There’s a dark underbelly to process management that no one wants to talk about, but it’s time to speak out:

There are bad process management systems out there. Not just bad – these are some really nasty characters who will destroy your carefully built business from the inside out.

We have to keep this between you and me, though, because I’m not supposed to be saying any of it. Process management is a dangerous world, folks. You don’t even know. It seems all efficient and useful, increasing productivity and reducing errors – great stuff all around – but when was the last time you checked in on your innovation?

Been a while, right? Now you’re starting to put it together.

Come here, quick. I’ll run through what I know:

- Process management: What it was meant to be

- The secret truths of process management systems

- BPM adoption: Fighting the good fight

- Rosemann’s 5 stages of process management adoption

- The Process Street process management playbook

- Source List

This never happened, okay?

Process management: What it was meant to be

In the beginning, process management was just as wide-eyed and optimistic as any new system on its first implementation.

In partnership with workflow management, the two were tasked with balancing efficiency, monitoring performance, and coordinating different systems. In fact, they work so well together, that it can be difficult to tell them apart.

The core difference is that:

- Workflow management is about getting multiple people to perform individual tasks the right way at the right time

- Process management is focused on improving an organization’s processes to be more efficient

Process management also works outside the hierarchical organization model, involving multiple departments, as well as internal and external stakeholders, to implement whatever changes are needed.

And this is where process management gets led astray.

Process management, with too narrow a focus, can actually prevent redesigned processes from functioning correctly.

Can you believe it? Process management is the saboteur. That betrayal is deep.

According to David Garvin (former Harvard Business School professor), by focusing too much on improving processes, you run the risk of neglecting the ongoing management of existing processes.

For example, if an organization prioritizes improving its work processes but overlooks its administrative processes, that opens the floodgates for errors, inconsistencies, and potentially disastrous (and expensive) consequences.

For a process-centric organization, this could easily be the point of no return.

The secret truths of process management systems

The process management system comes in many guises with many names – most of them shrouded in mystery and confusion.

While there aren’t as yet any definitive interpretations of business process management (BPM), Tonia de Bruin and Gavy Doebeli narrowed down the three most common:

- Using software to manage your processes

- Following the process lifecycle for continuous management

- Managing the organization instead of just the processes

De Bruin and Doebeli are wrong.

While at first glance those three interpretations may look separate and distinct, they are, in fact, the exact same thing.

Let me explain by looking at how we do things at Process Street.

Obviously, we use software to manage our processes. We are software to manage processes, but in addition to our own platform, we use Airtable, Zapier, Atlassian, Glassdoor, and so many others.

Using software to manage your processes

We might as well have “continuous improvement” tattooed on our collective forehead as much as we stress its importance in maintaining good processes. Stagnant processes are bad processes and bad processes break.

You don’t want that.

So you have to constantly monitor, evaluate, update, and implement your processes so they operate at maximum efficiency.

Following the process lifecycle for continuous management

Focus on the process.

Literally everyone at Process Street, “History, Mission, & Values,” Employee Handbook

When the idea for this post was generated, Zapier automatically created a card in Airtable for it. Our Head of Marketing then created a blog post task and assigned it to me, where it appeared in my kanban as an upcoming task.

When the task was created, the blog post production process automatically generated a new workflow for the creation of this specific post. Simultaneously, tasks were also created for those responsible for peer review, image creation, and final editor approval – each with a link to the same workflow.

Everyone involved in the creation process was now connected, able to check the status of teammates’ progress, and aware of the work they needed to do. Through a combination of Process Street Automations, third-party integrations (like Zapier), and our SlackApp, as I progress through the workflow, each contributor is notified when their task is up and we all receive updates via Slack on how things are moving.

That is just one of the many, many processes we – and the entire company – use on a daily basis.

You could say, sure, that process only involves one department (Marketing), but it does include multiple teams within that department (writing, design, editing, leadership). More to the point, the Marketing department may be the primary user of that process, but certainly not the only department to make use of it.

That same process is used for feature announcements, interviews, customer testimonials, walkthroughs, ebooks – pretty much whatever content we come up with that needs to be made by someone.

That is what a process-centric company does: Focus on the process.

By optimizing the process, responsibility and ownership can be spread across individuals and departments. Knowledge is spread more efficiently so you aren’t reliant on a single person for vital information.

No more waiting on Gina, who’s unexpectedly out sick, to figure out what went wrong with this month’s payroll, in other words.

Managing the organization instead of just the processes

Sounds good, right? What could possibly go wrong with a system purpose-built for productivity, efficiency, and accuracy?

What, indeed.

BPM adoption: Fighting the good fight

BPM is successful if it continuously meets predetermined goals, both within a single project scope and over a longer period of time.

P. Trkman, 2010

Adoption is a serious commitment that requires a lot of forethought, planning, and evaluation. Is your business ready for that kind of change? Do you have a clear idea of what you’re getting yourself into?

Are you sure you aren’t just blinded by the neat features and feel like you need a process management system because all the other startups have one and your CEO has been asking when you will, too?

60-80% of BPM initiatives fail (Trkman, 2010). The primary reason for this is that the people implementing those initiatives don’t know what they’re doing.

That’s not their fault, though. As I’ve already said, exactly what a process management system is and how it works is pretty sketchy territory. Peter Trkman’s 2010 literature revealed that even with a decent investment in researching the concept, the outcome was vague at best.

Critical success factors (CSFs) are consistently cited as what determines the success or failure of a process management system, but – again – CSFs tend to be lumped into broad, general categories that aren’t specific to a particular business or industry.

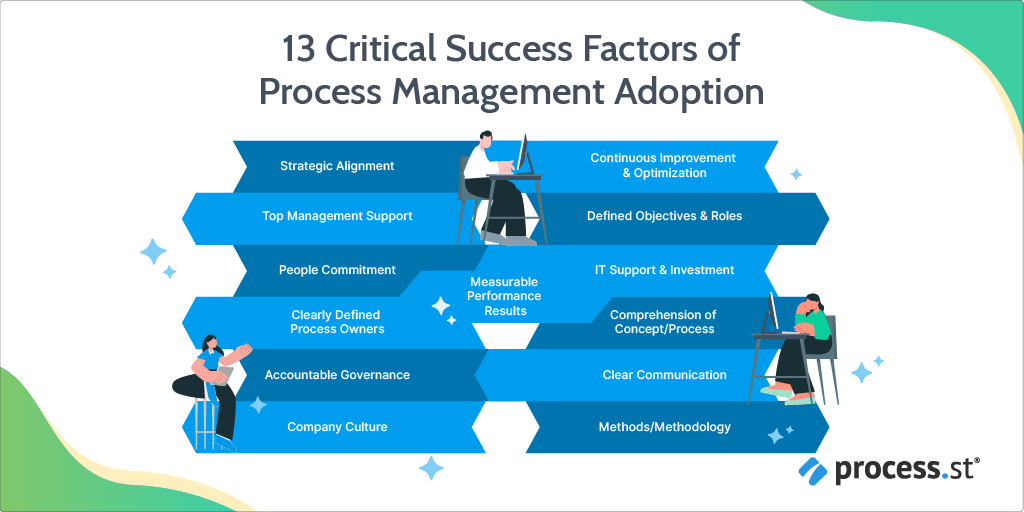

In their literature review of CSFs, Brina Buh, et al, identified 13 CSFs commonly cited as important factors in successful process management adoption:

Now, I may be oversimplifying here, but I’m willing to take a flying leap out on a limb to say all 13 of those things are critical factors to the success of pretty much everything a business does.

That is why the implementation of a process management system usually fails.

To truly succeed – and you definitely know this – you have to focus on your unique capabilities, offerings, and strengths. Winning is about standing out from the rest and showing that you have the best offer. Following any flat pack design – let alone one for your most vital processes – just isn’t going to get you there.

The tragic story of process management & innovation

We’re big on improving processes, right? We’re always looking for new ways to do things more efficiently, more effortlessly, and more enjoyably. Hey, work can be fun, okay?

A good process management system that factors in the specific CSFs for your business can have a massive impact on the success of your company.

A process management system that isn’t so attuned to your needs – or that takes too much attention from your day-to-day processes – is a supervillain in the making.

Take the blog production workflow I described earlier. It hadn’t been updated recently and the structure was starting to wear thin. To be honest, we had more “exceptions” to the workflow than standardization so it was obvious we needed to do something now.

We broke down that process step by step, considered all the different stakeholders that would be involved, which order things should be done, and what data needed to be collected during the process.

In about 20 hours, we rebuilt the whole process. Was it fine-tuned and perfect? No. Did we make it available to our team? Absolutely.

I already have a list of improvements to make based on feedback from our team, but I also have a list of other daily processes that need attention, too. I could easily go through the blog production workflow and perfect every single detail, but two things would happen:

- The other processes we use wouldn’t be maintained properly, causing them to break, productivity and efficiency to drop, and very likely my team pretty unhappy that I’ve dropped everything to focus on this singular task.

- By the time I’d perfected the workflow, it’d be irrelevant and I’d have to start over from the beginning.

In his article for MIT’s Sloan Management Review, David Garvin made this exact point about becoming too hung up on your process management. Without the right amount of perspective, he argued, ongoing processes could be neglected in favor of redesigning others.

When it comes to process improvement, this does pose a considerable risk, namely because a process can’t be improved and implemented in a vacuum. Every process is connected to another process; change one, you have to change the rest.

This is where the danger to innovation comes in. Look back at #2 above: By the time the process is perfect, it’s already out of date.

This means that – instead of creating anything new – you’re constantly playing catchup. The more time and resources you spend updating, the less you have for innovating. The less time and resources you have for innovating, the less you have for – well, everything.

Designing unique CSFs for your company prevents this from happening, but how do you determine what the right CSFs for your company are?

Buh, et al, claim it all comes down to Rosemann’s 5 stages.

Rosemann’s 5 stages of process management adoption

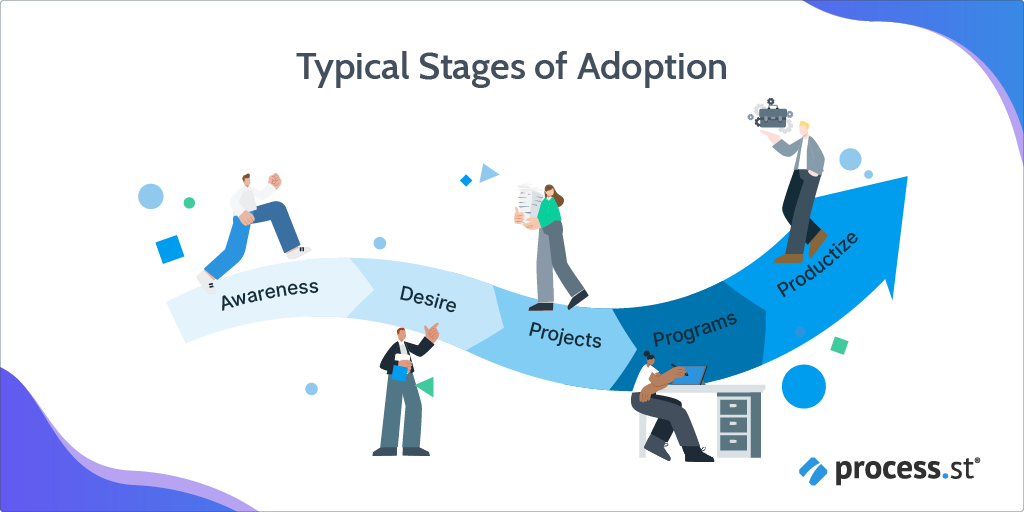

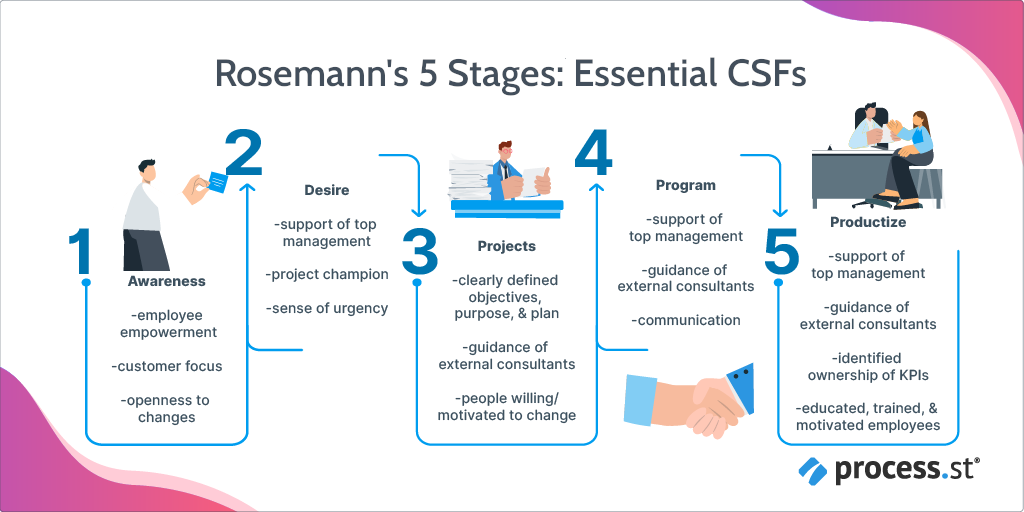

Michael Rosemann’s model breaks the adoption process into 5 distinct stages:

- Awareness

- Desire

- Projects

- Programs

- Productization

The first stage (awareness) requires the organization to recognize the value of implementing a process management system and the benefits BPM can bring to the company. Depending on the company structure, this can be a top-down movement where leadership trains employees or the employees can bring a concept or initiative to leadership.

Stage two requires a business driver and process champion to generate a desire for BPM adoption.

A driver can be any number of things; the most common reason is a need to reduce costs. Other factors might include improving management, customer satisfaction, quality management, or competitive advantage.

The process champion needs to have enough influence within the organization to persuade decision-makers that BPM adoption is something they should act on.

Once leadership has given the go-ahead, the next step is to create individual projects to build up capabilities and credibilities within the organization. You might decide to do this through training and education, process modeling, improving individual processes, or a combination of all three.

The aim of these projects is to – once successful – be converted into a BPM program where the overall methodology, strategy, and roadmap will be designed.

The final stage is all about ownership and accountability. A centralized department (or chief process officer) will be responsible for maintaining all BPM-related activities are consistent and cost-effective.

This involves the productization of business process management in order to train employees, introduce process ownership, model existing processes, etc.

That’s the theory, anyway. But what does that look like in practice?

The Process Street process management playbook

Our blog production workflow.

We all knew it needed to be updated. It was pretty hard to ignore when we’d built a workaround for nearly every task because our needs and our product had changed so much since the process was first built.

But there was always something urgent and important that needed to be dealt with right now so the most vital process that we use every day kept getting postponed to that ever-ambiguous “later.”

By the time we onboarded our newest writer (bear in mind this was seven months ago), nearly every task had a caveat attached about what needed to be done instead of following the documented process.

As a result, everyone did things a little differently depending on when they started and who’d taught them what to do. In a process that included about 90 separate tasks and involved at least four people across three departments – those little inconsistencies were a big deal.

The time and productivity lost as a result – not to mention the frustration and confusion of the team – ended up outweighing the time it would have taken to update the process in the first place.

There was no question: The old workflow needed to be thrown out.

So that’s what we did.

Stage 1: Awareness

I’ll admit it: When it comes to improving our internal processes, we have a bit of a blind spot. We’re the process experts, right? All of our processes should be perfect.

But, like anyone else, we’re just as vulnerable to falling into bad habits. We got used to our quick “fixes” that we forgot they were only meant to be temporary. That’s a slippery slope to the normalization of deviance. It’s one shortcut here, a corner cut there, and next thing you know you’re mired in broken processes.

Our stage 1 looked like this:

- We asked the team what they needed (employee empowerment)

- Built so the newest and most experienced could both use the workflow with equal efficiency (customer focus)

- Decided that “later” meant “now” (openness to changes)

Stage 2: Desire

There’s actually a lot of overlap between stage 1 and stage 2. An awareness of what needs to be done usually pushes the project champion to the forefront and that’s what gets the ball rolling.

In this case, it happened to be me, which isn’t to say the rest of the team weren’t just as eager for the improvement. I just have the sort of mind that really, really enjoys the minutiae of building a process from the ground up.

To sum up:

- Oliver (Head of Marketing) was fully onboard & collaborated with me (support)

- I blocked out time and made myself unavailable specifically to work on this (project champion)

- The longer we waited, the more broken the process would get, and it already essentially didn’t function as a usable process (sense of urgency)

Stage 3: Projects

At this stage, Oliver and I set about drafting the needs of the content team, the marketing department, and the company as a whole. We needed to create the most efficient process possible so all of the writers, designers, and editors could do their jobs quickly and effectively.

Each of us drafted an outline, which we then compared, discussed, and maybe argued a little bit over until we came up with a final draft that incorporated everything needed to create a blog post in the right order and done the correct way.

Stage 4: Program

This was the most grueling step of rebuilding the process – and the most time-consuming. Rebuilding the workflow itself took about 14 hours, with a few 3-4 hour sessions to clean up tasks, add in Automations and integrations, and set up the conditional logic parameters.

We incorporated everything our team had told us, our own experiences with the workflow, and obstacles we’d faced in the editorial process so what had once been spread over at least three separate workflows now existed seamlessly in one, with no irrelevant tasks or information to be seen.

Step 5: Productize

We presented the final(ish) version to the team, walked them through how it worked and set the whole thing in motion. In fact, they’ve been using it for over a month now and seem fairly happy with the result.

We do have a short list of improvements to make, but it’s all part of the process. By improving our blog production workflow, we can now use that experience to speed up improvements on our other workflows until it’s time to come back around and apply those tweaks and adjustments to the blog workflow again.

While the initial time and labor cost were pretty high, the long-term benefits certainly outweigh that:

- Our existing writers have a process they can trust and rely on

- Time is saved correcting inconsistencies as a result of a broken process

- Our next new writer will have a much simpler and more streamlined experience learning how to create a blog post

Which, as it happens, were the CSFs we identified for managing our process.

When was the last time you checked in on your innovation? Don’t you think it’s about time? Tell us your stories in the comments!

Source List

Buh, B., Kovačič, A. and Indihar Štemberger, M. (2015). Critical success factors for different stages of business process management adoption – a case study.

de Bruin, T. and Doebeli, G. (2010). An Organizational Approach to BPM: The Experience of an Australian Transport Provider.

Garvin, D.A. (1998). The Processes of Organization and Management.

Kirchmer, Dr. M. (2017). Successful Innovation through Business Process Management.

Palmberg, K. (2009). Exploring process management: are there any widespread models and definitions?

Rosemann, M. (2010). The service portfolio of a BPM center of excellence.

Trkman, P. (2010). The critical success factors of business process management.

van der Aalst, W. (2005). Business Process Management Demystified: A Tutorial on Models, Systems and Standards for Workflow Management.

Workflows

Workflows Projects

Projects Data Sets

Data Sets Forms

Forms Pages

Pages Automations

Automations Analytics

Analytics Apps

Apps Integrations

Integrations

Property management

Property management

Human resources

Human resources

Customer management

Customer management

Information technology

Information technology

Leks Drakos

Leks Drakos, Ph.D. is a rogue academic with a PhD from the University of Kent (Paris and Canterbury). Research interests include HR, DEIA, contemporary culture, post-apocalyptica, and monster studies. Twitter: @leksikality [he/him]