer’s perspective

![]()

“What really worked well was putting a strict timeline on projects. A very common problem throughout the tech industry is that you start a project and then people keep adding scope onto it.”

From a Product Designer’s perspective, what worked well?

Strict timelines on projects mean that the problem of constantly adding scope is avoided. Normally, in tech, you’d show something to someone and they’d say “Oh, what about this…” and then before you know it you’re spending months getting something out. I’ve been on so many projects like that.

I think what really is great about Shape Up is that you have 2, 4, or 6 weeks (cycles) to do a project and you have to ship it out by then. At the end of a cycle, you have what’s called a circuit breaker and after that you have to drop the project if it isn’t completed.

At Process Street, we aren’t super strict about the circuit breaker. For example, for the Slack and Process Street integration project, we allowed another week. Given that there were good marketing opportunities there we thought it extra important to get it in shape to present to Slack. That said, in general we try to adhere to the circuit breaker as much as possible.

Shape Up allows space for us to say if we don’t feel that we will complete a project within the cycle. The circuit breaker means we can choose to drop it. Pre-Shape Up, I always experienced a lot of back and forth amongst teams as the feature or project might be more important to some people than others. With Shape Up, we’re given the power to say “no, I don’t think this works for this particular cycle”, or we just don’t have time to do it/do it well. We can choose to cut the project for now and come back to it later which is really great.

When it comes to choosing what to run with/cut, who is involved in the decision making process?

This is something we do in the building phase. During this phase, everyone makes a decision together. For example this morning, Herbie the Engineer sent out a message saying he didn’t think we should develop a certain feature within this cycle because there were technical limitations that would make it very difficult. So later today, the EPD team will come to a decision together about what they want to do about the feature. It’s rarely unilateral. If a feature were to be cut, there should always be a good reason behind it.

Side note: Betting is mainly done by Michael and Ryan the Product Leaders, that’s when they choose the projects that we (the EPD team) will be working on within the cycle.

What didn’t work so well?

The first cycle we did took some adjusting. For one, we allowed ourselves too little time to get the project shipped. We saw that Shape Up recommended 6 weeks, but thought that was too much time and that we’d run with a 4-week cycle instead. We basically allowed ourselves too little time and then we couldn’t ship the project in 4 weeks.

I think there are also some blind spots in Shape Up that they don’t really prepare you for. Such as there is no real phase for discovery. Discovery is where you dedicate time to thinking through the problem, the flow, the implications of the feature, and how it would work in the user experience. That doesn’t really officially exist within Shape Up so we didn’t allow a lot of time for that, because we were following the book as close to the letter as we could.

As a result, we had the Engineers start developing on a feature and then realized, when it was in development, and after they’d done work on it, that the feature just simply wouldn’t work. This meant the Engineers had to discard the work they had done on the feature.

This could’ve been avoided if we had done a bit more work on the discovery phase. As a result, we now have a process called “Certification” which is where we decide concretely on what we’re going to build. This allows us as Product People to think through the implications of a problem. It also provides the Engineers a chance to do discovery of their own so they can research technical bits, like libraries and tools, that they could use to build stuff. I think Certification gives us more time to plan for the cycle, within the cycle.

Certification is a Process Street thing as far as I know. Not officially part of Shape Up’s development methodology. Although, Shape Up does imply that some form of discovery is needed within the building phase. Process Street expands on that with Certification.

What surprised you?

I was surprised that we were able to get something out so quickly. This is not usually the case in the tech world, projects get bogged down by scope creep, by deliberation, and so on. The fact that we were able to get out this significant change to the templates page in 4 weeks was incredible to me. I rarely ship things to completion that quickly. Usually, even smaller UX changes or larger projects that take months to push out.

At Carvana, I worked on something that took a full year to ship from the moment that I started working on it in the design phase to it being shipped out to customers. That’s what I was used to before Shape Up, things taking months or even years to ship.

The fact that we can get something out that makes an improvement to the UX in such a short period of time is just amazing.

What was hard about the adjustment/what was easy?

It wasn’t personally hard for me because Shape Up plays really well into the way that I prefer to work, which is very snappy and from the hip. I prefer to go with the flow and address problems when they come up, which is the way Shape Up works. Even if you do Certification like we currently do, things will still crop up that you don’t expect. Such as the comment made today.

I think Shape Up will help you naturally transition to an adaptable way of thinking, that flows so you can address problems as and when they come up. No matter how prepared you are, you can’t possibly account for everything. I feel very comfortable working within this kind of space and I think Shape Up is a great fit for me.

How did you convince the EPD team to just abandon a feature when it isn’t done in time?

I’m not usually the one to make this call. But, if we go back to the first cycle we ever worked on, that’s a good example of how Shape Up provides you with an opportunity to stop a project. Midway through the building phase and towards the end of the cycle, the EPD team got together to go over all of the implications and how long it would realistically take to finish. And together, as a team, we realized that there just wasn’t enough time within the cycle to ship the feature.

The day-to-day Shape Up experience as Process Street’s Product Designer

![]()

“Building is when I start to be more actively involved. Sometimes I’ll start working on designs ahead of the building phase just so that we can hit the ground running”

Walk me through Shape Up, as experienced by you, Process Street’s Product Designer …

Shaping and betting are when we as a team decide what projects were going to be working on within a cycle. This is typically led by the Product Leads; they are the ones that write the pitches and describe the features we might build. I’ll often contribute by helping the Product Lead flesh out ideas or visualize them better. I might create a basic mockup for him, or make suggestions. Overall, shaping and betting is mostly led by the product leaders.

The building phase is when I’ll start refining parts of the design, I’ll format and organize the designs so the engineers can focus on what they need to do. I’ll annotate things and point out what changes are being made. Likewise the product people or engineers can point out where I should spend more time, what needs fleshing out, and so on.

The way we approach it is that we start with a design that’s about 60 or 70% there/done. Then the Engineers will start working on it. As things start to crop up, I’ll work on those specific parts of the design to better clarify what wasn’t clear the first time around.

It seems like it’s a real group effort following Shape Up’s approach. What was it like before the team moved to Shape Up?

At Process Street we already had the EPD team, so we were already working quite closely together. One big change is that we’ve massively cut down on our meetings. Before we had heaps of meetings to build consensus, for stand up, and to talk things over. I don’t even remember what they were all for, but we had a lot of different meetings!

I think the fact that Shape Up is so directed and each cycle is so specific allows us to have less meetings, more focus time, and to really get into the stuff that we’re working on. The direction that Shape Up offers really helps to minimize the levels of ambiguity. This means that there is less need for lots of meetings. Everyone knows what the goal is and what their role is in achieving that goal. We can do a lot more work asynchronously as opposed to spending all of our time in meetings.

Do you have any tips/hacks for any Product Designer’s considering making the move to Shape Up?

I think for some people it will be more of a transition than it would be for others based on your team’s structure. If your design team is very separated from your other teams, then it will be significantly more difficult. That said, if you want to be successful in Shape Up, you have to be comfortable with working very closely with engineers and taking their feedback.

You can’t work in a silo with Shape Up, at least I don’t think you can do it successfully. You have to take things as they go, and be ready to go with the flow and be aware that things will crop up that you aren’t prepared for. Another major thing is being comfortable in saying no, and being aware of the engineering cost vs what is necessary for the design.

Shape Up’s design process: Key takeaways

- Learn to say no, and be ok with it. ♀️

- To be successful, you need to embrace the power of the team.

- Say goodbye to meetings and work asynchronously.

- Consider adding Certification to your Shape Up process to give yourself more time to plan for the cycle within the cycle.

- Be adaptable, and go with the flow.

Thanks Ivy!

The Shape Up approach is still fairly new for us at Process Street. Despite this, it is already working wonders. We’ve cut our development cycle by 70%, the EPD team have ditched unnecessary meetings, and as an outcome of this, they have heaps more focus time. Simply put, Shape Up helps us to ship, and ship quickly.

P.S: Don’t forget to subscribe to the Process Street blog to get notified of our upcoming articles. We also have a podcast “Tech Out Loud” featuring content written by respected industry leaders such as Peep Laja, Sujan Patel, Tomasz Tunguz, and more!

Did you find this article useful? Do you have any questions left unanswered? If so, let us know in the comments below! Who knows, maybe we’ll answer them in another follow-up post!

Workflows

Workflows Forms

Forms Data Sets

Data Sets Pages

Pages Process AI

Process AI Automations

Automations Analytics

Analytics Apps

Apps Integrations

Integrations

Property management

Property management

Human resources

Human resources

Customer management

Customer management

Information technology

Information technology

Molly Stovold

Hey, I'm Molly, Junior Content Writer at Process Street with a First-Class Honors Degree in Development Studies & Spanish. I love writing so much that I also have my own blog where I write about everything that interests me; from traveling solo to mindful living. Check it out at mollystovold.com.