Greek philosophers can teach us a great deal. Let’s, for example, take this quote:

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it” – George Santayana

Big George, originally Jorge, makes a valid point with this one. The quote is often used to talk about giant historical shifts or wars or something similar. Yet, it’s equally true of smaller things.

In business, as in life, someone has already come before you and done the same thing. These people have failed, learned, and then improved. We, in the future, are in the fortunate position of being able to learn from their failures and successes if we choose to.

And this is why we choose to bang on about the past so much. Whether it be recent history like The History of SaaS, 20th Century history like How Does a Franchise Work?, further back like The History of Surgical Processes, or even further back to the beginnings of civilization like How Were The Pyramids Built?, we often like to take lessons from the past.

In this Process Street article, we’re going to ancient Greece to check out 9 key philosophers and see what business lessons we can take from their lives and work.

Who are the Greeks and why are they important?

Firstly, let’s just get the basics out of the way.

Ancient Greece wasn’t really comparable to nation states of today or even to the Roman Empire, given that there was no one unified nation or organization of Greek speakers.

What we refer to as Ancient Greece occurred around the period of 800 BC to 300 BC, and a little later possibly. But it’s difficult because it’s a surprisingly disparate concept. As Edith Hall describes in The Guardian:

Greek-speakers lived in hundreds of different villages, towns and cities, from Spain to Libya and the Nile Delta, from the freezing river Don in the northeastern corner of the Black Sea to Trebizond. They were culturally elastic, and often freely intermarried with other peoples; they had no sense of ethnic inequality that was biologically determined, since the concepts of distinct world “races” had not been invented. They tolerated and even welcomed imported foreign gods.

Hall points out that the closest we can find to a unified Greece would be Alexander the Great’s strong but short lived Macedonian Empire.

This also means it’s important for us to recognize that the “Greeks” were to result in the Roman Empire to the west, the Seleucid Empire to the east, and the Ptolemaic Empire to the south. We should refrain from taking a solely Western perspective on Greek thinkers; a narrative which often feels entrenched.

Nonetheless, Greek thinkers contributed hugely to our understanding of the world.

Our understanding of ethics, politics, mathematics, and the natural sciences owe a lot to our ancient thinkers. Much Greek work was reintroduced to what we now think of as the West via increased trade with the Middle East across the 10th and 11th centuries onwards.

Great early thinkers like Thomas Aquinas merged Catholic theology with Platonic thought, while later philosophical giants such as Hegel drew heavily from Aristotle’s work.

There has always been a great deal to learn from the world of the Ancient Greeks.

That said, let’s kick off with my main man, the big dog…

Socrates believes in talking problems out

I want to apologise firstly for that gross over-simplification. It’s not so much that Socrates calmed people down with his soothing voice, but he believed that the route to truth was the dialectic.

Not Hegel’s dialectic or Marx’s dialectical materialism. Socrates thought that being in conversation helps you work issues out by inspecting or analysing another person’s point.

We have this idea of Socrates because we only know him through the writings of Plato (and Xenophon) where’s he’s always in discussion with other philosophers. Current consensus is that early Plato is a representation of the actual Socrates while late Plato is a kind of Socrates fan-fiction where Plato uses the characters to espouse his own thoughts.

Plato’s Republic is pretty much a comic book about an invincible man named Adeimantus who keeps striking out at people. I’m not pointing fingers but Roy Thomas is a fraud and Stan Lee knew.

We call this slightly competitive verbal jousting the Socratic Method, elenchus, in his honor. It’s this emphasis of dialectic over didactic which we can take away as a business lesson. The focus on finding truth through the exchange of logical arguments can be better than a more instructive approach.

In a practical business sense, when you want to improve a business process you don’t just sit down to redraw the process and then impose it on employees. Instead, you take the time to talk to the employees about the pain points and to suggest process changes and to listen to their suggestions. You develop new processes and workflows through that discourse. Then you can use checklists or whichever method within the organization which people will actually want to follow.

The massive banker Ray Dalio is a big believer in this. He’s founder and CEO of Bridgewater Associates – one of the biggest hedge funds in the world. In his book Principles, he talks about his concept of Radical Truth. Everything in his company must be ironed out through discussion in order for employees to find truth to act on.

Plato thinks your ideal product is out there somewhere

One thing Plato was big on, other than recording old men, was an idea called Forms.

Plato proposed that there was an ideal version of a concept to which all material versions relate.

Like, there is a pure idea of a chair. That idea of the chair is what gives all other chairs their chairness.

Plato brings these ideas out through the character of Socrates with the idea that the truest form of knowledge is attained through the study of the Forms. So for Plato, the tip top knowledge comes from trying to understand what the ideal Form is of each concept. The pursuit of a knowledge of the Forms is a noble endeavour.

And this… wait for it… is at the heart of any lean methodology.

Okay, not just lean but it’s easy to see it there. When you first develop a product, you will often develop a Minimum Viable Product (MVP); something which serves the basic need your product wants to serve. Yet that product will change over time.

It will develop as it interacts with the public and as you gather their feedback. As you attain greater resources you’ll make improvements and iterations – maybe even an entire rebuild!

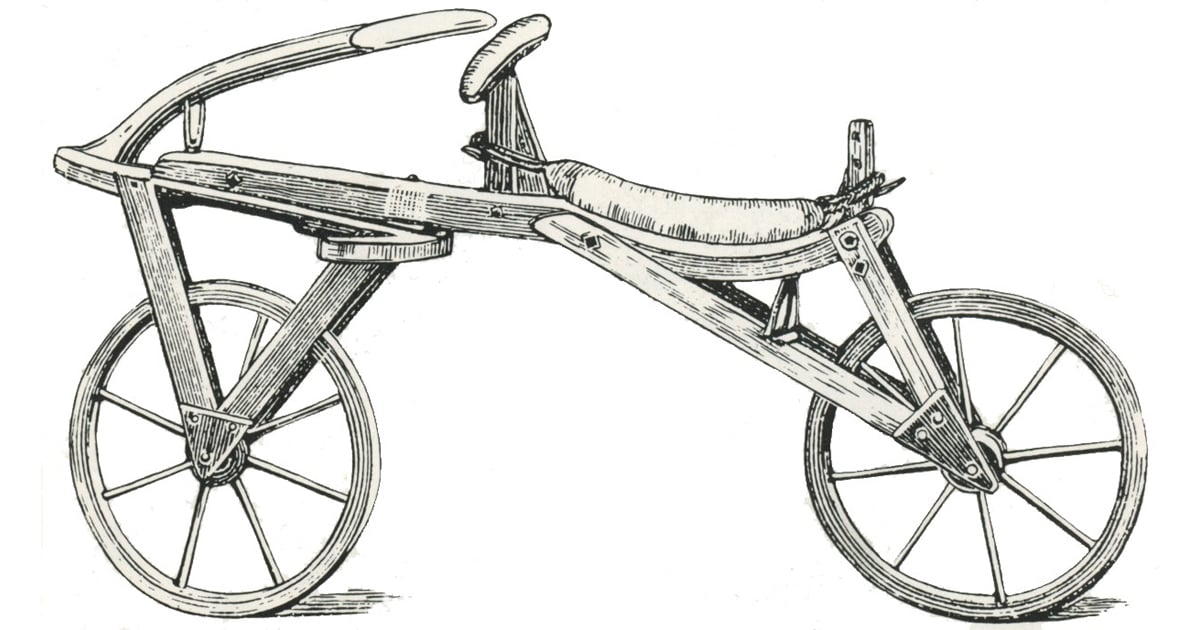

The first ever bicycle was called a Dandy Horse. That has now evolved over time into the modern bicycle and every variant of it. Though, the purpose of the Dandy Horse was to help people get around faster. To go from A to B in comfort and at speed.

Maybe the Form which the Dandy Horse corresponds with isn’t a bicycle at all? Maybe it’s a luxurious 1997 Ford Ka, the most nimble way to get around yet invented by humanity? Or maybe I’m stretching this a little…

In the eyes of Plato, there exists an ideal version of your product in the Forms and your quest will take you closer and closer to the true product.

The same is true of anything you want to construct or improve. You don’t know how a process is meant to look until you’ve built it, used it, and found what’s wrong with it.

Zeno of Citium would be a ruthless CEO

Zeno was a stoic and widely considered the founder of stoicism. The word stoicism comes from the term Stoa Poikile which was just a porch on the north side of the agora in Athens. Zeno and the lads would hang out there to discuss cynicism and enjoy street poetry, and the name stuck.

Stoics generally believe in a kind of living in the moment personal philosophy – that we shouldn’t be too caught up with desires for pleasure or fear of pain. They are big on the idea of something called Virtue Ethics, which is a school in moral philosophy which prioritizes having good moral character – unlike deontology which is all about following rules or consequentialism which determines whether something was good or bad based on the outcome.

Zeno liked categorizing emotions and strangely put pleasure (hêdonê) in the bad camp and caution (eulabeia) in the good camp.

He comes to this conclusion because the man loves Reason. If something seems to adhere to Reason it goes in the good and if it doesn’t it goes in the bad. And he was very strong on this one.

If something is slightly bad then it is completely bad. It should be got rid of.

While this sounds a little extreme, using reason to root out problems is a pretty important thing to do. If something is only a little bit bad it can still cause a massive risk or error.

When NASA launched Challenger they were aware of problems with the joints on the SRBs, yet they launched anyway. The whole crew died.

This disaster lead to Diane Vaughn coining her concept of the normalization of deviance. This is where poor processes get normalized in an organization to the point where the members of the organization can’t see their own errors.

Zeno would find these problems and tackle them head on. There is no space for errors or poor processes in Zeno’s business. If it’s not good, it’s out.

Democritus reminds us to pay attention to the little things

Democritus is sometimes referred to as “the father of modern science”. Which, I’ll be honest, is very generous considering the lack of causal relationship between him and early pioneers of science like Francis Bacon et al.

The pre-Socratic philosopher whose name would suggest he pioneered Democracy – he didn’t – was detested by Plato who reportedly wanted all Democritus’ books to be burned.

We actually don’t know a great deal about Democritus or his body of work as, like so many Ancient Greek philosophers, his writings were largely lost to history.

Nevertheless, he is most widely renowned for his role as one of the early atomists. I’ve made a controversial decision including him here given that early atomist theory was more likely rooted in Leucippus, but Democritus takes much of the credit for the conception of the atom.

There isn’t too much point going in depth on how Democritus imagined atoms to work, or how they would be categorized, as it’s obviously scientifically inaccurate. He believed iron atoms would have the properties of iron, and water atoms the properties of water; slippery and smooth.

What is important is that these early atomists theorized that all substances were made up of tiny indivisible parts, too small for the human eye to see. And, that the nature of these tiny indivisible parts contributed to the properties of the larger whole which they formed.

Democritus, in that sense, reminds us that a successful business is not just a good idea.

Anyone can have a good idea. A good business needs to pay attention to the details.

In modern businesses, teams of process specialists will help other departments in the company to make iterative improvements on their regular and occasional processes. These small tweaks and benefits will result in fractional gains.

Fractional gains may not sound huge but cumulatively they can reap massive results in regard to output.

How HubSpot turned fractional gains into big recurring increases

In a previous post about user onboarding, I talked about HubSpot’s product Sidekick and how the company drove revenue upward through improving the user onboarding process.

HubSpot had about a 10-15% retention rate by week 10 for their Sidekick product. Once someone had been retained by week 10 they tended to keep using the product. The goal was to increase that week 10 figure.

HubSpot decided to focus on the details of the week 1 onboarding and with a series of small iterative improvements managed to increase week 1 retention from somewhere in the 60s to 75%. This small increase in week 1 retention resulted in a massive jump to 25% week 10 retention.

Meaning that the Sidekick product had practically doubled its revenue simply by increasing week 1 retention by less than 15%.

A strong business functions well in all its aspects and operations, and does so by paying attention to the details. A large whole is made up of lots of small parts. In many ways Democritus was right that the properties of the small parts determine the properties of the whole.

Diogenes looked at society from the outside

I couldn’t write about Greek philosophers without including everyone’s favorite; Diogenes.

Diogenes lived in Athens during his glory years before being captured by pirates and sold into slavery. He eventually ended up in Corinth where he taught the aforementioned Zeno of Citium.

This fella was a character. He wanted to live a life of virtue and criticized the cultural and social norms of Athens, ultimately attempting to live a life outside of those norms. His experience as an outsider within society gave him surprisingly valuable insights which challenged conventional Athenian thought.

Diogenes lived homeless, sleeping, eating, and defecating wherever he pleased. His favorite sleeping spot was in a large ceramic pot in the marketplace. He was prone to public masturbation, allegedly saying:

If only it were as easy to banish hunger by rubbing my belly.

But it wasn’t all defecation and masturbation for Philosopher Di, the people’s philosopher. He had a series of profound critiques of interpretations of ethics and of the reasoning of major philosophers of the time.

Diogenes advocated virtue, simplicity, and nature, criticizing Plato for his moral abstractions. Plato, in response, described Diogenes as:

A Socrates gone mad

Diogenes would criticize the moral character of the Athenians by walking around during the day with a lamp, declaring when asked:

I am just looking for an honest man.

Yet his removed position from the Academy meant he could see problems and holes within some of the claims being made by established philosophical thinkers. When Plato described man as a “featherless biped”, Diogenes plucked a chicken and burst into the Academy, exclaiming:

Behold! I’ve brought you a man

All this is a very long winded and tenuous way to suggest that Diogenes was an outsider who disrupted the established thought of the age. His outsider status led to him being considered the founder of Cynicism and influencing Zeno to found Stoicism. His contribution to Greek thought shouldn’t be understated, no matter how absurd the stories are.

Looking at a set of established thoughts and seeking to disrupt them with something new is a timeless part of business. Some businesses iterate on previous models while others tear the models down and start fresh.

Greek philosophers or Silicon Valley innovators?

Peter Thiel, in his book Zero to One, talks about the importance of big ideas and how they spring up from outside the established modes of thought within an industry.

You can see, in the businesses of Thiel and Musk, a willingness to approach an established order with a wholly new take. In their X.com/Paypal days they pioneered the use of the internet for making and receiving payments.

Musk even more notably went on to try to bring electric cars into the mainstream, to make solar panels a major player in energy production, to revolutionize the space industry, and other massive challenges. All of which are having seemingly a fair bit of success.

By targeting innovation – Thiel’s idea of zero to one – companies like this don’t just pander to a niche in the market, but set themselves up to dominate markets by being ahead of the curve – or even starting the curve!

Uber, Airbnb, Ebay.

These are all zero to one companies. The Airbnb founders were not hotel magnates. Uber founders were not car manufacturers or taxi kingpins. The Ebay founders were not master-garage sale merchants.

Yet whole industries were disrupted by outsiders with bold ideas.

Now, I’m not saying that Elon Musk is a modern day Diogenes, but it is important for entrepreneurs to try to take fresh looks at established thinking and to sit in the place of the outsider every now and then.

Epictetus teaches us to deal with failure

While Donald Trump advocates for never getting tired of winning, the Ancient Greek philosopher Epictetus teaches us to never get tired of failing.

Well, it kind of depends on how you’ve failed.

Epictetus was one of the Stoics and not actually an Ancient Greek thinker. Sorry. He was a Roman era thinker born a slave in modern day Turkey and lived most his life in Rome until being banished to Greece.

His perspective was that philosophy is something to be lived, not simply thought about. He believed in a radical program of self-improvement. This was centered around the idea that you only have control over yourself.

You cannot control for external circumstances, only your own actions. Given this, it made obvious sense to Epictetus that trying to improve yourself wasn’t merely an option but a moral responsibility. This formed the cornerstone of his Stoicism.

Epictetus, and his branch of Stoicism, should be read and considered by any aspiring – or established – entrepreneur.

Very few people will have success with a startup on their first try.

According to Forbes, Cambridge Associates report that 60% of venture backed startups fail each year. That number is even higher if you include startups which failed to grab venture backing. Another Forbes article claims 90% of startups fail in their first year.

But as Epictetus teaches us, failure can be a good thing. It helps us grow and encourages us to be more rigorous with ourselves – whether working harder, learning new skills, or just changing our approach.

Christina Wallace described to Fast Company what happened after her startup died after just 10 months:

After it was all over I spent three weeks straight in bed. Then after 21 days of sleeping, crying, I put on my big girl pants and rejoined the world. Startups are not just what you read in the press. The real story is much more volatile and human, and we do our community a disservice pretending otherwise.

You can’t control all the external factors in your life. But you can work on yourself and improve.

Epictetus knew it over 2000 years ago. You know it too.

Epicurus loved developing company culture

Epicurus was a fairly interesting philosopher in that much of his surviving work is championed by people who like to discuss whether God is real or not, or whether heaven is real or not. Most famously, IMO, in 1779 by David Hume:

Epicurus’s old questions are yet unanswered. Is he willing to prevent evil, but not able? then is he impotent. Is he able, but not willing? then is he malevolent. Is he both able and willing? whence then is evil?

This atheistic stance has led to many appearances in popular culture throughout the years, including a cheery cameo for Epicurus and his materialistic followers in a book called Inferno by Dante. You can probably guess how the story pans out.

He also makes an appearance in the prologue for Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales in a description of the character Franklin (Frankeleyn):

Wel loved he by the morwe a sop in wyn;

To lyven in delit was evre his wone,

For he was Epicurus owene sone,

That heeld opinioun that pleyn delit

Was verray felicitee parfit

The character above likes bread soaked in wine and holds the opinion that pleasure (read: plain delight) was perfect happiness. This materialism was seen as very Epicurean.

Given that Epicurus was so big on people having pleasure and fun, it should be no surprise that he liked to cultivate a company culture where everyone was able to enjoy themselves.

And he actually did just that.

In Athens Epicurus bought a property in order to start a school. The school was called simply Garden – very Silicon Valley. The school is believed to have been one of the first to admit women as standard and it even had a company mission statement above the door:

Stranger, here you will do well to tarry; here our highest good is pleasure.

Not as catchy as “Don’t be evil” but it was still there to be recorded by Seneca the Younger during the Roman times, so I guess it lasted longer.

Epicurus and his followers at the Garden promoted friendship as a moral good and sought to create a community whereby like-minded individuals could learn and work and grow together. In the end it sounded like it became a bit of a cult, but no one’s perfect.

How Ray Dalio designed his Garden

In Ray Dalio‘s book Principles, he discusses how he constructed company culture at Bridgewater Associates; starting, as Epicurus did, with key foundational principles:

- Radical Truth – Think of this as the supreme importance of truth at all times.

- Radical Transparency – Answers can only reach truth if they have all the information and data available to them. Transparency, in this sense, facilitates truth – particularly when managing people.

- Getting in Synch – Creating shared truths which teams can operate around to maximize the effectiveness of these truth-realizations in a practical sense.

This was rooted in a very Epicurean manner in the idea that truth is discovered collectively, therefore there should be a collective push toward truth. As Dalio puts it:

Being truthful, and letting others be truthful with you, allows you to explore your own thoughts and exposes you to the feedback that is essential for your learning. (pg.56)

A good company culture makes people happy, increases retention, and encourages people to work harder and better. If Epicurus can achieve that nearly 2500 years ago, then you can too.

Whether your accounting department will build you a statue remains to be seen…

Pythagoras would absolutely love Big Data

We all know who Pythagoras was. We learned that in school, right?

Well, there’s a good chance Pythagoras didn’t actually come up with that theorem himself. In Walter Burkert‘s 1972 text Homo necans, he reveals that the evidence for pythagoras having been responsible for all of these discoveries himself is slim.

This is why you shouldn’t have heros, kids.

Nonetheless, if we take a fairly blinkered view of Pythagoras then we can pull out some business comparisons.

We have to remember that Pythagoras was born over 100 years before Plato. The work of Pythagoras (and perhaps his team) was crucial to shaping the rationalist conception we have of the Greek thinkers. So Pythagoras’ broader work has a lot of Mysticism in it, and would sound pretty silly to us.

Aristotle, for example, claims that Pythagoras and his followers were great at maths but had no desire to employ it practically. Their mathematical discoveries were more of a religious experience than how we conceive of maths.

The Pythagoreans loved the number 3 because it had a beginning, middle, and end. But 3 had some stiff competition in 10, which the Pythagoreans thought was the ideal number. So good was the number 10 that Pythagoreans would never gather in groups of more than 10.

They had discovered a new tool and they were pretty good at using it, they just hadn’t figured out what it was best to use it for.

It would be like going back in time and giving the Ancient Greeks a combine harvester. I imagine they would figure out how to use it, but $20 says they’ll employ it as a weapon of war.

The point is that Pythagoreans pioneered mathematics through their use of it, even if not their application. They believed that math can grant us access to a higher truth, and in some sense they were correct.

Utilizing data in your company lets you make decisions based on what is happening in the real world, rather than on only gut feelings or intuition. For certain decisions, trusting the data is vital.

The more data you have, the more patterns you can find and the more models you can build. Amazon has used its wealth of data to understand what products are popular, profitable, and easy to produce in order to accelerate its growth past a marketplace for vendors towards being a giant outlet all of its own. It’s even leveraging that data for AI applications. From math comes life – maybe Pythagoras was right after all?

Nowadays big data is everywhere and in everything. If you’re not making use of it in your business then you’re letting your team down, you’re letting yourself down, but most importantly you’re letting the Pythagoreans down.

Aristotle reckons you should keep your feet on the ground

At the beginning of this article, I made sure to just specify that Greek thinkers are not simply Western emblems.

But if there’s any one thinker who we have really adopted and put at the heart of quote-unquote Western thought then, for me, it’s Aristotle.

Aristotle wrote on so many topics that it’s impossible for us to look at all of them.

I’m a big fan of his text Nicomachean Ethics where he lays out a great deal of his approach to moral philosophy. Not to say a modern reader would agree with it all, as 21st Century philosophical giant Bertrand Russell claims:

…almost every serious intellectual advance has had to begin with an attack on some Aristotelian doctrine.

Despite all this, Aristotle gives us some nice sentiments to take away with us.

Being a virtue ethicist, Aristotle would encourage you to be generous, courageous, sincere, modest, civil, considerate, and to act with right ambition. Through these virtues you could reach eudaimonia; a state of happiness or well-being rooted in living a life which is right for the human soul.

Which could give us the business lessons of being considerate to those you work with or employ, being ethically and morally aware as a company, working toward sustainability, and attempting to make a positive impact on your broader community.

You can read into that one however you like.

Greek philosophers were Thought Leaders before it was cool

Look, I’ll admit, this entire article is one giant stretch after another. It’s less of a philosophy seminar and more of a yoga class.

Nonetheless, the points all ring true.

And, at the next networking meet when someone asks you about your product and how it is taking shape, you can sprinkle in references to Plato and establish yourself as a Thought Leader ^TM.

But it is true that many of the debates we have today have been had for centuries or even millenia. Reading through the classics can put certain questions in perspective and highlight some small simple truths which we often take for granted.

Ultimately, what the Ancient Greeks teach us about business is that another civilization will overtake us and establish a new wave of dominance. So we may as well enjoy the ride.

Should I have included Archimedes? Who did I leave out? What business lessons would you pick up from classical texts? Let me know in the comments below!

Workflows

Workflows Projects

Projects Data Sets

Data Sets Forms

Forms Pages

Pages Automations

Automations Analytics

Analytics Apps

Apps Integrations

Integrations

Property management

Property management

Human resources

Human resources

Customer management

Customer management

Information technology

Information technology

Adam Henshall

I manage the content for Process Street and dabble in other projects inc language exchange app Idyoma on the side. Living in Sevilla in the south of Spain, my current hobby is learning Spanish! @adam_h_h on Twitter. Subscribe to my email newsletter here on Substack: Trust The Process. Or come join the conversation on Reddit at r/ProcessManagement.