It sounds like a miracle pill or silver bullet. Polyphasic sleep. How to rest for two hours a day with no ill effects.

Imagine everything you could get done with that free time! No more rushing for work deadlines, wishing you could read that book that’s been haunting your bag for a year, or trying to find time to just relax.

Unfortunately, as with most miracle solutions, polyphasic sleep has major associated health risks and little in the way of proven benefits. Most of its good press is down to urban myths and overestimating the positives.

We don’t sleep just for the hell of it – humans need solid rest to process the information gained in waking hours and properly order memories. Unfortunately, the idea of periodically napping throughout the day to replace regular sleep is consistently brought up in productivity discussions.

“An hour on the dream machine keeps me sane.” – Gustav Graves, a literal James Bond villain, talking about his sleep schedule and glowing light mask… thing

The idea is nothing if not persistent, however, and so below we’ll dive into the theory behind polyphasic sleep, the alternative sleeping schedules you can try, and what the best way to get more out of your day is.

Let’s get started.

Polyphasic sleep is a nap-focused rest schedule

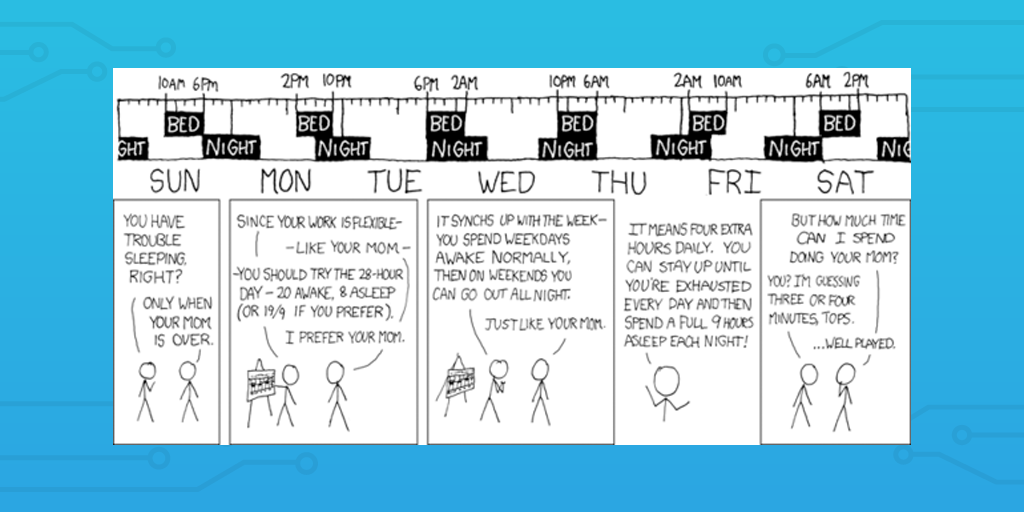

Polyphasic sleep is an alternate sleep schedule focused on getting the least amount of shut-eye as possible. The ultimate goal is to replace the regular eight-hour block of nightly rest with two hours of napping distributed evenly throughout the day.

Think of it like taking a series of power naps throughout the day and night instead of solidly sleeping. 20-minute naps every four hours (or 30-minute naps every six) are theorized to give enough rest to keep your body functioning properly while avoiding the full time sink of a solid night’s rest.

That is, of course, after sticking to the schedule for a few weeks to get over the adjustment period, during which tiredness (sometimes to the extreme) is common. Turns out it isn’t easy to reprogram your body’s natural sleeping schedule.

While it sounds a little ridiculous, the on-paper benefits of this are obvious. You’re awake for an extra six hours every day, which could be spent doing something productive.

Hell, after a week of this you’d have almost two days of extra waking time, and after a year you’d have been awake and active for 2,190 hours (91 days) more than anyone on a regular sleep schedule.

However, before you run off and plan your new sleep schedule it’s worth demystifying the lore around the practice. Polyphasic (or “Uberman”) sleep as a concept has built up a wealth of urban legends and false information over the years among those looking to maximize their productivity, to the point where even the basic health warnings are often overlooked.

First, let’s look at the three main sleep schedules humans use to get a sense of what the competing (traditional) methods are.

Monophasic and biphasic sleep are the “norm”

Monophasic sleep

Monophasic sleep is the most common schedule across the world. With the sheer amount of evidence touting the benefits of a solid eight hours of sleep every night, it’s hard to argue with the logic behind this one.

If you sleep in one block per day, you have a monophasic sleep schedule.

You get up, do whatever you have lined up for the day, then go to bed and sleep. Rinse and repeat. It’s easy to remember, and so widespread that it’s hard to imagine anyone who hasn’t at least tried this method.

While there are many tips and tricks for improving the quality of your sleep, the basic model remains largely the same and tends to fall under this classification. As such, any issues with quality of sleep using this model are a matter of environment and outside influences rather than the schedule itself.

As a quick aside, if you’re having trouble with a monophasic sleep schedule, follow these tips to get the most out of it:

- Don’t nap during the day

- Aim to get 7-8 hours every night

- Go to sleep at regular times

- Don’t use electronic devices for 30 minutes prior to sleep

- Avoid having blue lights where you sleep

- Practice meditation if your mind won’t slow down

- Get up if you can’t fall asleep after 20 minutes or so

- Try to get into a pre-sleep routine to help nod off at the desired time

Biphasic sleep

As you might’ve guessed, biphasic sleep is the method of resting for two periods during the day. While not as widespread as monophasic, it’s nonetheless commonplace in hotter climates such as Spain – if you’ve heard of taking a “siesta”, you’ve heard about biphasic sleep.

Biphasic sleep schedules usually involve sleeping one large block during the night and then taking a shorter nap at noon or in the early afternoon. While the length of the nap can vary, the total period of sleep typically adds up to around 6.5-7 hours.

For example, if you sleep for six hours at night you could have a half-hour nap at lunchtime to refresh. If your main sleep block is closer to 4.5-5 hours, the nap will probably be 1-1.5 hours long.

Hotter countries tend to see this practice more than places like the UK due to these “siestas” being a part of the culture. As mentioned above, Spanish business close for a period at noon or in the afternoon to accommodate this both to avoid the blistering midday heat and to comply with (now outdated) labor laws.

Most polyphasic sleep schedules don’t hold up to scrutiny

Now that we’ve got the three main sleep schedules outlined it’s time to compare them and examine why the “Uberman” sleep schedule isn’t everything it’s often cracked up to be. However, it’s worth noting that much of this comes down to the same kind of overzealous drive for productivity that comes with a busy lifestyle.

It’s not the polyphasic sleep can’t work. It’s more that this niche solution is not nearly as widely applicable as many would like to believe and that the associated health risks are often glossed over.

Accounts of famous practitioners are largely unsourced

“Fourteen Bizarre Sleeping Habits of Super-Successful People”. “The Secret Sauce Behind Da Vinci’s Genius (That You Can Do Too!)”. “How Churchill Worked for 91 Days More Per Year than Anyone Else”.

Those are just some of the sensationalist titles you often see when reading about polyphasic sleep. It’s easy to spin a huge benefit out of such an attractive concept, especially when the practice has been attributed to so many well-known historical figures.

To name but a few, the supposed list of polyphasic sleepers includes:

- Leonardo Da Vinci

- Thomas Jefferson

- Winston Churchill

- Albert Einstein

- Nikola Tesla

- Benjamin Franklin

- Napoleon, and many more

If this were true then it would be hard to argue with the sheer number of exceptionally productive and influential figures who all subscribed to the same sleeping pattern (many of which are also recorded as disliking the idea of sleeping as much as most others did).

The key words there being “if this were true”.

Dr. Piotr Wozniak of SuperMemo has written a beautiful and systematic assessment of each of these figures and, while I won’t go into the same detail here (this post is long enough already), he shows that it’s likely none of these figures were consistently polyphasic.

In reality, most of these famous figures suffered from insomnia and so just slept when they could/wanted to as opposed to taking up a specific napping schedule. Churchill is even known to have been a biphasic sleeper, as he slept little during the night but consistently had 1-1.5 hour naps in the afternoon.

Basically, it’s hard to find any evidence of historical figures following a set polyphasic sleep schedule (especially one which didn’t result in a later crash and extended sleep). It’s more likely that they either slept very little or had an irregular schedule.

First-hand accounts are mixed at best

Thankfully, we don’t have to rely on famous figures to know what the effects of polyphasic sleep are. With only a short Google search it’s easy to find first-hand accounts of people testing the method out and recording the results.

Unfortunately for those following the routine, these experiments are often negative or, at best, come with a hefty list of side-notes attached to their success.

Take Rudis Muiznieks for example. He tested the Uberman sleep schedule for just shy of two months after graduating college and experienced nothing but sleep deprivation and grief for his efforts.

“In hindsight, it’s pretty obvious that all I was doing was severely depriving myself of sleep and suffering all of the tortures that entails. The instant-REM naps with startlingly vivid lucid dreams are real, but none of the other touted benefits ever came close to materializing for me.” – Rudis Muiznieks, My Experience with the Uberman Sleep Schedule

Despite sticking to the napping regime as strictly as possible, Rudis suffered nothing but continually severe signs of sleep deprivation until finally giving up and sleeping for 18 hours solid.

Meanwhile, Brian Lovin had a more positive experience with his attempts with one key difference in his approach; he didn’t use the Uberman schedule. Instead, Brian took a calmer introduction to polyphasic sleep with the following schedule:

- Sleep 11pm to 2am (3 hours)

- Nap 6:30am to 6:50am (0.3 hours)

- Nap 11:30am to 11:50am (0.3 hours)

- Nap 5:30pm to 5:50pm (0.3 hours)

In six days this would have resulted in 21 extra hours of activity (Brian was previously averaging 7.5 hours of sleep) but, in practice, he managed around 12.1 due to lapses in his schedule. However, it’s worth remembering that this was only his first week of the experiment and thus still in the adjustment period.

The second week of Brian’s experiment had much the same findings – it was difficult but seemingly rewarding. He did, however, write about the social life sacrifices that come with polyphasic sleep and the dietary requirements of such a demanding energy schedule (Brian took to drinking Soylent).

However, after just half a week more he admitted both defeat and the health problems he had been having, including constant exhaustion and physical effects such as heavy dark circles under his eyes.

To sum up, it’s not looking good for those first-hand accounts we do have.

Sleep deprivation is a serious health risk

The health risks associated with attempting polyphasic sleep aren’t something to be dismissed either. While it may work for some people, humans as a whole aren’t suited to such a small amount of sleep, to the point where the negatives easily overtake any benefits.

First, let’s define “sleep deprivation”.

Depending on your age there is a set amount of sleep that you are medically recommended to get – most 18-64-year-olds require between six and ten hours of sleep every night. Sleep deprivation is the term given to someone who consistently doesn’t reach that recommended level of sleep.

This leads to a cloudy mind, trouble focusing, memory problems, a weaker immune system, and an increased risk of cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. Any of these isn’t exactly desirable in general but for someone looking to increase their productivity (by, say, decreasing the amount of time they sleep), these issues can be truly devastating.

It’s all well and good to be awake for more time every day but if that (and more) time is spent with a fuzzy mind and working at a slower pace than usual, can you really say that you’re making significant enough gains to warrant the other health risks?

“I “saved” 20 hours this week by cutting out 3.5 hours of sleep per day. Unfortunately, not all 20 of those hours were productive. Not by a long shot.” – Brian Lovin, My Polyphasic Sleep Adventure: Week 2

Best bet; try a biphasic sleep schedule

Considering the lack of evidence for a working polyphasic sleep schedule, the constant warnings that it “might not work for you” from those who tout its benefits, and the health risks associated with the practice, I’d strongly recommend against attempting it yourself.

I was originally going to recommend trying a “light” polyphasic sleep schedule (similar to the format Brain Lovin followed) but then I took a step back and asked, “what’s the point?”.

I’m not one to be defeatist before even trying but the vast amount of evidence indicating that it’s bad for your health, that humans aren’t built for such a routine, that any time gains are mired in decreased productivity, and the social sacrifices required (no going out drinking on a Friday night) make polyphasic sleep too demanding and largely pointless in its results.

However, if you’re dead set on increasing your productivity by sleeping less it may be worth trying a biphasic sleep schedule and seeing how it goes.

Key things to remember with a biphasic schedule are:

- No matter the distribution (nap vs main block), your sleep time should total at least six hours

- If you feel constantly tired, try altering when you nap (noon vs afternoon)

- Don’t oversleep, as this will ruin your sleep schedule

Before attempting this, take the time to consider what you will gain and lose by taking on such a schedule. Sure, you might get an extra hour of waking time during the day but how will you use it effectively?

Remember; if you’re consistently tired after sleeping for six hours on a biphasic schedule, you probably need to increase your overall sleep time. At this point, there’s little point in using biphasic sleep instead of monophasic unless you’re in a climate where avoiding the midday heat would be useful.

There are more consistent ways to increase productivity

I understand the drive to improve productivity all too well. Why do things in the same way when you could change your routine and get the most out of your day, right?

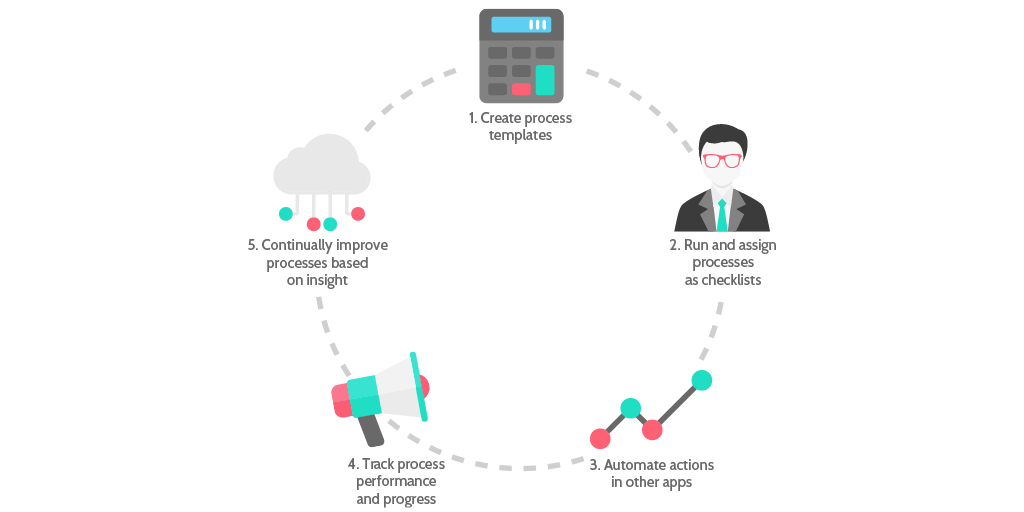

Well, there are much better ways to do that than testing the limits of sleep deprivation. Namely, through process management and by using business process automation.

Documenting workflows allows you (and anyone else following them) to perform the tasks without worrying about what to do next. There’s no hesitation or confusion, so there’s little to no wasted time. Plus, it couldn’t be easier to do with Process Street (sign up for free here!).

Not to mention that having recorded instructions to hand at all times is a great way to reduce your employee onboarding time (and strain on the team) and make sure that everything is completed correctly every time.

For the big productivity increases, however, you need to turn to process automation. This lets you link checklists and apps together to automatically take care of tasks which would otherwise take time, effort, and focus away from things that actually need your attention.

Let’s say you’re sick of having to copy customer data into your client onboarding checklists. Well, with Process Street you could set up a custom checklist run link inside your CRM to trigger a checklist and smooth the process out a little. Not only that, but that run link could push the client’s information through and automatically format it into your checklist using variables and form fields.

That’s just one of the countless ways Process Street could increase your productivity. After all, no matter how much you need to get done it really isn’t worth losing sleep over.

Do you have a unique sleep routine you’d care to share? Have you tried polyphasic schedules for better or worse? Either way, I’d love to hear from you in the comments below.

Ben Mulholland

Ben Mulholland is an Editor at Process Street, and winds down with a casual article or two on Mulholland Writing. Find him on Twitter here.