As we build businesses, we strive to make them successful in what they do and efficient in the way they carry that out.

As we build businesses, we strive to make them successful in what they do and efficient in the way they carry that out.

Six Sigma is framework with dual American and Japanese origins which helps companies achieve both of these aims.

We want to take company processes and make them better, smoother, faster, easier – it’s what Process Street does. But having a complex process optimized to the highest degree, as Six Sigma advocates, is tough.

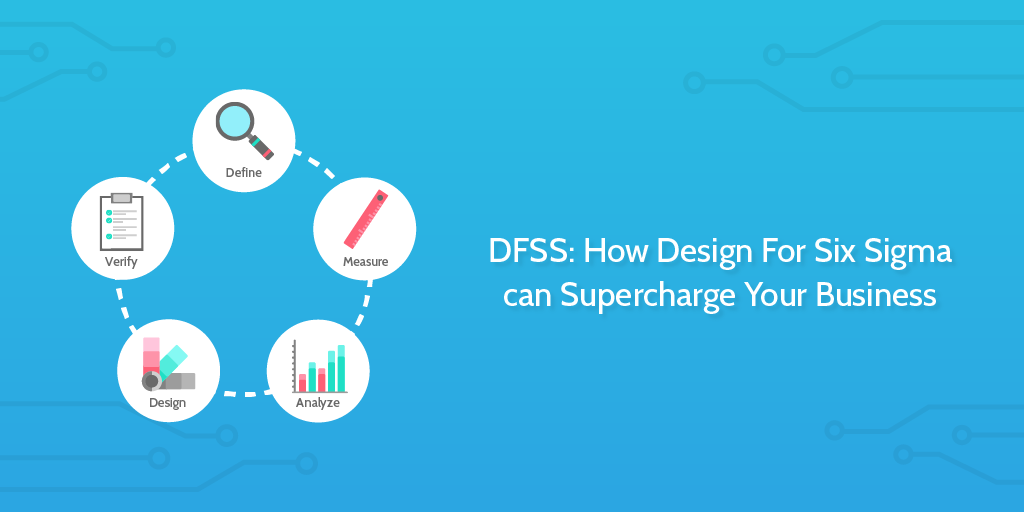

That’s why we’re going to look at Design for Six Sigma.

This will take the Six Sigma lessons and apply them to creating new processes or products. Importantly, it will help us set up these processes or products in a way which makes them ready from the start for further Six Sigma-inspired analysis.

According to Quality-One:

…[U]tilizing Design for Six Sigma methodologies, companies have reduced their time to market by 25 to 40 percent while providing a high quality product that meets the customer’s requirements.

In this article, we’ll look at:

- What is Six Sigma?

- What is Design for Six Sigma?

- What is DMADV?

- What is the difference between DMAIC and DFSS

We’ll run through the best practices of creating new products and processes in a way that they can be improved and optimized from the very beginning.

Don’t waste your time with poor processes. Start right and continue properly.

Read on to see how it works!

What is Six Sigma?

Six Sigma is an approach to process improvement which grew out of the production systems of electronics company Motorola. The engineer Bill Smith is credited with implementing Six Sigma ideas and refining its core techniques and tools during his time with the company.

The core concept behind Six Sigma is to hone a production system to reduce defects.

Defects occur all the time in various forms of production and our search for efficiency or quality is reliant on our ability to reduce the frequency of these defects.

The maturity, or effectiveness, of a production process can be measured in terms of a sigma rating. The higher the yield – lower the defects – the higher the sigma rating.

When we talk in terms of Six Sigma we’re referring to how many defects per million products occur in a production line. To achieve a Six Sigma production system you need to be defect free at least 99.99966% of the time at each defect opportunity. That means only 3.4 defective features per million defect opportunities.

Getting to a Six Sigma level is hard.

The traditional approach is referred to as the DMAIC process

What is the DMAIC process?

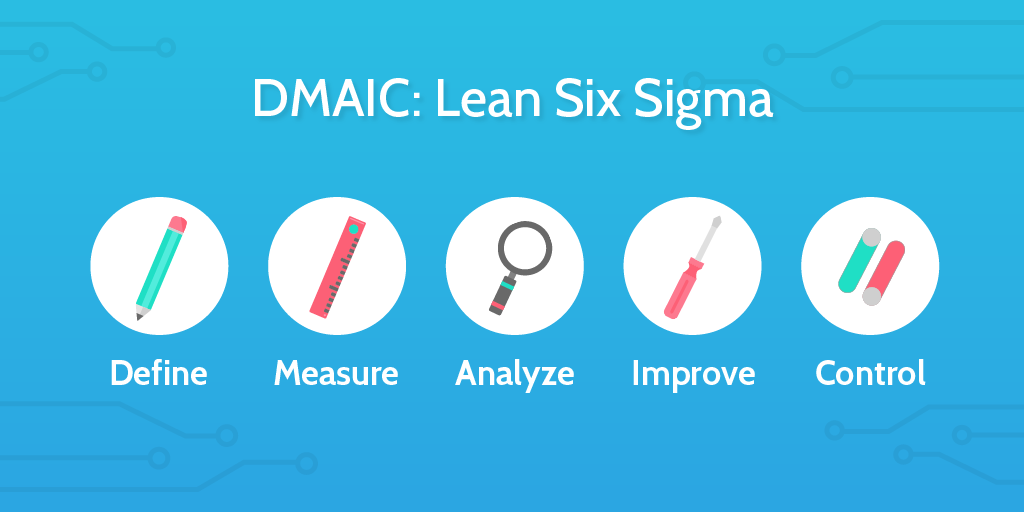

The DMAIC process stands for:

The DMAIC process stands for:

- Define

- Measure

- Analyze

- Improve

- Control

DMAIC is a data driven improvement cycle designed to be applied to business processes to find flaws or inefficiencies – particularly resulting in output defects – and to combat them. The goal of employing DMAIC is to improve, optimize, or stabilize existing processes.

The DMAIC process is everything we associate with Six Sigma. It is based on data and stats, using math to find problems within our operations in order that we can improve.

The process is a cycle in that once you finish the process, you’ll likely just start it all over again. This kind of emphasis on continual improvement shares a lot with similar methodologies and approaches like the Toyota Production System.

Most of these methodologies overlap considerably as they continue to learn from each other and iterate their own theories.

However, in the above quote you will see the final two words are “existing processes”.

So, what if we want to create a process from scratch?

What is Design for Six Sigma?

Design for Six Sigma (DFSS) is an approach which enables you to design a new process in a data driven way so that you can strive to meet Six Sigma performance. DFSS is centred around business or customer needs rather than around the performance data of existing processes.

There are two popular approaches to DFSS: DMADV and IDOV.

I apologize for all of these acronyms. They’re terrible to read and I know that.

DMADV is the process which people generally refer to when they talk about Design for Six Sigma; the two terms are sometimes used synonymously.

Yet, IDOV is a thing too. If a little less widely used.

When might I use DFSS?

To put DFSS into context, we could look at the process of designing an outbound sales process.

Now, not being a manufacturing process, it’s kind of hard to go about implementing Six Sigma into an area of business with generally high failure rates. But this is illustrative and intended to be friendly for readers outside the world of manufacturing. So cut me some slack, yeah?

Imagine we’re running a pretty decent mid-sized company and we want to launch a sales team to do outbound sales. We’ve toyed around with outbound sales enough previously to know it is an effective channel, but we don’t have set processes in place.

What do we do?

When creating a sales process in line with Six Sigma ideas, we could think about two main things:

- What does the end customer want?

- What opportunities will exist where a potential client is lost? (a defect opportunity)

Firstly, we would want to demonstrate that there is a need for this new outbound process and communicate that need to the rest of the organization. Once they’re on board, we’ll need to leverage their assistance where necessary and map our design process so they know what we think we’re going to get completed when.

Next up maybe we’ll talk to people who work in outbound sales to find out what makes a process easy for them to follow and effective in bringing the best out of their professional performance. Possibly, you might talk to some of your potential clients to try to find out what they don’t like about being contacted out of the blue. No one is against a proposal that’s mutually beneficial, but how can that be done without alienating the client.

Once you have this information you’ll likely try to bring it all together to understand key takeaways and pull out things which should be avoided in the design of the final process.

When you’ve reached the point where you’re confident you understand the needs of the design then you can start to design it. You’ll map it out, detail it, and tweak it. Perhaps you’ll run through some simulated tests of it to see whether it feels natural. You’ll then think about how you’ll record the information from the calls in a way which is actionable.

Finally, when you think you have a great outbound sales process built you can assemble a small core team and pilot the product. You might have processes like the sales processes below:

- Sales training process checklist

- Weekly sales prospecting checklist

- Cold calling checklist

- BANT sales qualification call process

- Sales presentation template

- Sales pitch planning checklist

- Closing the sale checklist

- Order processing checklist

- Monthly sales report

Once you’ve worked from the processes for a week or two you might stop and improve them to trial them again. When you’re finally happy, you start to scale your outbound team and truly integrate this new channel into your business.

Now, you’re asking what this has to do with Six Sigma.

Everything.

This is the exact same flow we will see in the DMADV process.

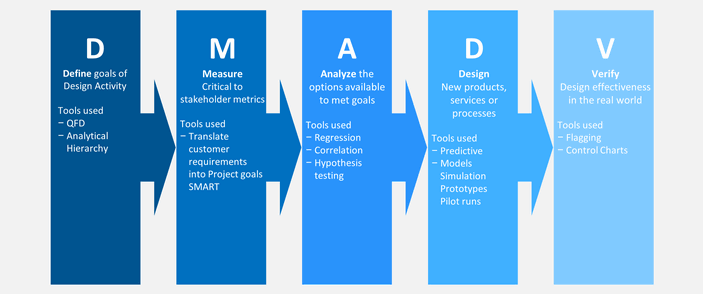

What is DMADV?

It has to be understood that DFSS isn’t a lean methodology.

In DFSS, you put in extra work and planning beforehand in order to make the first iteration of a product or process as good as it can be.

Quality One describe it as follows:

Multiple redesigns of a product are expensive and wasteful. It would be much more beneficial if the product met the actual needs and expectations of the customer, with a higher level of product quality the first time. Design for Six Sigma (DFSS) focuses on performing additional work up front to assure you fully understand the customer’s needs and expectations prior to design completion.

We advocate for lean approaches a lot at Process Street, but if you already have a solid customer base you don’t want to deliver them an MVP with all its limitations and rough edges. You want to start with quality and then iterate to a better product as time goes on.

The DMADV process is how these needs are met and how the product quality is delivered.

DMADV isn’t just about process design in the abstract, it is an organizational tool to use to assist different stakeholders within a company to come together to successfully complete the process design.

Six Sigma, after all, is not just about improving processes but improving organizations.

Define how you’re going to conduct your investigation

In this section you need to work out how you’re going to approach the challenge.

This will likely involve about 7 key considerations:

- Work out who your customer is. You need to know who you’re trying to develop this process for and why. If it’s an internal process then which team counts as your customer? If this is an external process then which actual customer is the customer in the context of this design process? Be specific.

- Develop problem and goal statements. We want to know why you’re initiating this process. What kind of pain points are being experienced to justify these efforts? How long have these pain points been felt for? Develop a goal statement which is SMART: Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant and Time Bound.

- Assemble your crack team. Define what roles are going to be had across your team for this research effort. Who is the Process Owner, the Champion, the Black Belt, or the Green Belts? And which one of you is Donatello? Your team should have experience and knowledge from across the company; a varied skill set will help when facing new or unexpected challenges. Define a communication plan for how this team will work together.

- Define your available resources. For one, do not design a production process which requires space the business doesn’t have unless there’s clear evidence that building another factory will be well worth the money. You have to work within your means. Moreover, you shouldn’t spend $1m on designing a new process if your goal is to save the company $500,000 by replacing a processes. You can do a risk assessment here too to factor in different scenarios.

- Write up your Business case. This should be a document which clearly outlines why this process design is important. Try to include these 7 points:

- Why is the project worth doing? Justify the resources necessary to engage in the project.

- Why is it important to customers?

- Why is it important to the business?

- Why is it important to employees?

- Why is it important to do it now?

- What are the consequences of not doing the project now?

- How does it fit with the operational initiatives and targets?

- Get some milestones on the board. Develop a project plan that’s well broken down with detail on timeframe, spend, and required resources/external involvement throughout the project so that you can present this as your expected performance going forward.

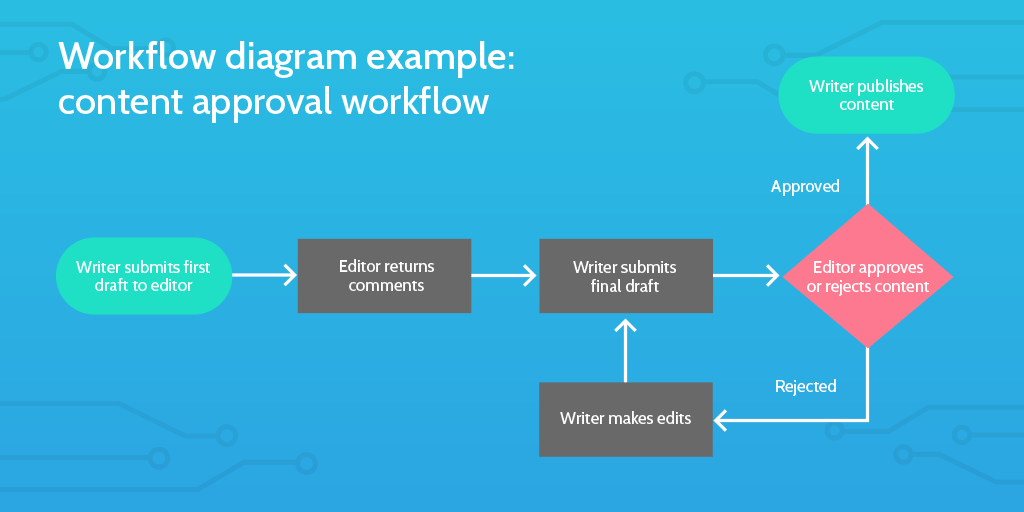

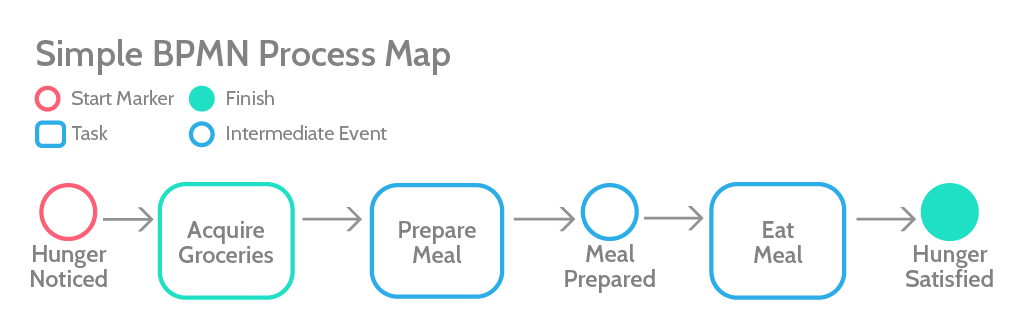

- Demonstrate how your research and design process will operate via a process map. A process map is a simple way to convey narratively the different workflows involved in conducting your experiments, research, and designs. Plus all the other things you’re going to have to do while carrying out this DFSS project. See our nice illustrative graphic below.

Measure what your customers actually want

The measuring phase is dedicated to understanding customer needs and wants.

You need to understand what elements are crucial to the customer and which are optional add ons which customers would appreciate. Quality cannot only be defined by zero defects, as Deming might comment.

If you’re designing a car, you may think that certain fundamentals of cars are the needs. Good braking, reliable, has wheels etc. But they are not the customer needs. Those are all just essential things inherent to the product. The actual customer needs and wants will likely surprise you.

In my article on the Toyota Production System concept of Genchi Genbutsu I looked at the tale of the redesign of the Toyota Sienna minivan.

Toyota launched the Sienna in the hope of entering the American market for a kind of vehicle not normally produced in Japan. The minivan seemed to have everything the customer would want on paper, but it was a disastrous flop.

As a result, Toyota gave the project to an engineer called Yuji Yokoya and asked him to reimagine the vehicle to better suit customer needs. Yokoya then did something fairly unprecedented…

Yokoya took a year off and, as reported in the Chicago Sun Times:

…drove a current Sienna more than 53,000 miles, crossing the continent from Anchorage to the Mexican border, south Florida to Southern California and all points in between.

The image below shows some of the engineering tweaks Yokoya made from his time exploring the world of the customer:

Here’s the thing though – it wasn’t just the engineering tweaks which Yokoya figured out.

He also came to a broader discovery that a minivan is not really a car for adults.

Wait, wait, hear him out…

Between 2/3 and 3/4 of the usable space in a minivan is dedicated to children. Pretty much all people who buy minivans are only buying it because they have children. The minivan is a child’s car.

The primary customer need wasn’t power steering or automatic braking or fuel efficiency or any of that.

The primary customer need was happy children.

Four key recommendations came out of this eureka moment (a phrase I really should have taken advantage of more in my last post on Greek philosophers):

- Better seat quality all through the van.

- Roll down windows for the second row.

- DVD players and entertainment centers.

- A conversation mirror so that parents could monitor the backseat.

As Yokoya said:

The parents and grandparents may own the minivan, but it’s the kids who rule it. It’s the kids who occupy the rear two-thirds of the vehicle, and are the most appreciative of their environment.

Your customer needs and wants may not be obvious. Through research and careful analysis you may be able to discover a greater truth about the market which can unleash your company’s potential.

Tools for this investigation include:

- Customer surveys

- Structured interviews

- Open format focus groups

- Historical data

- Current market trends analysis

- Immersion into customer experiences

Analyze the feedback to gather actionable data

We now have our data.

Our data is all the responses and feedback we have gathered over the course of our customer interactions and research.

Now it’s time to analyze.

This analysis isn’t the easiest as customer feedback can often exaggerate the importance of certain things over others because the customer doesn’t always know what they really want. Moreover, the research conditions can impact on how customers respond to questions.

Roger Dooley, writing for Neuroscience Marketing, describes Michael Gazzaniga’s concept of The Interpreter:

Most market researchers earn their living by asking questions – what people did, why they did it, what they might do in the future, and so on. The methodology varies – focus groups, Web surveys, interviews, etc. – but in most cases the fundamentals are similar. What would happen if these methods were applied to a person who had a diabolical module in his brain called “The Interpreter” that was constantly making up explanations for that person’s actions? These explanations would usually be logical and plausible, but in almost every case completely false. Unfortunately for market researchers, that person is all of us.

This shows that any analysis we undertake of our research must be wary of its pitfalls.

Plus, we should try to bring in elements of data which rely on what customers do as well as what they think, and be able to balance them off against each other.

You can use various approaches to help you evaluate your customer needs data in order to pull out actionable insights:

With the information gleaned from this research we can begin to put together certain design concepts. These initial concepts can be analyzed across the team and you can pull out potential positives and negatives for each.

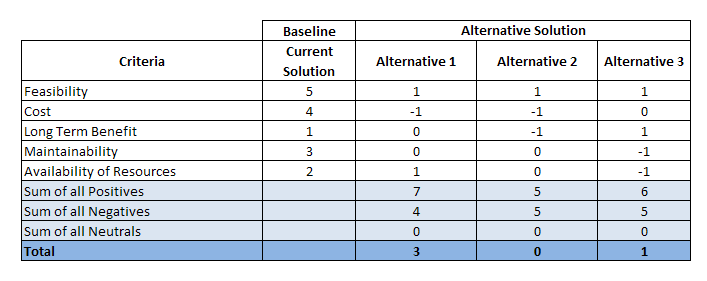

When making the final decision on which concept to carry forward into the design stage, a model like the Pugh Matrix can be a handy way to evaluate options.

In the Pugh Matrix, you select your best concept and consider it to be the base concept, or the datum, and then begin to analyze the other concepts against this datum.

The Pugh Matrix can help you weed out weaker concepts, strengthen existing concepts, and merge concepts.

Take a look at the image below first, and then read the process of how this table was constructed. As you should be able to see immediately, any alternative with a positive score in the bottom row is judged to be superior to the base concept.

What is Six Sigma lay out the process quite neatly with the follow steps:

- Construct a Pugh Matrix

- Create criteria to assess probable enhancement solutions

- Using comparative significance, allot scores for every criteria

- Determine all possible concept solution

- Weigh up how sound the potential solutions carry out on every criterion and mark scores

- Combine scores of each alternative

- Choose the best alternative with the most combined score

Fantastic! You’ve now chosen a concept. Next up…

Design your process from the concept

Depending on the kind of process or product you’re designing, you’ll use very different tools for this process.

Some may use 3D modelling to create a product, others may use just preliminary drawings.

If what you’re developing is a process, like an operational process, then you could use Business Process Model Notation to clearly convey the complexities of your construct.

BPMN is essentially an approach to process mapping that uses a universal language of symbols to add complexity to a visually simple flow. You can see an example of how this works in the image below.

If you want to learn more about BPMN and how you can utilize it in your business, check out this article:

If you want to learn more about BPMN and how you can utilize it in your business, check out this article:

BPMN Tutorial: Quick-Start Guide to Business Process Model and Notation

It goes without saying, of course, that the design for a product is inclusive of the design for how to build the product at scale. So you may use a wide variety of tools for different elements of your design; BPMN for the production flow and 3D modelling for the product and production components, for example.

Once your product is designed, you can begin to run some preliminary tests.

Two key things to do might be an FMEA analysis and a Design of Experiments. You can find a premade template embedded below which will guide you through an FMEA analysis step by step, and you can find a detailed breakdown of Design of Experiments in this article on the DMAIC process:

DMAIC: The Complete Guide to Lean Six Sigma in 5 Key Steps

Simply click I want this for my business to add this template to your Process Street account.

Once you’ve performed your analyses, you’re can pull all the results of your research together into a Design Verification Plan and Report (DVP&R).

Verify your work by creating and testing your process

The extent to which this is viable depends on what the process or product you want to create is.

A good start is to develop a prototype and run it through the necessary tests to determine to what extent it meets customer wants and needs.

As Quality One describe:

The information or data collected during the prototype or pilot run is then used to improve the design of the product or process prior to a full roll-out or product launch. When the project is complete the team ensures the process is ready to hand-off to the business leaders and current production teams.

The job of the team is to make sure to use the verification stage to make the necessary final tweaks to hone the product or process. This could involve a pilot program or a beta-launch in order to see the product in the wild and gain insights from it.

If you do choose to deploy the process in a pilot program to gather data on how it functions, you could use business intelligence tools like:

- PowerBI – comes with the Microsoft business package

- Klipfolio – good for startups or smaller businesses

- Tableau – a comprehensive enterprise friendly tool

Once that is complete a Control Plan can be developed. A control plan is like a detailed set of blueprints to bring to life everything which this research process has designed.

The control plan should outline every workflow, and why they are constructed in that way. The control plan should also give the most intricate designs for any physical items needed, like products or production machinery.

Once the control plan has been developed it can be handed off to the relevant stakeholders. Once developed, the process should aim to achieve a sigma rating of 4.5 or greater.

IDOV – A very brief outline

IDOV, which you may stumble across on your DFSS travels, has a lot of similarities to DMADV but focuses more on optimizing the process or product once it has already been designed rather than spending as much time and effort before the design process begins.

In practice, these processes can be essentially the same, depending on how they are executed. The acronym is broken down like so:

- Identify

- Design

- Optimize

- Verify

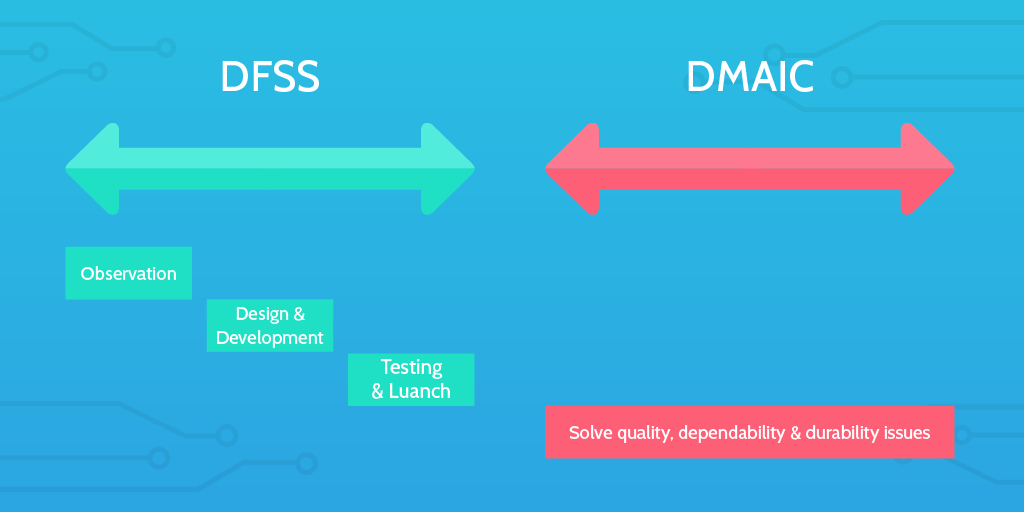

What is the difference between DMAIC and DFSS?

DFSS is best for developing new products or processes whereas DMAIC is better for improving or optimizing existing processes.

DFSS is best for developing new products or processes whereas DMAIC is better for improving or optimizing existing processes.

DFSS shares more in common with the Deming Cycle in some respects than traditional Six Sigma approaches due to greater testing and theoretical reliance on the needs of the customer. Both the Deming Cycle, understood as PDSA rather than PDCA, and DFSS rely heavily on being able to conceive of a customer’s idea of what constitutes quality.

In normal approaches to Six Sigma, quality is understood as zero defects; as that is what Six Sigma concerns itself with. Whereas in these other approaches quality is a more ephemeral and changing concept.

As Deming liked to point out, a production line could be producing products with zero defects yet the business could still be failing. People don’t buy product because they’re zero defects per million. People buy products because of their wants and needs.

As such, it’s important to recognize that DFSS lays the necessary theoretical grounding for the DMAIC process to build upon. Six Sigma requires processes like DFSS to kick off the cycle.

Have you employed Design for Six Sigma in your business? What were the challenges you faced?

Adam Henshall

I manage the content for Process Street and dabble in other projects inc language exchange app Idyoma on the side. Living in Sevilla in the south of Spain, my current hobby is learning Spanish! @adam_h_h on Twitter. Subscribe to my email newsletter here on Substack: Trust The Process. Or come join the conversation on Reddit at r/ProcessManagement.